According to Lakatos, Marxism predicted “the absolute impoverishment of the working class,” which didn’t happen. Marxists didn’t admit the mistake, kludged up some excuse, and moved on. See the previous post.

I think the story is more complicated, and it’s an example of how critical rationalists think experiments (natural or otherwise) and theories are way simpler than they actually are. As a result, their methodology (rule book) for science misleads.

I think it undeniable that the “industrial proletariat” in England or Germany are better off than in the days of the “dark satanic mills.” They’re less likely to starve, and a lot fewer children are getting mangled while using their nimble little fingers to clean industrial machinery. This is contrary to the thesis that the capitalist/haute bourgeoise class would squeeze the proletariat until the latter would have no choice but revolution.

That’s a refutation of Marxism, surely? Well, not so fast. In his Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League (1850), Marx is concerned about future attempts to “bribe the workers with a more or less disguised form of alms and to break their revolutionary strength by temporarily rendering their situation tolerable.”

I think it’s not unreasonable for a Marxist to claim that’s exactly what happened in the 20th century:

-

It’s a commonplace that the US President Franklin Roosevelt acted to “save capitalism from itself” in the 1930s. In that era, there was considerable debate about whether liberal democracy could compete with with the ascendent (supposedly more efficient) systems of fascism and communism. FDR demonstrated that it could. (He made a bold prediction that was confirmed.)

-

After World War II, it was common to worry that European countries (notably Italy and France) would tip into communism, so it can reasonably be argued that the widespread expansion of social welfare programs was Marx’s “bourgeois bribe” at scale.

So is the history of the 20th century a refutation of one part of Marxist theory or a confirmation of another? I don’t think it’s easy to tell. New predictions would be required to sharpen the question.

For example, if you believed that social welfare programs existed to placate the working classes by giving them a minimal share in the profits of capitalism, what would you predict would happen when communism became discredited as an option (with the fall of the Soviet Union)? I think you’d predict that there’d be less need to placate the workers, so the bribes would become smaller. US-centric predictions might be that (1) wealth disparities would increase…

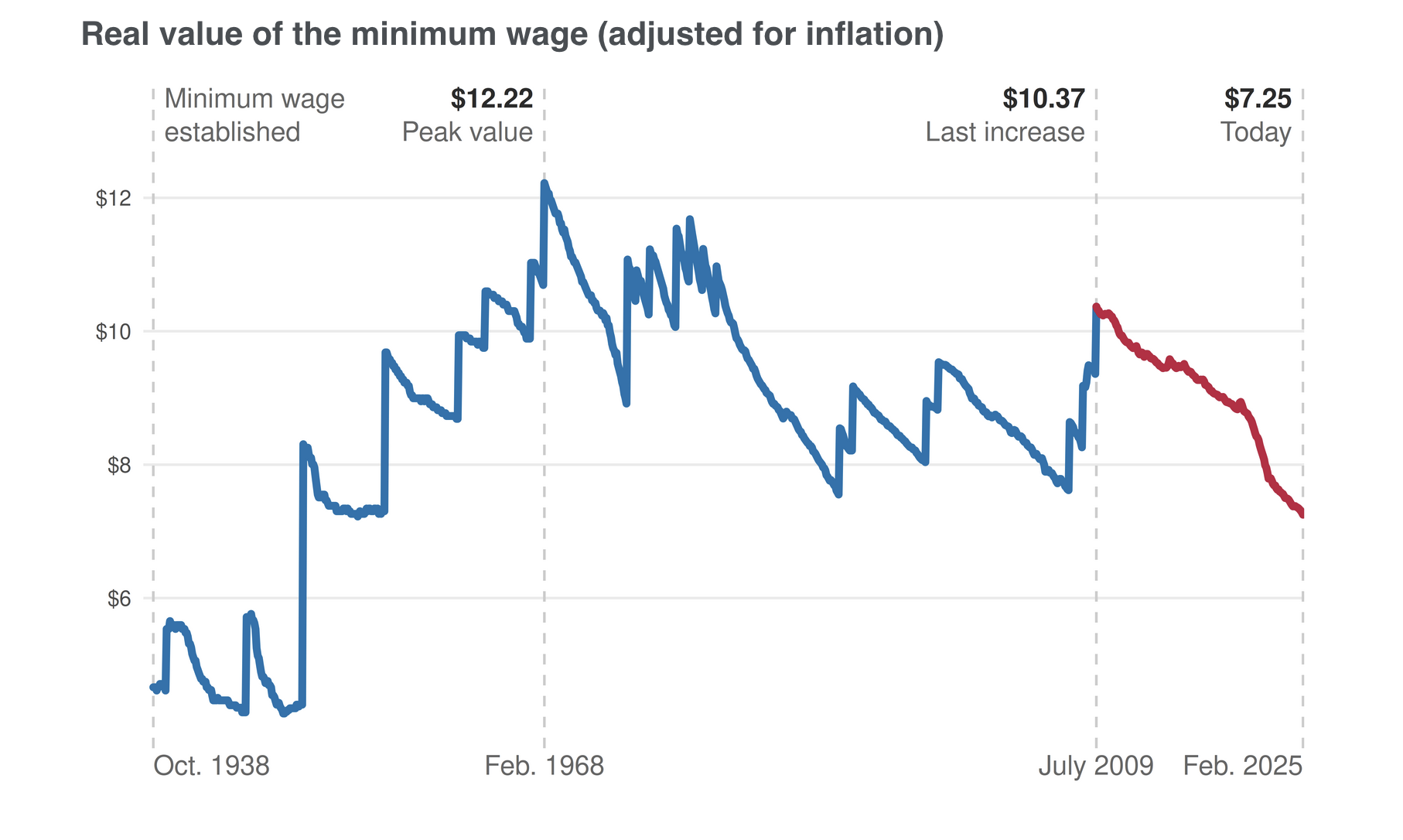

(2) increased capitalist power would lead to a stagnation in the minimum wage and a decline in its inflation-adjusted value…

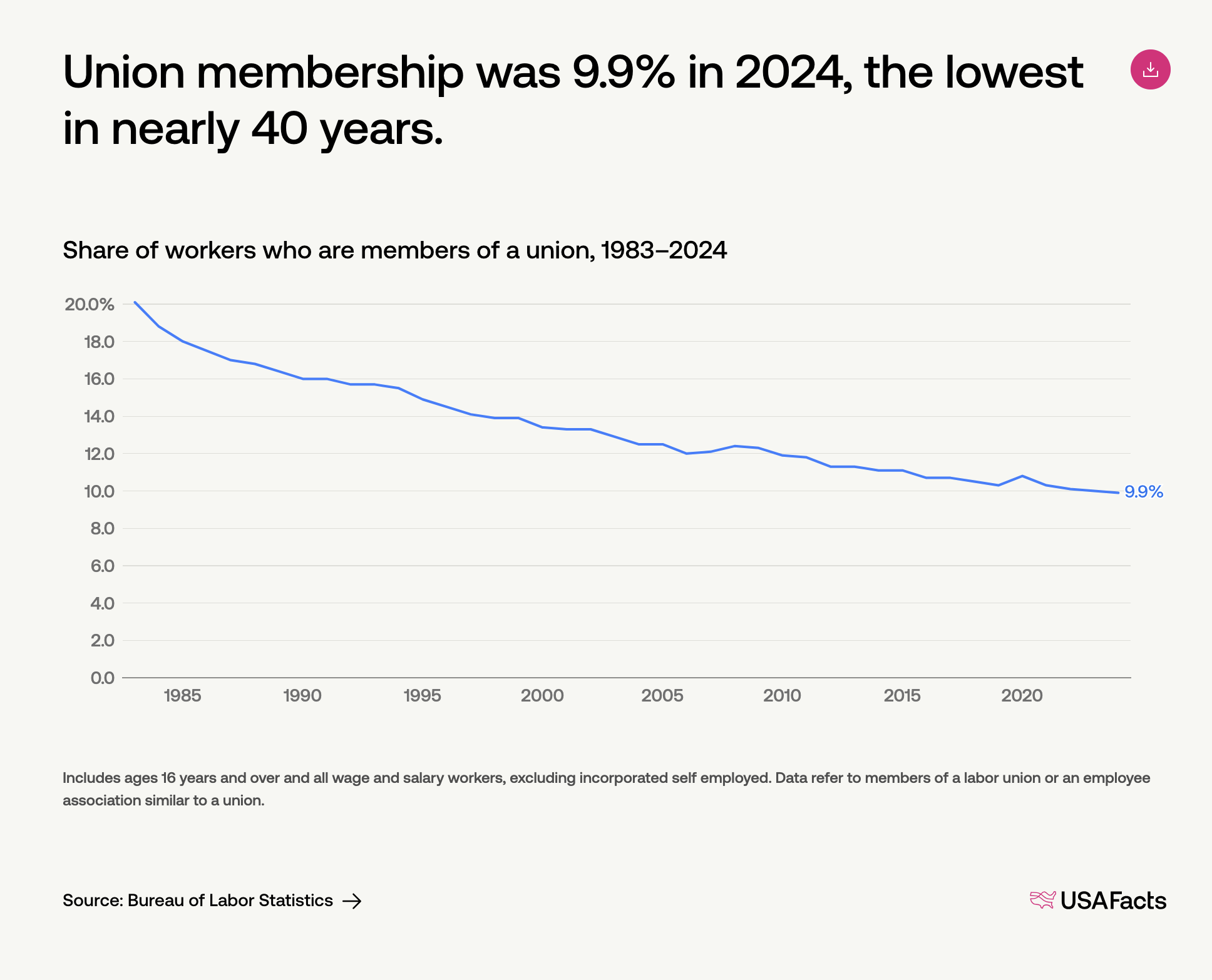

(3) union membership would decline along with worker leverage…

… and so on.

Experimentation

Let me put Marxism’s “immiseration” prediction in a more rigorous form. I’m following Lakatos’s recommendation: “The first stage of any serious criticism of a scientific theory is to reconstruct, improve, its logical deductive articulation.” Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge (1970) (full text) p. 128, followed by a particular re-articulation of a physical theory and the rather snarky comment “Physicists rarely articulate their theories sufficiently to be pinned down and caught by the critic.” I’ll return the snark by noting Lakatos’s critique of Marxist theory skips his own stage. I hope to show he would have benefited by following his own advice.

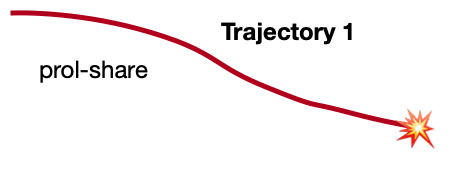

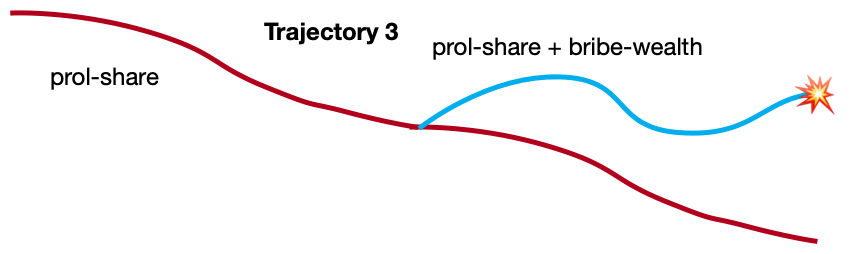

- Over time, the proletariate’s average share (

prol-share) of the nation’s absolute (not relative) wealth will decline. Plot it, and the line will persistently go down. - “Persistently go down” should be interpreted to allow for random fluctuations. Some years, there’s a bumper harvest of crops and the price of food goes down, so the

prol-sharewill increase. That temporary bump shouldn’t count as a falsification. A plot ofprol-shareshould use some sort of smoothing, a rolling average. - The end result of the persistent decline will be revolution.

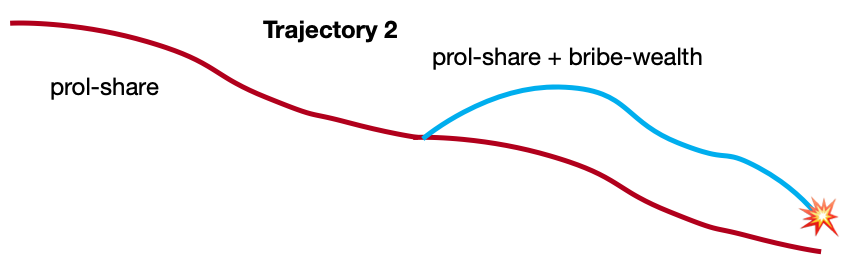

- Between the starting point of the experiment and the revolution, the bourgeoisie may “bribe” the proletariate to stave off the inevitable. Although many of the bribes – the right to unionize, for example – will only be indirectly tied to wealth, model them all as direct transfers (

bribe-wealth). Then the graph ofprol-share+bribe-wealthmay have periods of longer-than-random stability or even increase, but this total at the moment of revolution will be less than the startingprol-wealth.

If I’m right in this formulation, this would be one possible observation of the inevitable course of history:

In this case, the bourgeoisie doesn’t bother bribing the proletariat, so things descend smoothly to revolution, as predicted.

But the following observation would also count as a confirmation of the theory:

Here, the bourgeoisie bribes the proletariat, but (inevitably) the dynamics of the capitalist mode of protection will undo the bribe, leading to an eventual decline to the revolutionary point.

But the following would falsify the theory, as the revolution happened with the proletariat less immiserated than they had been in the past:

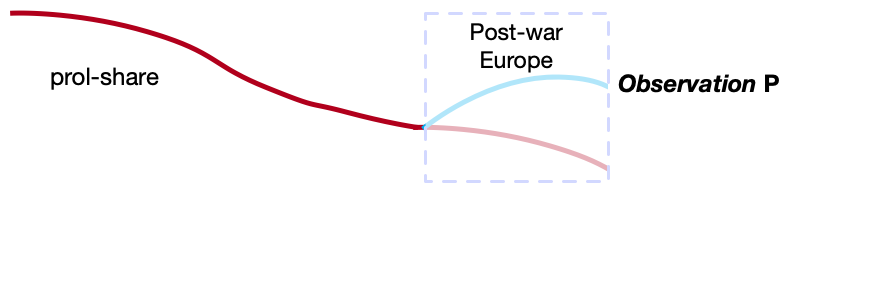

The important thing is that you can’t distinguish between the latter two trajectories until the revolution. Popper was making the following observation to test the theory:

That is, his observation comes before the revolution (if any), and the data he has don’t suffice to distinguish between the confirming trajectory 2 and the falsifying trajectory 3.

By analogy, suppose a physicist predicts that all supernovae happen in stars of type X. You can’t judge the prediction for a particular star before it explodes.

In his The Open Society and its Enemies (1945), Popper asserts that the “development of mixed economies and welfare states in liberal democracies” falsified the Marxist prediction because such societies have “trade unions, legal protections, and political intervention.“ Quotes from the “Marx’s Prophecy” section of the Wikipedia article on Popper’s The Open Society, volume 2 (“Hegel, Marx, and the Aftermath”) rather than from Popper himself. I haven’t read the book, so I can’t pluck out direct quotes.

But this is asserting that the trajectory seen since WWII will continue ad infinitum. He is (whisper it) committing the sort of induction that his critical rationalism explicitly rules out. How is saying that a number of good years ensures all following years will be good any different than saying a number of white swans ensures all swans are white? You may say that the number of years without a revolution increases the chance the prediction is false, but – provided I understand Popper correctly – that’s not a move he allows himself.

That’s a logical error, yes, but I claim it’s based on a fundamental flaw in the methodology of critical rationalism: its proponents act as if experiments are easy. But they’re just not, especially on the cutting edge. Results are frequently ambiguous, and not just because the observable event hasn’t happened yet.

The book to read on this seems to be Peter Galison’s How Experiments End (1987), which I’m embarrassed to say I haven’t read. I have read his later Image and Logic: A Material Culture of Microphysics, 1997, which covers some of the same themes. Here’s a quote:

Textbooks do not tell you that groups of physicists gather around the table at CERN stamping OUT and IN on event candidates. This may be due to the persistent myth that, at least at the level of data-taking, no human intervention ought to occur in an experiment or, if it does occur, that any selection criteria should conform to rules fully specified in advance. But here, as everywhere in the scientific process, procedures are neither rule-governed nor arbitrary. This false dichotomy between rigidity and anarchy is as inapplicable to the sorting of data as it is to every other problem-solving activity. Is it so surprising that data-taking requires as much judgment as the correct application of laws or the design of apparatus? [My emphasis]

As if writing to Popper directly, Galison also claims:

In denying the old Reichenbachian division between capricious discovery and rule-governed justification, our task is neither to produce rational rules for discovery—a favorite philosophical pastime—nor to reduce the arguments of physics to surface waves over the ocean of professional interests. The task at hand is to capture the building up of a persuasive argument about the world around us, even in the absence of the logician’s certainty. [My emphasis]

By insisting on an unbridgeable gulf between “mob psychology"

Lakatos’s term, but the sentiment is common among critical rationalists. In his “Response to my critics,” Kuhn writes “My critics respond to my views on this subject with charges of irrationality, relativism, and the defence of mob rule. These are all labels which I categorically reject […]” (Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge, p. 235) and rule-based science, the critical rationalists ignore how much of even the science they love best (physics) occupies that forbidden zone.

Both Lakatos and Popper write little (that I’ve seen) about an essential activity of science: statistical analysis. Even in their lifetimes, results like p=0.03 and R²=0.14 were important to science. Galison’s Image and Logic describes how particle physicists gradually shifted from “image” (pictures of particle tracks and the like) to “logic” (counting and statistics). It seems to me that the critical rationalists got stuck thinking that all experimental observations are as easy as looking at a particle track in a bubble chamber, when they were even in their time becoming a vastly statistical affair. Lakatos is fond of putting ‘statistical techniques’ in scare quotes: “[…] adjustments may, with the help of

so-called ‘statistical techniques’, make some ‘novel’ predictions and may […]”

Criticism, p. 176 (my emphasis)

Moreover, experimental results don’t matter much. At its core, an experiment reveals one bit of information: Does the experimenter believe a prediction has failed? True or false? 1 or 0? I refer to the experimenter’s belief instead of using words like “confirmation” or “falsification” because the theorist has leeway to interpret the results. It is always logically possible to argue that the experiment is at fault rather than the theory, though Popper and Lakatos treat such cases differently.

For Popper, the process proceeds recursively. A logical claim about the experiment may be countered by a claim about the claim, which could lead to a claim about the claim about the claim. Popper allows the recursion to bottom out at “basic statements” – “simple descriptive statements, describing easily observable states of physical bodies”. Karl Popper, Conjectures and Refutations: the Growth of Scientific Knowledge (5/e)), 1989, p. 267 (Note the assumption that such simple observations are always available.) He allows the community of scientists to collectively decide that such basic statements are to be treated as true without further argument.

For Lakatos, scientists are always free to ignore anomalies if they choose. (However, if a theory persistently ignores all anomalies and also fails to be elaborated to create new predictions that are sometimes confirmed, scientists are rational to abandon it as going nowhere. Notice that Lakatos allows that what he calls a “degenerating” research programm may revive. That means the scientist is presented with a problem parallel to judging the immiseration of the proletariat. See the Lakatos entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy for an example. Search for “Flynn effect”.)

They both agree that an adjudicated falsification provides little to the theorist. Popper views theories as sets of universal statements. Falsifications and confirmations are useful because they allow us to “be reasonably successful in attributing our refutations to definite portions of the theoretical maze.“ Conjectures and Refutations, p. 243 Once that’s done, the theorist finds the fix by using his own genius and the internal logic of the theory, what Lakatos calls its positive heuristic: Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge, p. 135

The positive heuristic of the programme saves the scientist from becoming confused by the ocean of anomalies. The positive heuristic sets out a programme which lists a chain of ever more complicated models simulating reality: the scientist’s attention is riveted on building his models following instructions which are laid down in the positive part of his programme. He ignores the actual counterexamples, the available ‘data’. [The emphasis and scare quotes are in the original.]

That last sentence is quite striking. Elsewhere in Lakatos’s paper, he uses Newton’s gravitation (pp. 135-37) and “the Bohr atom” (pp. 138-54) as examples of the “relative autonomy of theoretical science” [his emphasis]: Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge, p. 137.

Which problems scientists working in powerful research programmes rationally choose, is determined by the positive heuristic of the programme rather than by psychologically worrying (or technologically urgent) anomalies. The anomalies are listed but shoved aside in the hope that they will turn, in due course, into corroborations of the programme. Only those scientists have to rivet their attention on anomalies who are either engaged in trial-and-error exercises or who work in a degenerating phase of a research programme when the positive heuristic ran out of steam.

We’ve come a long way from the observation that you can’t move from a set of examples to a universal statement (the problem of induction). The great scientists don’t actually need examples at all. In 1885, the Swiss experimenter Johann Jakob Balmer unveiled the empirical Balmer series of lines in the spectra of the hydrogen atom. Conventional histories present the Balmer series as something theorists needed to explain. Lakatos disagrees: Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge, p. 147

But the progress of science would hardly have been delayed had we lacked the laudable trials and errors of the ingenious Swiss school-teacher: the speculative mainline of science, carried forward by the bold speculations of Planck, Rutherford, Einstein and Bohr would have produced Balmer’s results deductively, as test-statements of their theories, without Balmer’s so-called ‘pioneering’. [Scare quotes his, as is the dismissive “ingenious Swiss school-teacher” – Balmer had a PhD in mathematics.]

… and: Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge, p. 187

The direction of science is determined primarily by human creative imagination and not by the universe of facts which surrounds us.

Kuhn, as a historian rather than a philosopher, was aghast: Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge, p. 246

Lakatos’s attempt to reduce science to mathematics, leaving no significant role to experiment, goes vastly too far. He could not, for example, be more mistaken about the irrelevance of the Balmer formula to the development of Bohr’s atom model.

… and devotes pages 256-259 of his response to contradicting Lakatos on the history.

Perhaps it’s just that I’m married to an experimentalist, but I’m with Kuhn. The degree to which critical rationalists disparage, downplay, and ignore what Kuhn called “normal science” and John Watkins called “hack science" Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge, p. 27 seems wildly disproportionate. I simply don’t believe successful science treats observations as occasionally-useful hints, nor do I think any methodology built on that can actually explain science’s successes. I think Hacking’s entity realism is much more plausible.

I think this attitude accounts for the apparent failure of either Popper or Lakatos to investigate the details of the history of the industrial revolution up to their present to determine how and to what extent it deviated from Marx’s predictions. You only need one bit of information, so how hard do you need to look to decide if that bit is 1 or 0?

I was surprised to realize that the critical rationalists, usually counted on the realism side of the Science Wars are actually close to the “social constructivist” faction, except that they point to logic and inspiration as the source of our descriptions of reality rather than sociology. For a highly opinionated history of the Science Wars from a realist perspective, see William Gillis, Did the Science Wars Take Place? The Political and Ethical Stakes of Radical Realism, 2025. For a “can’t we all just get along?” account, see Ian Hacking, The Social Construction of What?, 2000. You could argue that the Science Wars were sparked by Bruno Latour, Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts, 1979. It’s a good read.

I suspect that working scientists, even pure theorists, are wise not to be so dismissive of experimental results.

Which theories and theorists count?

Let’s suppose that Popper and Lakatos never knew of Marx’s “bribe” prediction. They were both steeped in Marxism-Lenism in their youth, but maybe they never read “Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League,” and maybe Marx never mentioned that idea elsewhere.

And leave aside their problem with prejudging the evidence before the revolution.

There’s another problem in their use of their approach. Consider this story of correct methodological behavior:

-

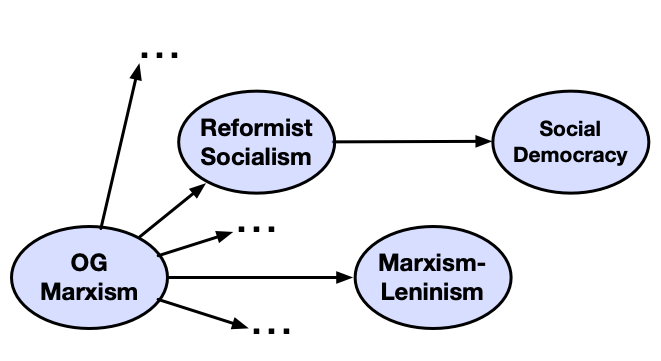

Marx founded a Lakatosian research programme (although earlier socialists who influenced Marx might have something to say about that).

-

Both Lakatos and Popper say theories evolve over time, sometimes in response to refutations, other times because of their own internal logic. Moreover, both allow multiple theories to be “in play” at the same time.

-

So it’s entirely possible for variant theories to “fork off” from the mainstream development of Marxism. And it happened: Marx himself spent a lot of time warring with people who were Deliberately and Annoyingly Not Getting It. See the Origin Story podcast episode on “Karl Marx: the Fighter”

-

One such successor theory was social democracy which, over time, “went from a ‘Marxist revolutionary’ doctrine into a form of ‘moderate parliamentary socialism’.“ Wikipedia text, citing to Ian Adams, Political Ideology Today (2/e), 2001, p. 108. They ceased to predict proletarian revolution because the Marxian bribe could be extended forever.

-

In other words, their theory predicted “development of mixed economies and welfare states in liberal democracies” – just as Popper said had happened in the West (in large part because the social democrats, pushed by their theories, formed political parties to make it happen).

-

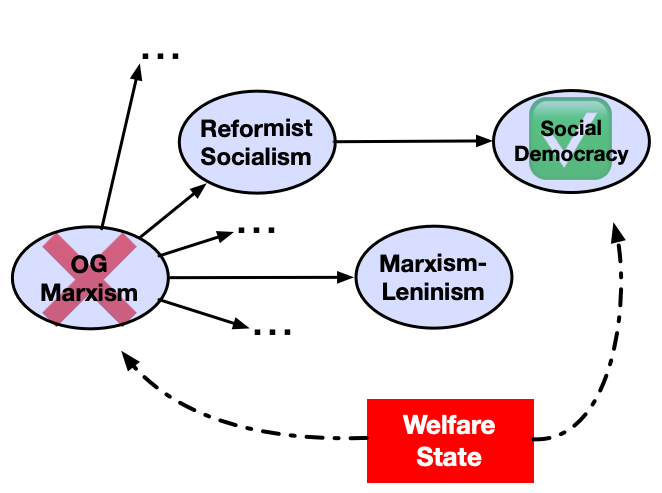

Therefore, what the critical rationalists present as a falsification of a predecessor theory is actually a confirmation of a successor theory.

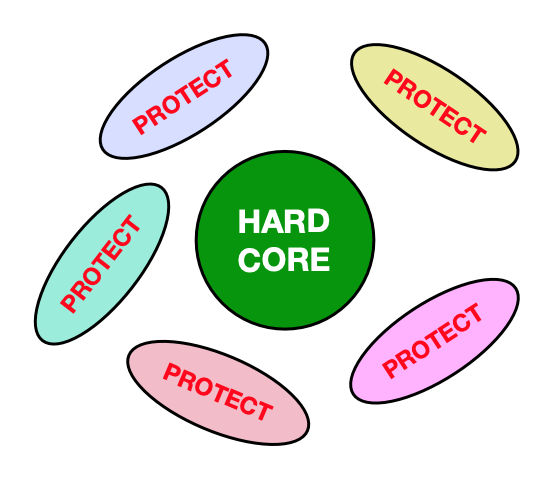

Visually, here’s a family tree of Marxist theories:

A single observation has two different effects on two different theories:

This should be entirely normal: a newer theory should by definition have “greater empirical content” than an older one. Yet our critical rationalists don’t point to this as an example of what Lakatos would call a progressive research programme. Instead: they say Marxism (seemingly the whole tree of theories) is degenerating. What’s going on?

As I said in the last post, I’m bowing to the critical rationalists by not attributing their errors to their horrible experiences with Marxism-Leninism. Instead, I promised to use them to identify flaws in the methodology. I see two.

Critical rationalists act on the Great Man theory of science.

In their writing, science works because of individuals like Galileo, Newton, Einstein, Bohr, and other people named in popular histories of science. While there are many scientists who are not great, their careers are somewhere between uninteresting and pitiable. Watkins discounts Kuhn’s “normal science,” writing “methodology, as I understand it, is concerned with science at its best, or with science as it should be conducted, rather than with hack science.” (Conjectures and Refutations, p. 27) Popper: " In my view the ‘normal’ scientist, as Kuhn describes him, is a person one ought to be sorry for. […] [He] has been badly taught. He has been taught in a dogmatic spirit: he is a victim of indoctrination. […] As a consequence, he has become what may be called an applied scientist, in contradistinction to what I should call a pure scientist. (p. 52-3, italics in original.)

The case histories of the critical rationalists tend to be biographical. Newtonian physics is the story of Newton. Predecessor characters like Robert Hooke (who suggested to Newton that he break orbital motion into a straight-line tangent to the orbit and a radial motion toward the focus) are skipped, as are the contributions of later people to the theory. To me the histories read: There was Newton, who thought a bunch of amazing thoughts. Then there were a few big deal (“crucial”) experiments. Then not much happened for 200-some years. Then came Einstein.

Crucially, this focuses their analysis on the beginnings of research programmes, and away from the various elaborations and corrections. As a result, falsifying Marx – at the root of a tree of theories – is taken to falsify all the theories that followed.

Critical rationalists focus on subsets of theories.

Theories are sets of universal statements, but not all universal statements are the same. There are subcategories. Here’s the first.

Lakatos describes the founding theory of a research programme: For and Against Method: Including Lakatos’s Lectures on Scientific Method and the Lakatos-Feyerabend Correspondence, Motterlini (ed.), 1999, p.103

At the heart of any research programme is a “hard core” of two, three, four or maximum five postulates. Consider Newton’s theory: its hard core is made up of three laws of dynamics plus his law of gravitation.

Popper describes the creation of a completely new theory (he doesn’t much use the phrase “research programme”): Conjectures and Refutations, p. 241

The new theory should proceed from some simple, new, and powerful unifying idea about some connection or relation (such as gravitational attraction) between hitherto unconnected things (such as planets and apples) or facts (such as inertial and gravitational mass) or new ‘theoretical entities’ (such as fields and particles). [his emphasis]

Theories grow by creating what Lakatos calls a protective belt of other universal statements or hypotheses:

The hypotheses accrete over time. They might be pure additions, or they might demand modifications to existing statements in the protective belt. But there won’t be changes to the hard core. Popper doesn’t specifically rule out changes to the hard core – he describes changes in even vaguer terms than Lakatos does – but I suspect it’s true. He implies – or I infer – that the need to do that would trigger the creation of a replacement powerful, simple, new, etc. theory – basically, starting over.

One type of protection is the purely defensive ad hoc hypothesis: one that explains away a falsification but doesn’t make any new, testable predictions. For Popper, that’s an immediate red flag: We USAnians never miss an opportunity to make a fußball metaphor. you’ve stopped being scientific. For Lakatos, it’s a yellow flag: if you keep doing it, the research programme will be seen as degenerating and scientists will rationally abandon it.

The other type of protection adds to the growth of knowledge by both protecting from an accepted falsification and also making new (preferably bold or unlikely) predictions (that, for the programme to stay progressive, must at least occasionally be confirmed).

Because the critical rationalists aren’t specific enough, I don’t know what else goes in the belt. For example, a theory of the pendulum is a logical consequence of Newton’s gravitation. And it’s been amply confirmed. Does its equation of motion go in the protective belt – protection from what? – or does it go somewhere else? It’s got to go somewhere, right?

My point? Critical rationalism focuses on the hard core and marks the rest as uninteresting. Perhaps it’s a matter only for those badly-trained applied scientists, not for the Great Man of Science or the later Great Men who will seek to explain his greatness. (Maybe that’s too snarky. Oh well.)

If you consider the immiseration of the proletariat to be part of the hard core of Marxism (or a prediction deductively derived from the hard core) and you want to evaluate whether the whole Marxist programme is a science or a pseudoscience, you’d naturally look to the original hard core, not to mushier derivative theories that make predictions that are less bold. After all, the social democrats were predicting a future much like the past, except getting better via the slow boring of hard boards.

And critical rationalists prefer to sing of warriors fighting dragons than of farmers fighting weeds, year after year.