My next post is scheduled to be on Imre Lakatos’s “methodology of scientific research programmes.” I’m going to cast it as a failed attempt to make science rational that’s actually a good dissection of how scientists and people with a scientific temperament are persuaded (not-necessarily-rationally) to make big career bets.

But the question of why Lakatos was fixated on rationality makes for a good story. That’s this post.

Scientists have a right to feel smug.

Since the Scientific Revolution (~1543 - ~1687), science has progressed nicely. That is, scientists have figured out a way to spend extremely little time revisiting old controversies like phlogiston, spontaneous generation of animals, and the Ptolemaic universe. There are new controversies, to be sure, but rarely are they resurrected versions of older controversies. Moreover, the historical argumentation used in old controversies isn’t generally mined to get insight into today’s debates.

In contrast, philosophers (say) are always subject to getting sucked into more refined versions of skeptics' arguments from 2500 years ago. If you’re doing political philosophy, it’s still perfectly reasonable to refer to J.S. Mill’s On Liberty or Machiavelli’s Discourses on Livy. But college science courses don’t reach back to Newton’s Principia when teaching orbital mechanics or to Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species when teaching evolutionary biology.

Three methodologies

Naturally, when something works, people want to study how it works. What is it, exactly, that scientists are doing that accounts for the speed of their progress?

To oversimplify, this focus on method or methodology went through three overlapping phases:

-

Inductivism. The scientist worked by gathering observations and making generalizations from them. The generalizations were supposed to apply more broadly than the set of examples they came from. (Ideally, they would be universally true.)

Pretty much from the very beginning, people saw the problem with inductivism: if you see a bunch of white swans, and you induce that “all swans are right,” you’re going to get a nasty shock when someone presents you with a stuffed Australian black swan (Cygnus atratus). What was once universally true turns out to be true only of the swans of the northern hemisphere.

-

Waiting around for new examples and counterexamples is rather passive. It would be better to actively seek them out. The favored process became the hypothetico-deductive method. From observations (or wherever, really), you come up with a hypothesis. You should also come up with predictions of the form “I predict if someone sets up the following situation, they will observe thus and so.”

It’s called hypothetico-deductive because the predictions are supposed to flow from the hypothesis using only logical deduction, which is the only kind of logic that provides certainty. Induction over examples is still required, but at least part of the method provides certainty.

A classic example of the hypothetico-deductive method is Einstein’s theory of general relativity. Both his physics and Newton’s predicted a star’s light would bend as it passed near the sun, but a necessary consequence of Einstein’s theory would be bending twice that of Newton’s. So Einstein predicted that’s what one would see in a total solar eclipse. (It has to be total or the light of the sun would drown out the light of the star.) The experiment was tried, and Einstein’s amount of bending was observed. (Sort of.)

The hypothetico-deductive method proposed that a competition between hypotheses (like Newton’s and Einstein’s) should be decided by how well they were corroborated by predicted observations.

-

Falsificationism was due to Karl Popper, who wanted the scientific method to be still more stringent. He counseled that scientists should not consider a successful confirmation as giving more reason to believe in a hypothesis. Instead, what scientists should look for are falsified predictions: replicable counterexamples. (Popper was concerned with what he called the The Logic of Scientific Discovery, but there’s also a psychological angle: a person trying to falsify a hypothesis will probably come up with better experiments than someone merely trying to show the hypothesis works.)

If some random well-educated person talks about “the scientific method,” they’re most likely referring to Popper’s approach.

Motivations

Popper developed his approach in the early 20th century, which was a really weird half-century:

-

There was a pervasive sense of lost certainty. In mathematics, you had a crisis in foundations around the turn of the century. Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams was published in 1899, so Freudianism was really hitting its stride, causing some distress to people who’d fancied themselves working according to the dictates of reason, not some weird, alien “unconscious.” Psychology had forked off from philosophy in the late 1800’s (James' The Principles of Psychology was 1890), and it too cast doubt on the philosopher’s cherished rationality. The Great War (World War I) was a crazy slaughter, started for no sensible reason, and ground on well beyond the point of rationality or sanity. (The US Civil War was a precursor of the Great War’s industrial-scale slaughter, and it had effects on American intellectuals that presaged those of the Great War.)

In an entirely human reaction, people doubled down on the quest for certainty and embraced dogmatism more than ever. I take Popper to be playing in that arena. He had produced The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Yes, scientific conclusions could never be as certain as logical deduction like:

All men are mortal. Socrates is a man. Therefore, Socrates is mortal.But the scientific method could be made logical, certain (dogmatic), and rational. That fit the tenor of the times.

-

This was also an era where increasing bureaucracy, credentialism, and specialization had formalized the definitions of professions and shifted authority about a profession from its practitioners toward outsiders. Drawing boundaries was important. No longer could the “gentleman scientist” (like Darwin) be accepted through a process of impressing people already in the charmed circle: there are rules that any scientist worthy of the name must follow.

This was called the “demarcation problem": how do you distinguish between science and non-science (pseudoscience, metaphysics)? Popper particularly had it in for Freudianism and “scientific Marxism.” His scientific method ruled them out because none of their predictions could be falsified. Proponents always gave some reason why a particular contrary observation didn’t count.

Lakatos

Imre Lakatos (1922-1974) was of the generation after Popper. He was a junior colleague of Popper’s at the London School of Economics (which had a philosophy of science department). He later broke from Popper because their ideas were incompatible.

He shared Popper’s disdain for Marxism despite having been a fervent Stalinist in his youth. Important milestones in his journey away from communism were:

-

The Hungarian secret police arrested him in 1950 for “revisionism,” tortured him, and threw him into a forced labor camp that was modeled after the Soviet Gulag.

-

He was, outwardly at least, still a loyal Stalinist, and it seems to have been discovering Popper that caused his final break with communism. He publicly repudiated Stalinism in 1956.

This was three years after Stalin’s death and probably after Khrushchev’s February 1956 not-so-secret speech denouncing Stalin’s purges and his cult of personality. So perhaps not so brave as it seems, but someone with his background must have known that a tide that’s turned once can always turn back.

-

And, indeed, the Khrushchev Thaw that promised less repression and censorship across the Soviet Union did not prevent it from invading Hungary later in 1956. Lakatos – along with about 250,000 other Hungarians – fled the country.

Lakatos also shared Popper’s opinion of Freudianism.

Proofs and Refutations

Lakatos' work on the history (“logic”) of mathematics nicely sets the stage for his later work.

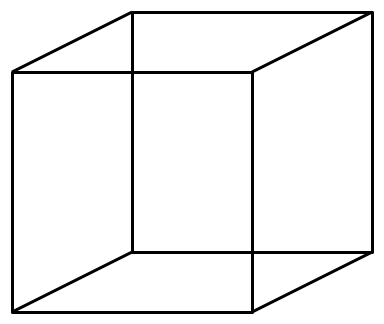

His posthumous Proofs and Refutations is derived from his PhD work. It largely deals with the Euler characteristic which (as originally formulated) claims the following is true for all polyhedra:

V means the number of vertices, E is the number of edges, and F is the number of faces.

2 = V - E + F

When Lakatos’s looked into the history of the Euler characteristic, he found that many people had proposed counterexamples. (“So what about this weird-ass three-dimensional structure? Do the vertices and edges and faces add up to two? They don’t, do they? Whatcha gonna do about that?)

Lakatos observed that mathematicians didn’t abandon the formula. Instead, they saved the formula using tactics Lakatos gave evocative names like “monster-barring” and “monster-adjustment.” That made them bad Popperians but, Lakatos observed, better mathematicians.

However Lakatos had, I think, a temperament that made him uncomfortable without rules. So things like “monster-barring” are, effectively, a list of rules about when it’s rational to break what you might call “first-level rules.”

The odd couple

Weirdly, Lakatos became great friends with Paul Feyerabend, who had quite the opposite temperament. That almost led to a great cooperative venture. Here’s the beginning of Feyerabend’s preface to his most famous book, Against Method:

In 1970 Imre Lakatos, one of the best friends I ever had, cornered me at a party. ‘Paul,’ he said, ‘You have such strange ideas. Why don’t you write them down? I shall write a reply, we publish the whole thing and I promise you – we shall have a lot of fun.’

Unfortunately, Lakatos died just before Feyerabend was to send him his draft, so only the Feyerabend part was ever published. Using examples, Feyerabend argued that Lakatos’s dream of rational rules and meta-rules would never work. Whatever rules you try to impose, great scientists will “cheat.” Moreover, they could not have achieved their greatness without breaking the rules.

Feyerabend was very much an “the end justifies the means” guy. Lakatos – perhaps because he was very much that kind of person in his Stalinist days “[The young] Lakatos decided that there was a risk that [a new member of his Marxist group] would be captured and forced to betray them, hence her duty, both to the group and to the cause, was to commit suicide. A member of the group took her across country to Debrecen and gave her cyanide.” source – seemed unwilling to go that far. There had to be good means that would, rationally, lead to good ends.

Postscript

Perhaps incorrectly and definitely simplistically, I think of Lakatos as being at the tail end of prescriptive philosophy of science: the quest for a way to do science that could be justified rationally from first principles. What came to be called “science studies” was more heavily influenced by sociology and anthropology than philosophy. It’s characterized by:

- Less of a focus on Great Men (Galileo, Newton, etc.) and more on run-of-the-mill scientists.

- Realizing that perhaps physics isn’t the model for all sciences. Maybe biologists weren’t just wanna-be physicists and had their own way of doing things that worked fine for them.

- A greater focus on experimenters, whom pretty much everyone – Kuhn, Popper, Lakatos, Feyerabend – had brushed aside as mere mechanics.

All of this got caught up in the “science wars,” which were a silly offshoot of the silly culture wars that started in the 1980’s I documented some of the culture wars in a series on “political correctness.” 1984, 1987, 1990, 1991. Ironically, back then it was the culturally right that cast themselves as defenders of science and objective reality and the culturally left that were anti-science relativists. Though, as I say, the whole thing was silly. See Hacking’s The Social Construction of What? for a dissection of the science wars. Did the Science Wars Take Place? is an interesting (though more opinionated and intemperate than I’m comfortable with) take from an “a plague on both your houses!” anarchist. (Since the author doesn’t approve of the concept of intellectual property, there are ungated PDFs and ePubs at the site, in addition to the option to buy a hardcopy.) and seem unkillable.

I haven’t kept up with the field this century, but I found Godfrey-Smith’s Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science a good read.