An occasional controversy in science is whether some theoretical “entity” is really real, or just a mathematical/modeling convenience. Ian Hacking has an interesting and eminently pragmatic answer that goes under the name “entity realism.” I believe him.

The positron (positively charged electron) was originally theorized by Paul Dirac as an implication of Dirac equation, “a unification of quantum mechanics, special relativity, and the then-new concept of electron spin.”

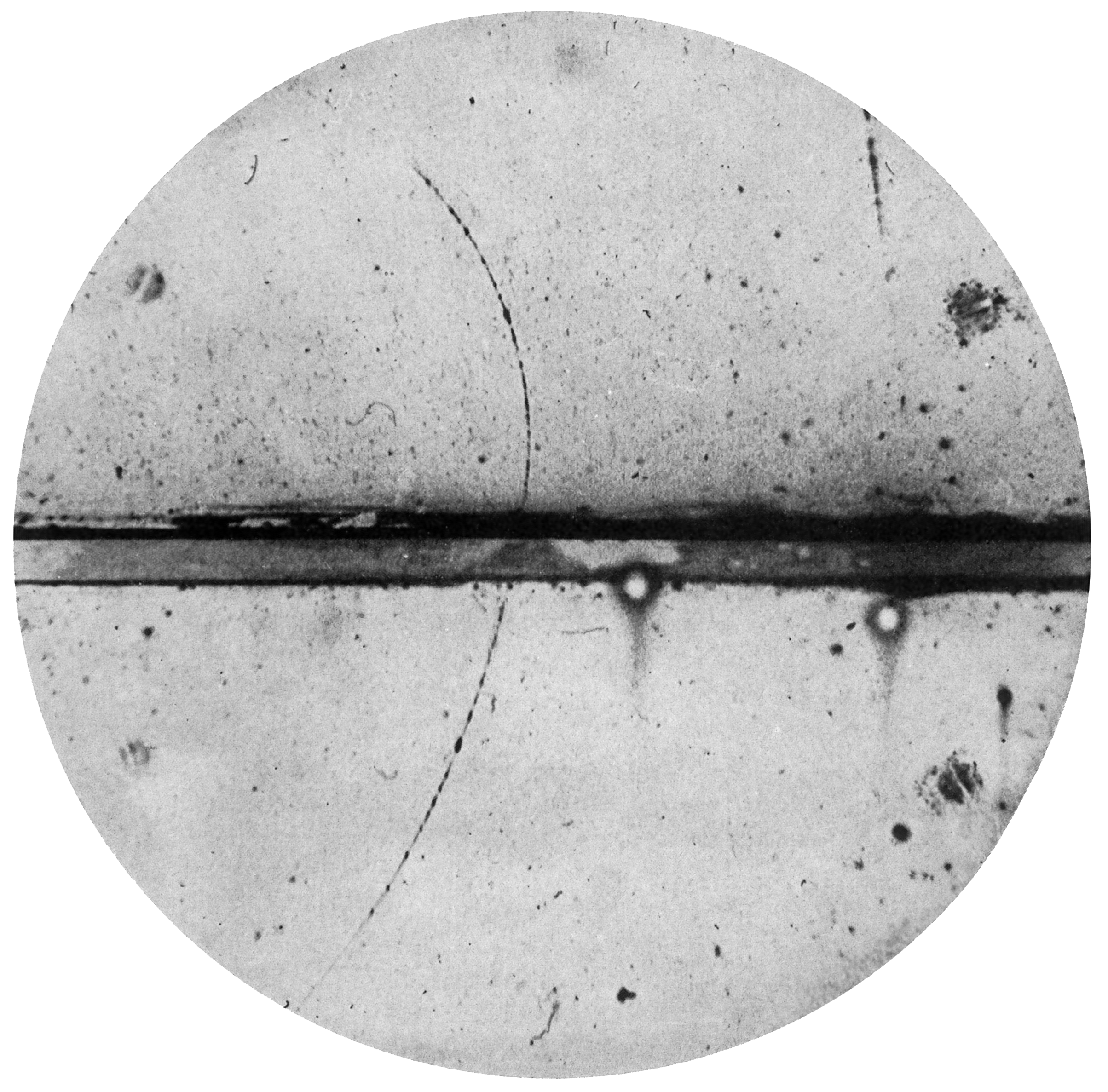

But was it a real thing, or just a side-effect of the math? Four years later, C. D. Anderson produced this picture: Anderson, Carl D. (1933). “The Positive Electron”. Physical Review 43 (6): 491–494. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRev.43.491. It is in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The little track in the image curves as sharply as an electron would, but in the opposite direction.

However, that’s not a picture of a positron. It’s a picture of a trail of droplets in supersaturated alcohol vapor. Yes, the trail is consistent with the idea of an electron-but-with-positive-charge, but that’s only indirect evidence that there is a thing that’s a positron. Maybe there’s a different explanation?

That seems weird to us, but only because everything we’ve ever read assumes the positron is a real thing. Early on, the subject was much more debatable and debated. Another example is perhaps more intuitive. In 1917, Einstein introduced the cosmological constant Λ in his theory of general relativity. That was to be consistent with the evidence that the universe is “flat” (neither expanding or contracting). Later, it got removed (or set to zero). That was consistent with the then-dominant theory that the universe’s expansion was slowing down. However, it now appears that the expansion of the universe is accelerating, so Λ is back, baby, with a positive value. Fine. But is Λ a thing? If so, what kind of thing?

Philosopher of science Ian Hacking was aware of the issue: when are we justified in saying a postulated entity is real? Another example: is light a particle or a wave? Or is that a meaningless question? In his Representing and Intervening (2012) he describes chatting with some experimenters who were searching for “free quarks” (possible entities with 1/3 the charge of an electron). Their plan was to use a small niobium ball, cooled to superconducting temperature and given an electric charge. (Because of superconductivity, the charge would never decrease.)

Because of the charge, the ball could be suspended in a magnetic field then moved around by varying the field. Hacking takes it from there:

The initial charge on the ball is gradually changed, and […] one determines whether the passage from negative to positive charge occurs at zero or at ±1/3e. If the latter, there must be one loose quark on the ball. […]

Now how does one alter the charge on the niobium ball? “Well, at that stage,” said my friend, “we spray it with positrons to increase the charge or with electrons to decrease the charge.” From that day forth, I’ve been a scientific realist. So far as I’m concerned, if you can spray them then they are real. (p. 23)

That last sentence is a catchphrase for entity realism, part of a partial shift of philosophy of science toward paying more attention to experiment (vs. theory). Things are treated as real if they provide experimenters with “manipulative success.”

The way I think of it is that the purpose of science is to be able to do more and more sophisticated experiments that build on earlier experiments and their results. That makes the connection between science and engineering tighter: engineers and experimenters are both using science to build things. Where they differ is in the purpose: one is in support of more experiments, and one is in support of… things like cars that need support in order to cross a river. They also differ in the amount of repetition. Experimenters trade practicalities the way engineers do, but there’s a lot more bridge-building than cyclotron-building work. For practicality-sharing, see Fujimura, Crafting Science, Pickering (ed.) Science as Practice and Culture (which contains a shorter version of Fujimura), and Galison Image and Logic.

This is essentially an application of William-James-style American Pragmatism. Something is true if it can be practically and usefully applied: “the ultimate test for us of what a truth means is the conduct it dictates or inspires.” Is the positron real? A thing? Yes, because you can use it in experiments that have nothing to do with positrons, that aren’t about positrons. Things become real when they become tools.