Given my goal for this series, I knew I’d have to explain more about the rules Karl Popper and Imre Lakatos think scientists should follow to be worthy of the name. Rather than smear the content throughout other posts, I’ve decided to put it all – well, most – in one place.

I’ve organized the post around the kind of running example I’ve wished my authors had given. They concentrate so much on justifying their rules that they explain them only in bits and pieces, not as a coherent whole.

This is a toy example, but I think it’s still useful.

Background

Popper and Lakatos devoted big parts of their careers to the so-called “demarcation problem": how can one distinguish science from pseudoscience? They each proposed sets of rules to characterize proper science. They call those sets of rules “methodologies.”

Popper’s methodology is called “critical rationalism,” and it’s close to the “scientific method” as taught in school.

Lakatos started out as an acolyte of Popper’s who came to see himself as extending and correcting Popper’s methodology. (Popper did not agree, to put it mildly.) Lakatos called his version “the methodology of scientific research programmes.”

I think their attitudes, assumptions, and rules are close enough that I’m going to call them both “critical rationalists” and use “critical rationalism” as the umbrella term. My explanation will use Popper’s version as its base, with Lakatos’s ideas presented as elaborations.

In what follows, highlighted words mark the first use of an important concept that I’ll use in later posts, but I also highlight for emphasis. Sorry about the ambiguity.

Sources, described

The entries on Karl Popper and Imre Lakatos at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy are good.

Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge, Lakatos & Musgrave (eds.), 1970. (full text). This is a collection of papers capturing discussion at a 1965 symposium where critical rationalists beat up on Thomas Kuhn for his The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), ending with his somewhat bemused response. The Lakatos paper stands out as a solid description of his methodology. Paul Feyerabend’s paper stands out because it was a defense of Kuhn that I imagine had Kuhn thinking, “Paul, I appreciate the good intentions, but you. are. not. helping.” The Popper paper I thought was useful because it states bluntly things I realized had only been implied.

For and Against Method: Including Lakatos’s Lectures on Scientific Method and the Lakatos-Feyerabend Correspondence, Motterlini (ed.), 1999. The transcripts of Lakatos’s lectures are good, concise, though often snarky explanations of both his and Popper’s ideas. (They are from after Popper repudiated Lakatos – in 1970 – and it shows.) The correspondence is a washout because Lakatos carefully filed away Feyerabend’s letters (typical) but Feyerabend used Lakatos’s letters as bookmarks and such (also typical), so not many survived. Feyerabend’s letters are long on gossip and low on ideas.

Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge (5/e), Karl Popper, 1989, is a collection of essays. I relied on the “Truth, Rationality, and the Growth of Knowledge” chapter, plus pages the index took me to. If you were to say I should have read the whole thing, I wouldn’t argue with you. Or reread. I bought it during my “it’s sinful to highlight books” phase, so I don’t know how much I actually read.

My example

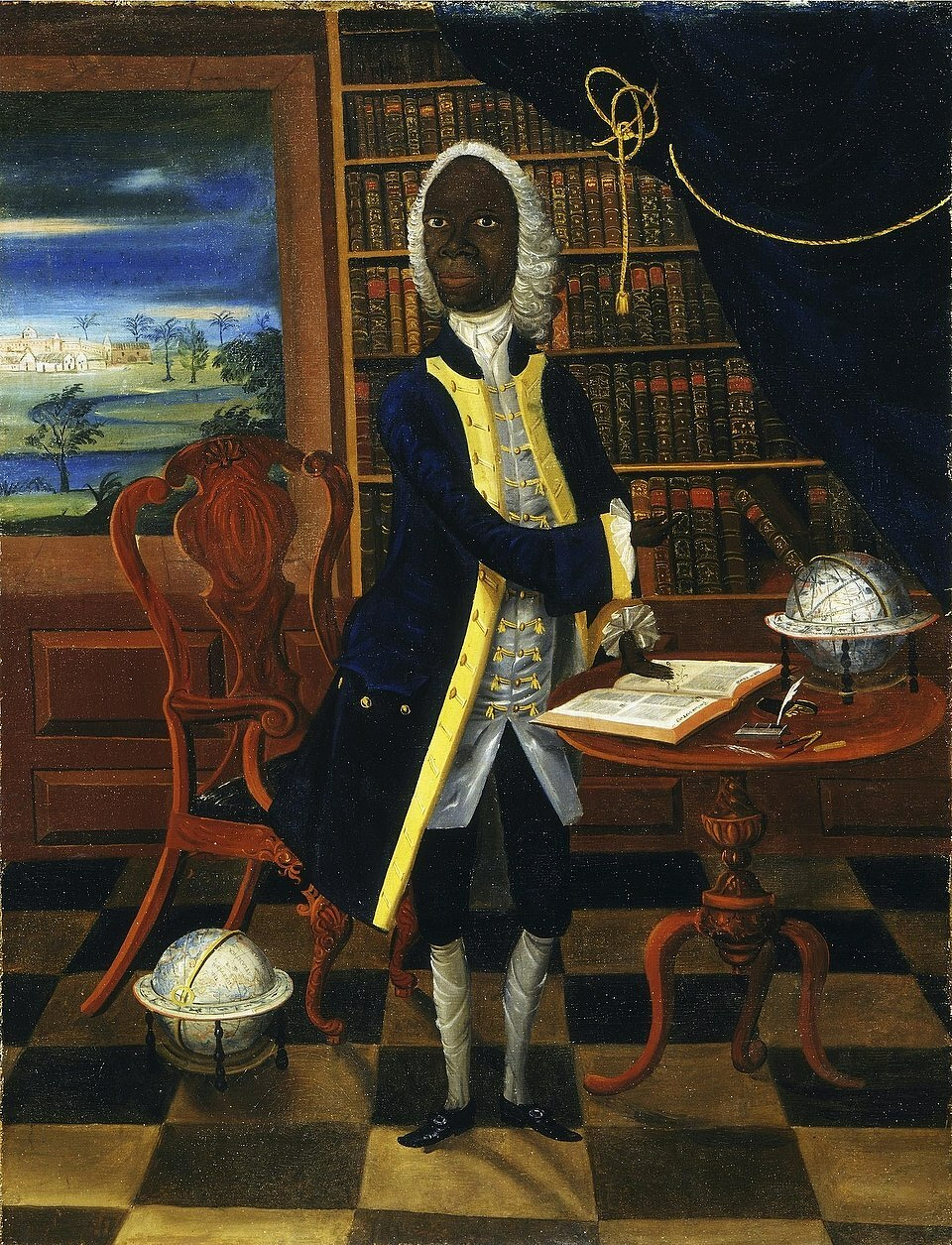

Francis Williams (c. 1690 – c. 1770) was a Jamaican polymath. He’s most known for astronomy. But let’s assume that, like so many “natural philosophers,” he was also passionate about collecting and studying particular animals. In this case, birds. Specifically, swans.

And let’s suppose that, because he’d seen a lot of swans, he put forward a universal truth-valued claim:

Claim WhiteSwan:

- All swans are white.

Critical rationalists would call this a theory, as it’s a collection (of size one) of universal claims.

Time passes. Williams receives a crate from Australia. In it, there are several odd animals, including what looks for all the world like a swan – except its feathers are black. What now of his universal statement?

He could change it to this:

Claim ExceptThisOne:

- All swans are white.

- Except for this one right here.

That’s obviously silly, but why? A critical rationalist would say:

-

A theory’s supposed to make predictions about the world. In the case of the

WhiteSwantheory, that prediction is: “no matter where you look, you will never find a non-white swan.” -

But

ExceptThisOnemakes the same prediction! No one will ever find a non-white swan, because the only one is already accounted for. -

Equivalently,

ExceptThisOnegives no hint about what anyone searching for swan specimens should do differently.

The rule is that you shouldn’t change or extend a theory unless the new version makes new predictions about the world. Anything else is an ad hoc change that was most likely made to protect the original theory against an inconvenient fact. It marks you as doing pseudoscience, not science. Explaining away, not explaining.

𓅮𓅮𓅮

Williams might also have had reasons to “contest the carcass.” It happens that the cover letter attached to the crate describes the specimen only as “a peculiar Antipodean swan.” Williams might say that the irregularity of the markings and the general condition of the corpse indicate the blackened color is in fact damage incurred during the long voyage from Australia, which involved all the usual perils of the Age of Sail: storms, being becalmed in the heat of the equatorial regions, constant lurching of cargo, occasional flooding of the hold, quite a lot of rats, sailors drinking the alcoholic tincture in which some specimens were kept, etc. I recommend Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey-Maturin seagoing novels, often referred to as a combination of Jane Austen and Horatio Hornblower. All those events happened in the series. There was no actual European activity in Australia until the year Williams died, but work with me here.

Or Williams might, after dissecting the carcass, conclude that the bone structure is different enough from other species that the specimen doesn’t belong in genus Cygnus. It’s a non-white non-swan, so it doesn’t contradict the original WhiteSwan theory after all.

Again, my examples are far-fetched, but problems of interpreting experimental results abound, especially for cutting-edge theories. Did our expensive apparatus detect a superluminal neutrino or didn’t it? (And recall from an earlier post that the Eddington eclipse observations used “experimenter’s judgment” to reconcile three different measures of the deviation of starlight near the sun.)

The jargon is that “all observations are theory laden.“

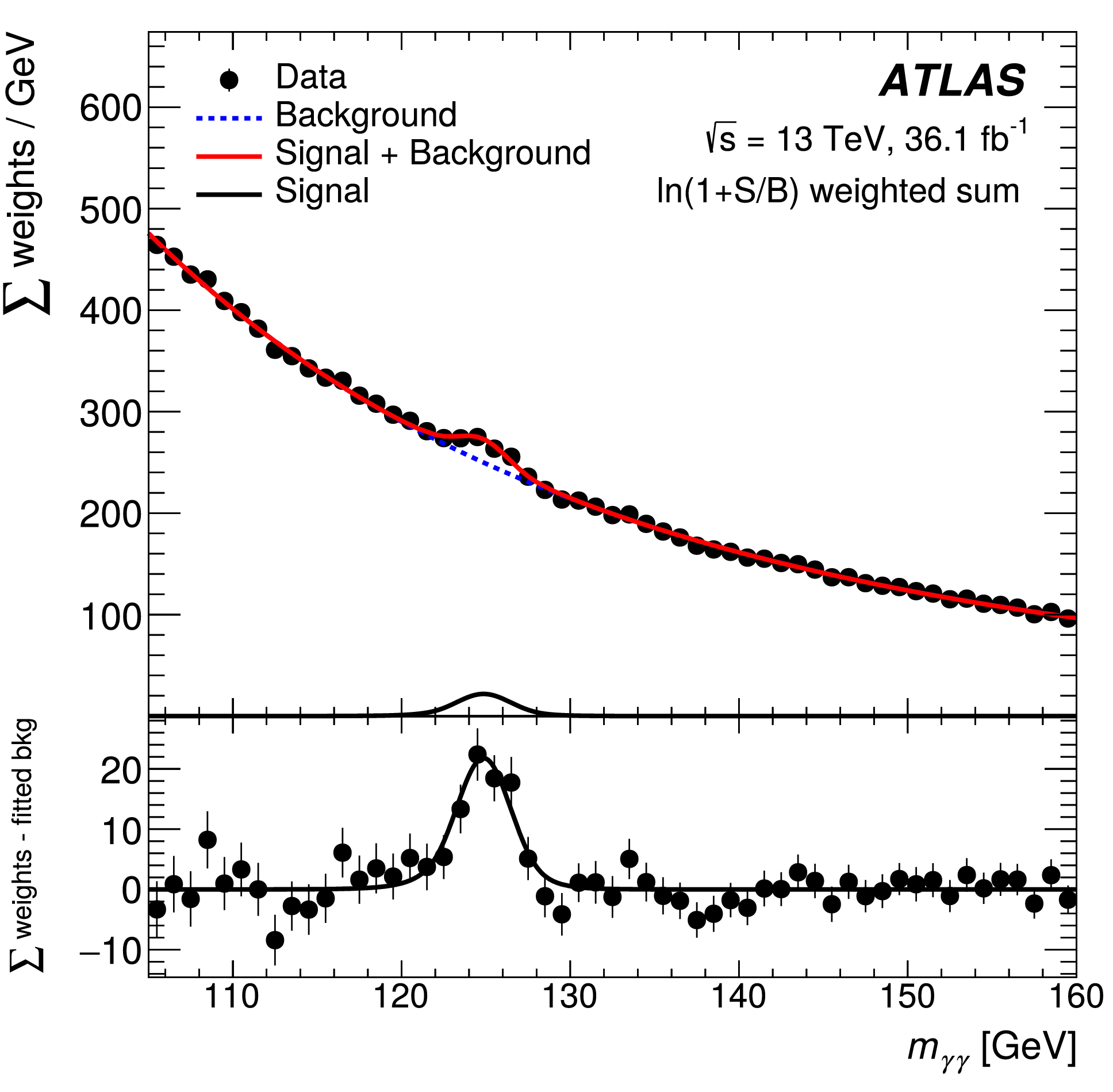

Note that the word “observation” is used both for real observations like Williams looking at a bone during dissection and a physicist at CERN looking at a graph representing a statistical analysis of gazillions of particle collider events. I personally think the word “observation” underplays the challenges of interpreting experimental results, but critical rationalists tend to be dismissive of experimenters anyway.

An 'observation' of the Higgs Boson. Click to enlarge in a new window.

An 'observation' of the Higgs Boson. Click to enlarge in a new window.

The irrational way to shift the discussion is for the community of people who care about the original theory (pro or con) to agree that enough people have failed to convincingly dispute the observation that the rest of us should just accept it and get on with our lives. That’s indeed what people do, and even Popper accepts that’s the best they can do.

𓅮𓅮𓅮

Because critical rationalism disallows an ad hoc amendment to a theory, Williams has to propose an amended theory that allows predictions of “novel facts” (Lakatos' term). Consider this amendment:

Claim AustraliaIsWeird:

- All swans outside Australia are white.

- Some swans in Australia aren’t white.

This might prompt a more concerted effort to look at Australian swans. But what’s the result?

- Maybe people find black swans. But we already knew they exist: Williams has the carcass of one.

- Maybe people don’t find black swans. Are they not looking hard enough? Was the swan Williams received the last black swan in Australia? (After all, there was a final passenger pigeon in North America and a final dodo in Mauritius.)

𓅮𓅮𓅮

The AustraliaIsWeird theory doesn’t seem very useful. It’s a “following the letter of the law rather than the spirit” sort of thing. A better revised theory would be:

Claim: HemispheresMatter:

- All swans in the Northern Hemisphere are white.

- All swans in the Southern Hemisphere are white, black, or some shade in between (combinations allowed).

At first sight, this doesn’t seem to add much. Nothing’s changed in the Northern Hemisphere, and we already knew there was a monochrome swan – it’s an exhibit in Williams' curiosity cabinet. But that’s a false impression because this is a toy example. Juxtapose it with real-world science:

-

The new swan theory is instructing naturalists to look elsewhere in the Southern Hemisphere than where (Williams assumes) they were looking: Australia. It’s not been unusual for theorists to tell experimenters to apply existing apparatus to a new “place” (a previously-ignored stretch of the electromagnetic spectrum, for example).

-

There’s no glory in finding a black swan any more, but a red swan… Naturalists will now be alerted to search for colored swans. That seems silly – it’s not like they wouldn’t have noticed a red swan before – but consider how particle physicists have spent the past century telling experimenters to build new accelerators to look for ever-more-exotic particles. They’re being told the equivalent of “learn to see a new color.”

Still, this is a bit boring, isn’t it? Suppose people search and no one finds a colored swan. Fine, we have more confidence that we can safely operate on the assumption that all swans are monochrome. Or instead suppose someone finds what will come to be called Dawn’s Turquoise Swan. Wow. Another non-white swan. Critical rationalists don’t favor the idea that a steady accumulation of small facts will add up to something important. I personally disagree.

Also, the theory gives no guidance for a more interesting question: why is there a difference in swan coloration between the two hemispheres? Suppose Williams ponders that, and jumps from it to another question: what else is different about the two hemispheres? Astronomy – Williams’s specialty – is sort of adjacent to meteorology, and that similarity reminds him that storms rotate clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and anti-clockwise in the Southern, due to something called the Coriolis force. Perhaps something about the Coriolis force affects the balance of humours in the body. And that could interact with magnetism: while the direction of the Coriolis “push” flips when you cross the equator, north stays north…

𓅮𓅮𓅮

In due time, Williams persuades an English correspondent to read his paper “On the relationship between Mr. Coriolis’s force and migration of bodily pigments” at The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge. In it, Williams lays out how the Coriolis force affects the humours, and how its direction (in relation to north) would produce a differential flow in those humours, and…

Such a paper could include multiple predictions:

- “Animals near the equator have more variation in hue because…”

- “The subtle shift in humours should also be detectable in the length of feather tubules, as length and color both rely on the balance of humours to…”

- “Consider raising an animal in a pen whose floor has a slight but constant slant. Because of the off-center gravitational force, the following should be observed upon autopsy….”

- “If a member of the Royal Society with a suitable estate were to raise generations of black Australian swans in England, he would notice a lightening of the feathers in descendants, akin to those trait changes achieved by successful dog and horse breeders, but without controlled mating.”

- “White sheep shipped to Australia will gradually darken (possibly patchily).”

This theory produces predictions that no one has made before, and there are more of them than in the earlier version of the theory. More about nature will be revealed by checking them. More is better.

𓅮𓅮𓅮

Big is also better, specifically: big surprises. Suppose you were asked two questions:

- “Did you hear that they found a black swan in Australia? So we’ve got black and white swans. What’s your guess for the odds of finding a colored swan somewhere in the world? You don’t have to give a number, just words like ‘high odds’ or ‘close to zero’ or whatever.”

- “Every sheep breed imported from the Continent to England (and not cross-bred with other breeds) stays the same color over the generations (black or white). What are the odds that a herd of white sheep shipped to Argentina will darken?”

You’d probably find the latter less likely.

Critical rationalists prefer their theories to make bold predictions, such as Einstein’s prediction that the sun’s gravity would bend starlight passing near it, or Edmund Halley’s prediction (using Newton’s theory of gravitation) that a comet he’d been observing would reappear in 72 years at such-and-such a precise time and position. (Halley died before the return of his comet. In an astounding coincidence, our very own Francis Williams was one of the observers who confirmed Halley’s prediction.

Williams was the first known Black “gentleman scientist” to (as was common among that sort) commission a portrait that alluded to his important observations, including Halley’s comet in the background.)

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

My interpretation of the critical rationalists' reasoning is that an unsurprising prediction isn’t much help in distinguishing between rival theories. It wouldn’t be hard to come up with multiple theories for why some swans are red, but finding another reason for the bending of light near the sun would be quite a challenge.

𓅮𓅮𓅮

What a prediction predicts might be observed, or it might not.

Popper calls a prediction that doesn’t pan out a falsification. Provided the observation is credible, preferably replicated, etc., it kills the theory. If you’re a proper (rational) scientist, you’ll want to quickly repair or replace it. To delay that process is irrational, although practicalities may require it for longer than one would like.

If a prediction is confirmed, Popper doesn’t attach much weight to that: “Oh look, another white swan.” Confirmation only allows (or encourages) people to keep doing what they were going to do anyway: check other predictions. As far as I can tell, Popper treats confirmations of bold predictions no differently than boring ones.

Lakatos has a different attitude. He calls a prediction that doesn’t pan out an anomaly. (Note the more tentative, less judgmental language.) To him, “theories grow in a sea of anomalies, and counterexamples are merrily ignored.“ For and Against Method, p. 99. To Lakatos, it’s rational to continue working on the theory and hope someone else explains the anomaly later – maybe decades later (as with the perihelion precession of Mercury, which took 56 years to get explained).

Like Popper, Lakatos doesn’t care much about lesser (or “timid”) predictions, but he thinks scientists are rational to be wowed by the bold ones. For example: For and Against Method, also p. 99. The following quote is on the same page.

For about a hundred hears after Newton had proposed this theory (the Principia was published in 1687) the French Academy offered an annual prize for whoever refuted the theory. About a dozen prizes were actually awarded, and then something happened.

The something was that Halley’s prediction – that his comet would reappear at certain place in the sky at a certain time – was confirmed.

After that, the French Academy did not put out any more prizes for the refutation of Newton’s theory.

Popper would have been displeased with the French Academy for giving up because of a confirmation (and likely with all the English scientists who had been ignoring the dozen refutations).

𓅮𓅮𓅮

So, some key points:

- Both of our critical rationalists agree scientists should eventually deal with anomalies, but they differ on the timing. Popper doesn’t allow many reasons for delaying, but Lakatos is happy with an indefinite delay.

- A new or revised theory should produce new predictions, ones not made before. Popper further requires that a new theory should also explain everything the old theory did. Lakatos is not bothered if some of the observations the old theory explains aren’t explained in the new. They can remain as anomalies for the new theory until someone gets around to them.

- Anomalies are more useful than confirmations because they drive further theoretical work. To Popper, confirmations might have some value by, for example, helping a theorist narrow down which theoretical claims a falsification implicates – but not much else. Lakatos thinks it’s a “metaphysical principle” (that is, one that’s not provable) that “highly falsifiable but well-corroborated theories are (in some sense) more likely to be true (or truth-like) than their low-risk counterparts.“ The quote isn’t Lakatos’s, but that of the author of The Encyclopedia of Philosophy article on Lakatos.