Although “political correctness” (in its modern meaning) was occasionally used prior to 1990, that was the year it went mainstream. On campuses, the name apparently took hold strongly and swiftly at the beginning of the 1990-1991 academic year (starting in the fall). Word spread in the media, probably most influentially with an October 1990 New York Times article by Richard Bernstein. It got a big boost when then-President George H.W. Bush said, in a commencement speech at the end of that academic year (May 1991):

“The notion of political correctness has ignited controversy across the land. And although the movement arises from the laudable desire to sweep away the debris of racism and sexism and hatred, it replaces old prejudice with new ones. It declares certain topics off-limits, certain expression off-limits, even certain gestures off-limits.”

The Wikipedia article on political correctness says:

“[I]t was Dinesh D’Souza’s Illiberal Education: The Politics of Race and Sex on Campus (1991) which ‘captured the press’s imagination’.” For the quote, they cite Whitney, D. Charles & Wartella, Ellen (1992). “Media Coverage of the ‘Political Correctness’ Debate.” Journal of Communication. 42 (2): 83, which I have not read (paywalled).

So that was an obvious next book to read. Throughout this post, all page numbers are from a scanned version of the book at archive.org.But when I did, I found myself with a problem. This series started with Bennett complaining about current trends in the humanities. The right ideas weren’t being taught. Then, in the second installment, I covered Bloom complaining about the same thing. He also introduced what I thought of as now-typical anti-PC rhetoric or argumentation, things like:

- An expanded list of gripes (it’s not just what’s being taught; it’s rock music and German philosophers and a bunch of other things).

- A tendency toward catastrophism.

- The sense that there’s a right word and a wrong word for any subject X and that using the wrong word has consequences. (“Words have power.")

- The Gish gallop as a way of wearing down the potentially-skeptical reader.

With the third installment, I noted a shift away from ideas to characterizing the world as a place of named groups (especially feminists) contending for power. I continued to note rhetorical techniques, like nutpicking, the “argument from incredulity,” and what I’ve come to think of as the “Kimball quote.“ It’s a particular way of summarizing a longer passage of text by embedding quotes of “individual” words or short phrases in context-setting text such that “every quoted word” appears in “the original,” but the message is “distorted.”

I also noticed that dishonesty was creeping in, in an “all’s fair in love and war” sort of way.

D’Souza is in this lineage, and makes gestures toward the arguments and concerns of his predecessors, but it doesn’t seem to me his heart is in it. For example, Bloom especially but also Kimball are obsessed with moral relativism as what the humanities are teaching, with nihilism as the end result. Avoiding that is why the humanities need to be restored: relativism and nihilism are incompatible with human flourishing. D’Souza rarely mentions the topics. When he does, he characteristically links them to power: “In other words, Fish seemed to recognize, relativism paves the way for a toppling of the old rules, and the establishment of new ones based on political strength.” (p. 175) Bloom and the others are more concerned that relativism and nihilism are incompatible with human flourishing What he cares about is exposing (or inventing) evidence that bad professors (not just in the humanities) have allied with unqualified Black students and radical feminist students to seize effective power from feckless and cowardly administrators. And they use that power to, yes, teach students wrong thought, but more urgently to intimidate or destroy both students and professors who fail to submit (by speaking truths that should not be spoken). That (by 1991) had led to an increase in racial conflict as primarily White students act out their justified resentment. Unless something is done, this conflict would spill out into society at large:

“It is clear that the heavily publicized racial confrontations on campus are mere symptoms of much deeper changes that are rapidly under way, with far-reaching consequences for American society.” (p. 2)

“[M]ost minority graduates will admit, when pressed, that if their experience in college is any indication, the prospects for race relations in the country at large are gloomy. If the university model is replicated in society at large, far from bringing ethnic harmony, it will reproduce and magnify the lurid bigotry, intolerance, and balkanization of campus life in the broader culture.” (p. 230)

I think his prediction fell pretty dramatically short, but that’s not important for this post.

The problem

In 1991, Dinesh D’Souza might have been given the benefit of the doubt. His career since then has made it clear he fits Harry Frankfurter’s definition of a bullshitter:

“[B]ullshit is speech intended to persuade without regard for truth. The liar cares about the truth and attempts to hide it; the bullshitter doesn’t care whether what they say is true or false.“ Frankfurt’s description of the liar caring about the truth never really rang true for me, but that’s of no matter here.

D’Souza’s 2022 movie and book 2000 Mules demonstrates that well. When your distributor disavows the film and the book, pulls them from distribution, and apologizes, that’s generally a bad sign.

I read Illiberal Education knowing D’Souza’s reputation. Two things struck me:

- A lot of this is (with the benefit of hindsight) obviously bogus.

- Reviewers of the time didn’t notice that.

So I became interested – maybe slightly obsessed – by D’Souza’s mechanism. He’s not credible. But people treat him as if he were. What tricks does he use? How could reviewers have seen through the trickery?

So I’ll finish this series with some comments on his ordinary contributions to the anti-PC discourse and then start another series on the topic of “How could reviewers of the time – or you today – spot D’Souza’s type of bullshit without doing a lot of work?”

Hey, a guy’s gotta have a hobby.

The non-lying kind of rhetoric

In some ways, D’Souza’s structure mimics Kimball’s: it’s an anthropological travelogue. The author visits strange tribes and returns to tell us of their strange customs. (Kimball visited mostly academic conferences; D’Souza focuses on particular campuses, each one serving as an example of a theme.)

D’Souza’s innovation was to take on the aspect of the journalist. I envision Kimball in the back row of a lecture hall, with a recorder and note pad, not talking to people. D’Souza interviews people and summarizes those interviews in his book.

He also purports to read books and summarize them. Sections of D’Souza’s book mimic the work product of op-ed pundits like David Brooks or George Will, people who read a book and write a column telling us how it confirms what they already thought. He also brings to bear two other staples of the op-ed page or the longer quasi-opinion journalism you’ll find in the New Yorker, Atlantic Monthly, or New York Review of Books:

- use of newspaper articles or op-ed pieces as cited sources.

- lots of numbers; use of statistics

I suspect Illiberal Education “captured the press’s imagination” because it’s written in the form they’re used to. It’s a work product that looks like their own. A cynic might think part of Illiberal’s appeal is that it’s easier to convert D’Souza’s text into an op-ed. It provides the needed elements: statistics to cite, telling quotes, and such.

Issues defined by people; people defined by issues

Suppose there’s an issue, such as the purpose of the humanities. There will naturally be a range of opinions about it. Even though it’s almost always an oversimplification, people tend to think of those opinions as being roughly along a linear spectrum.

Because people like D’Souza tend toward ingroup/outgroup or “us vs. them” thinking, there’s a need to have two distinguishable sets of opinions, with one group associated with “us” and the other with “them.”

Given that the point of discussing an issue is to rally the troops, having nuances be visible is counterproductive. So “their” opinions will be collapsed down into one. Although treated as representative, the chosen one will typically be extreme. So people like Bloom and Kimball describe their opponents in the humanities as huge proponents of nihilism.

The same process could take place with a different issue. For example, to what extent should the government intervene in the economy? Some people favor doctrinaire Marxism, others a Scandinavian-style social welfare state, others something akin to Christian Democrats in Europe or Democrats in the US. Opponents of all of those will lump them together under “socialism” or “Marxism.”

Except that the enemy isn’t so much ideas as the people having the ideas. (Power, remember?) So it’s cognitively efficient to go from “person A is a radical feminist” to “person A is a Marxist” without having to actually check. It’s true that those opinions are likely somewhat correlated. Richard Rorty believed his politics should be organized around minimizing the cruelty people do to others. That given, it wouldn’t be surprising to find he’s some sort of a feminist and a supporter of social democracy. But I don’t think an actual correlation is necessary. For example, those of Kimball’s “tenured radicals” who were Marxist men in the sixties were quite notoriously not feminists. “Women who favoured radical feminism collectively spoke of being forced to remain silent and obedient to male leaders in New Left organizations. They spoke out about how they were not only told to do clerical work such as stuffing envelopes and typing speeches, but there was also an expectation for them to sleep with the male activists that they worked with.” These sorts of facts are ignored because it complicates the message. And, in the lineage of books I’ve been discussing, a radical feminist must also have a predictable – and extreme – position on the humanities in higher education. The need is for simple answers and clear boundaries.

The drive for clarity also eliminates nuance from the “us” side. The range of valid opinions shrinks, often concentrating at an extreme.

In the end, the issues become little more than a way to identify who’s on which of two sides. The point of an opponent’s opinion is to identify her as an opponent. And if an opponent has a silly idea on one issue, she necessary has a silly idea on all issues, and so does everyone else who can be identified as being in the same out-group.

This focus on “their” silly ideas and arguments tends to make “our” arguments silly too, because the point is no longer refutation of an idea but to remind our side of the perfidy of our enemies. Silly, “gotcha”-style ideas work best for that.

“To be sure” and the mushy middle

To me, Kimball’s book – ostensibly about the state of the humanities – comes across as weirdly, even creepily, obsessive about the tangential topic of feminism. But Kimball I think was writing for those already mostly convinced: the cluster of people on his side. (The second picture above, also shown to the right.) They already have negative feelings toward feminism, so they won’t mind him railing against it. It serves his goal of presenting the Other as wrong and extreme about everything as well as anything else would. Because, remember, all issues are connected.

D’Souza has taken on a different goal. The people in the middle are his primary audience. He wants to pull them to his side. To do that, he has to appeal to those people’s conception of themselves as being fair, judicious, and objective – by presenting that appearance himself.

In his New Yorker review of Illiberal, Louis Menand puts it well: Louis Menand, “Illiberalisms,” The New Yorker, 20 May 1989, pp. 101-107. Archive version; subscription required.

“The tone throughout ‘Illiberal Education’ is that of a man who is curious about the reports he has been hearing of campus strife over issues involving race and sex, and who, as a friend to liberal learning, is sympathetic to all the parties involved (or nearly all, for he cannot find a good word to say about homosexuality). D’Souza was born and raised in India and came to the United States as an exchange student in 1978, when he was seventeen, and in his opening chapter he says that he feels ‘a special kinship’ with minority students, and believes that the university is ‘the right location for them to undertake their project of self-discovery.’ " (Menand, p. 101) D’Souza’s career demonstrates this was an act. As Menand notes, D’Souza’s previous claim to fame was as editor-in-chief of The Dartmouth Review, an off-campus newspaper famous for such stunts as “an interview with a former leader of the Ku Klux Klan, illustrating it with a staged photograph of a black man hanging from a tree on campus” (Menand, p. 101) and then as editor of Prospect, an alumni magazine broadly opposed to women at Princeton, where among his accomplishments he wrote an article “in which the sex life of a female undergraduate, who had declined to be interviewed by the magazine, was described without her consent” (p. 102). Nice guy. As Menand notes, “Apart from brief references to his association with The Dartmouth Review and to an ‘alumni magazine’ that he edited at Princeton, D’Souza makes no mention of his own contributions to the campus tensions he now writes about with such concern” (Menand, p. 102). Later books, like The Enemy At Home: The Cultural Left and Its Responsibility for 9/11 and The Roots of Obama’s Rage show him reverting to form. So it’s fair to believe his persona in Illiberal Education was just a façade.

Because of his audience, D’Souza has to tread somewhat carefully, frequently using what I’ve come to think of as a “to be sure” insertion, which most often has this structure:

- Axioms (often more alluded to than spelled out) and evidence supporting his conclusion.

- Preliminary statement of the conclusion.

- The former two may come across as harsh, so: some seemingly softening statement agreeing with what his mushy-middle reader might be thinking.

- Restatement and elaboration of the conclusion, which is – importantly – unaffected by the softening statement.

So one chapter discusses replacing some of the “Western canon” of “the best which has been thought and said” (Matthew Arnold) with works by women and ethnic minorities. He’s against it because women’s and (most) minority writing just isn’t up to snuff. But then he softens the claim by acknowledging women have had it tough:

“The risk of attempting curricular accommodation based on race and gender is that it can result in lesser works being taught simply because of the skin color or gender of their authors. In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf poses a difficult and important question: why has there never been a female Shakespeare? Woolf speculates that if Shakespeare had had an equally gifted sister, she could never have made it onto the London stage, and probably would have died anonymously. ‘A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction,’ Woolf argues. Woolf’s brilliant analysis is justly celebrated by feminists, but it leaves many of them deeply uncomfortable, and it is not hard to see why. In debating why there is no female Shakespeare, Woolf concedes that there is no female Shakespeare.” (p. 82)

D’Souza has headed off a possible suspicion that he thinks women are inherently inferior writers. He would probably concede that – now that women do have rooms of their own – we might eventually get a female Shakespeare. We shall await her with anticipation. In the meantime, his conclusion remains: the canon should not be tampered with. One might think that a slave’s memoir might be better at teaching what servitude does to the soul than, say, Shakespeare’s The Tempest (with the two slaves Ariel and Caliban). But there’s something of a Catch-22. The topics the canon addresses well are the topics worth addressing. So we can say that Virginia Woolf is better at teaching what it means to be a woman entering a man’s world than Shakespeare would be, but no one in the canon addresses that topic, so it oughtn’t be discussed. May I offer Othello instead? Close enough?

D’Souza’s opening argument about affirmative action (particularly at Berkeley) is that Blacks are taking university slots away from better-qualified Asians and Whites. His audience in 1991 was likely to be White university graduates who expected to send their children to college. So D’Souza’s stoking a fear: will my child’s spot at Berkeley go to someone else?

But there’s also likely to be a countervailing emotion: a sense of guilt or regret over that whole slavery thing, and Jim Crow, and redlining, and all that. His audience might believe or hope racism is over, but still also think 400 years of it might have left some residual or systemic effects that aren’t just going away by themselves. D’Souza needs to suppress that reaction.

One way is to focus on Asian students, especially the children of immigrants, as victims of affirmative action. Whites can feel upset on their behalf, and skate past questioning their own interests.

Another is to refer to “blacks, Hispanics, and American Indians” overwhelmingly often, so that D’Souza comes across as talking about a system (affirmative action) rather than a group (Blacks). I don’t think he succeeds particularly well (as I’ll discuss in a later post), but he makes the effort.

Most effectively, to my mind, he goes to some pains to claim that affirmative action is bad for Blacks too.

- Colleges do a lousy job of offering post-admission help, so Black drop-out rates are high.

- They end up taking easy majors at Berkeley instead of the better majors they could have managed at lesser schools like Davis or Irvine.

- Because Blacks know the White and Asian students around them think they’re inferior, they huddle together at de-facto Blacks-only cafeteria tables, Black fraternities, Afro-American Studies departments, and so on. That doesn’t protect them from developing a certain amount of self-hatred and shame, though.

- The resentment felt by more-qualified students leads to increased racial tension on campus, plus racist incidents, which is not good for Blacks.

- After college, employers will doubt their qualifications.

So, to be sure, we all want to help the Blacks overcome the legacy of those 400 years, but affirmative action isn’t the way.

The rhetoric of reaction

In his The Rhetoric of Reaction: Perversity, Futility, Jeopardy, Albert O. Hirschman calls the “perversity thesis” one of the key narratives of conservatism:

“[A]ny purposive action to improve some feature of the political, social, or economic order only serves to exacerbate the condition one wishes to remedy.”

D’Souza embraces the perversity thesis by claiming attempts at “diversity” intended to sooth racial tensions have in fact exacerbated them.

Next, we have the “jeopardy thesis”:

“[It] argues that the cost of the proposed change or reform is too high as it endangers some previous, precious accomplishment.”

That’s an important complement to the “to be sure” tactic. To be sure, there are some lessons – what it’s like to be a slave, or a woman – that the canon doesn’t address. But there’s only so much room in a curriculum. If we taught testimonies of the recently oppressed, we’d lose the best which has been thought and said. All of it: in typical catastrophist fashion, D’Souza vastly exaggerates the tradeoff. If we “expand the canon,” we’ll lose Western civilization’s technology for creating noble souls; society will become a blind struggle between self-identified victims and their supposed oppressors, which is just what they intend!

Hirschman’s third rhetorical technique is the “futility thesis”:

“[It] holds that attempts at social transformation will be unavailing, that they will simply fail to ‘make a dent.’

As a catastrophist, D’Souza can’t use this one. His goal is to alarm and enlist the mushy middle. He can’t do that by saying the politically correct won’t make a dent; he has to say they’ll destroy the whole car.

There are no hard decisions

Humans (and other primates) have a strong sense of fairness. If you can persuade people something is unfair, they’ll be against it. D’Souza’s chosen task is to persuade the reader that race-sensitive college admissions are unfair. Hence the following:

“In 1988, for example, the average white freshman at the university [of Virginia] scored 240 points higher on the SAT than the average black freshman.” (p. 3) The SAT (Scholastic Aptitude Test} is a one-sitting summary test of performance in two categories, “Reading and Writing” and “Math.” Both are measured on an 800 point scale. Because two numbers are hard to keep in your head, I guess, people usually report the sum of the numbers.

He is using a (mostly implicit) model of university admissions, one with these characteristics:

- The purpose of a university is to put the maximum amount of education into each student’s head.

- Some students have more room in their heads for education. We call this their “academic aptitude.”

- Academic aptitude is an ordinal, or linear, variable. You can line up all the candidates for the freshman class in order of aptitude. If you have 100 available places, you should take the first 100.

- The value of the aptitude variable is knowable. It can’t be directly measured, but it can be inferred from measurable quantities like the SAT score and grade point average. In secondary (pre-college) education, a US student will take some tens of classes over a period of four years. Each provides a final numerical summary of the student’s performance. The average of all the scores is the grade point average (GPA). It will lie between one and five.

- The inference procedure can be objective, meaning that any two people would produce the same ranking.

The replacement he proposes for race-based preferences uses the same rigid and simplistic model:

“This means that, in admissions decisions, universities would take into account such factors as the applicant’s family background, financial condition, and primary and secondary school environment, giving preference to disadvantaged students as long as it is clear that these students can be reasonably expected to meet the academic challenges of the selective college. […] Universities seem entirely justified in giving a break to students who may not have registered the highest scores, but whose record suggests that this failure is not due to lack of ability or application but rather to demonstrated disadvantage.” (p. 251)

He claims that would be easy:

“Ordinarily it might seem an extraordinarily complex calculus to weigh such factors as family background, income, and school atmosphere. Fortunately, colleges already have access to, and in many cases use, this data. The application forms give applicants ample opportunity to register this information, and the financial aid office assiduously tabulates family assets and income. By integrating admissions and financial aid information, universities are in a good position to make intelligent determinations about socioeconomic factors that advanced, or impeded, a student’s opportunities.” (p. 252)

Would it really? Financial aid offices use their data to estimate ability to afford college. He’s saying it would be straightforward to use the same objective data to adjust GPA and SAT estimates of academic potential. Instead of:

academic_potential = f(SAT, GPA)

… we’ll use:

academic_potential = f(SAT, GPA, ability_to_afford_college)

… and take the 100 students who score the highest.

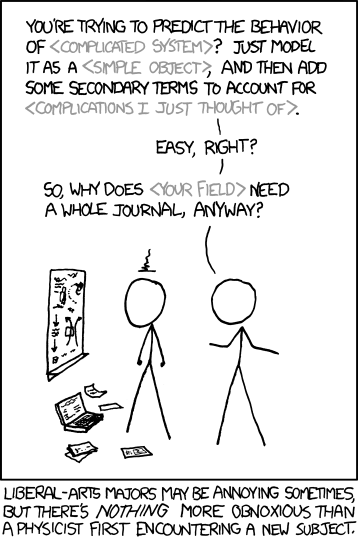

Dinesh D’Souza, Bachelor of Arts in English, Dartmouth, 1983, is at heart a stereotypical STEM bro:

Click for XKCD Explained

Life’s not that simple, my dude.