This is third in a series examining the evolving rhetoric used by those who believe “political correctness” is a threat to Western, especially American, civilization. (I’ll call that “anti-PC rhetoric” for short.) We’re now up to 1990 with Roger Kimball’s Tenured Radicals: How Politics Has Corrupted Higher Education. I’m working from a scan of the 1991 paperback edition. I believe it’s the same as the 1990 hardcover, except for the addition of an epilogue. There were two later editions, in 1998 and 2008, but I mention only the 1998 edition, and only briefly.

I previously covered a committee report by William Bennett and a book by Allan Bloom. Those presented something of an insider’s view: academics in the humanities alarmed about the humanities. Kimball represents a shift to something of an outsider’s or populist perspective, as Kimball was not an academic, but rather worked for The New Criterion, a journal in the venerable tradition of the independent or “little” magazine of literature and culture. (He is currently editor and publisher.) The emotion intended to be provoked has shifted, I think, from anger or alarm to disgust, which necessarily led to changes in rhetorical technique – ones that have persisted, and even dominated, to this day.

The message

Although this post is mainly about how the text works (achieves its effects), I should have a bit about its message, for context. The message has not changed too much from Bloom.

The “tenured radicals” of the title have, as a goal, “nothing less than the destruction of the values, methods, and goals of traditional humanistic study” (p. xi). They have a “blueprint for a radical social transformation that would revolutionize every aspect of social and political life, from the independent place we grant high culture within society to the way we relate to one another as men and women” (p. xviii).

“The truth is that when the children of the sixties received their professorships and deanships they did not abandon the dream of radical cultural transformation; they set out to implement it. Now, instead of disrupting classes, they are teaching them; instead of attempting to destroy our educational institutions physically, they are subverting them from within. Thus it is that what were once the political and educational ambitions of academic renegades appear as ideals on the agenda of the powers that be. Efforts to dismantle the traditional curriculum and institutionalize radical feminism, to ban politically unacceptable speech and propagate the tenets of deconstruction and similar exercises in cynical obscurantism: Directives encouraging these and other radical developments now typically issue from the dean’s office or Faculty Senate, not from students marching in the streets.” (pp. 166-167)

The mechanism by which radical cultural transformation will be achieved is by teaching students the wrong things and by writing scholarly works containing the wrong messages. For example:

“At many colleges and universities, students are now treated to courses in which the products of popular culture – Hollywood movies, rock and roll, comic strips, and the like – are granted parity with (or even precedence over) the most important cultural achievements of our civilization.” (pp. xii-xiii)

Even when it comes to less frivolous cultural artifacts, the things being studied have changed. “[P]erhaps the most notorious case of canon “[The canon is] the embodiment of high-culture literature, music, philosophy, and works of art that are highly cherished across the Western hemisphere, such works having achieved the status of classics.” – Wikipedia revision [was] the dropping of the Western culture requirement at Stanford University in the spring of 1988” (p. 27) in favor of one that “must include ‘works by women, minorities and persons of color,’ and that at least one work each quarter must address issues of race, sex, or class” (pp. 2-3). A snarky reviewer noted that Stanford’s requirement dated back only eight years, to 1980, making it not exactly a huge abandonment of traditional support for Western culture.

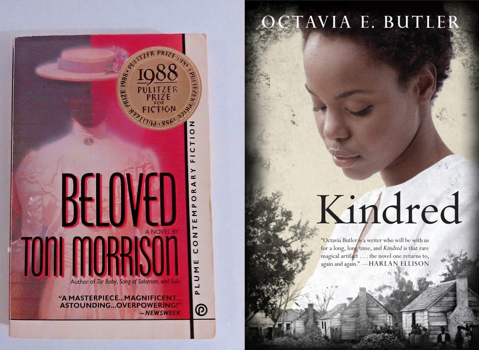

What I suppose this means is that US students grappling with the legacy of slavery – something every educated citizen should do – might do it by reading and discussing books by contemporary Black women – Beloved or Kindred, say – rather than Aristotle or the Bible. To a canon-ist, this is incorrect. While the contemporary books might have merit, the older writings are more correct (having stood the test of time) and more central to Western and American culture.

Having graduated without a solid grounding in the dominant culture, students will not be able to (nor be inclined to) perpetuate it.

Moreover, humanities professors believe that their writings will, in themselves, affect the broader society:

“And – as anyone with even a passing acquaintance with the products of the new academic scholarship knows – writing no longer means attempting to express oneself as clearly and precisely as possible, but is rather a deliberately ‘subversive’ activity meant to challenge the ‘bourgeois’ and ‘logocentric’ faith in clarity, intelligibility, and communication." (p. xv)

Having brushed up against some of the authors Kimball attacks (Stanley Fish and Barbara Herrnstein Smith) as well as others of their ilk, I think Kimball is right: many did (or do) think that writing fairly opaque works to be read by their fellow academics is a radical, even political, act. Except for the deconstructionists. At the time Kimball was writing, Marxists like Terry Eagleton loathed deconstructionists precisely because they were so apolitical they were, in effect, another face of “bourgeois liberalism.” That’s a hobbyhorse (of mine) for another day, though. Some probably did believe they were continuing their youthful “dream of radical cultural transformation.”

Where I differ from Kimball is that seems to me kind of… pathetic. Stanley Fish going on about “the authority of interpretive communities” in a book read only by humanities professors, graduate students, and a few weirdos like me is not exactly manning the barricades. Fish later became a “public intellectual” – he had an occasional column in The New York Times from 1995 to 2013. I don’t think he was very publicly known at the time Kimball wrote. Lenin and Trotsky and even Stalin felt compelled to write abstruse theoretical tracts, but Trotsky’s founding and leadership of the USSR’s Red Army (for example) was a lot more consequential.

Given the ineffectuality of academic writing, it’s odd that so much of Kimball’s text is not about how the youth are being corrupted, but about what professors say and write to each other. He’s supposed to be warning the reader of what tenured radicals are doing to society, but the vast majority of his words are about what they’re doing with each other in the privacy of their seminar rooms. I’m not the only person to notice that. One reviewer wrote, “The book often strays too far from its main thesis, giving the impression that the thesis itself was an afterthought.”

The rhetoric

Kimball uses nutpicking and “the argument from incredulity,” two techniques that fit together nicely. So, to start, what are they?

Per RationalWiki.org, nutpicking is…

“the fallacious tactic of picking out and showcasing the nuttiest member(s) of a group as the best representative(s) of that group — hence, ‘picking the nut.’

“This fallacy is committed when an arguer cherry picks a poor representative of a group to use as an ad hominem against them. For example, anti-feminists frequently paint people who support feminism as ‘feminazis’ by highlighting examples of ridiculous or cringeworthy behavior from select individuals, rather than critiquing points addressed in mainline feminist writings.”

Per Wikipedia, the argument from incredulity is…

“a fallacy in informal logic. It asserts that a proposition must be false because it contradicts one’s personal expectations or beliefs, or is difficult to imagine.”

“Arguments from incredulity can sometimes arise from inappropriate emotional involvement, the conflation of fantasy and reality, a lack of understanding, or an instinctive ‘gut’ reaction, especially where time is scarce.“ My emphasis. As I noted in the “Gish Gallop” section of the Bloom post, the reading experience often doesn’t encourage the reader to stop and think, but rather to move on to the next paragraph. Also, a “gut reaction” can be manufactured – or “primed” – with appropriate rhetoric.

Nutpicking and the argument from incredulity are closely related. Nutpicking focuses on particular people, but they’re nuts because their ideas are ridiculous. And, typically, one of the reasons for being incredulous about an idea is because of the specific person or type of person who believes it.

Kimball’s book is structured as a series of anecdotes, really. Like many traditionalist humanities people who scorn the social sciences, Kimball doesn’t count things or take surveys. He’d much rather present another anecdote than crunch numbers to present, say, averages. It’s the sheer number of anecdotes that is meant to compel agreement. We are supposed to assume they’re representative or typical. In a way, it’s an episodic, fairly unstructured travelogue. So he might visit a conference or symposium, record the speakers and the audience, and extract anecdotes from the recordings. Other times, he will “visit” a book, various issues of a journal, or writings by (or about) a particular author, and return with pictures of the outrageous things he found.

I think it’s important that, unlike Bloom and Bennett, Kimball provides numerous short quotes from various named academics. It’s easier to despise or resent a person than an idea. And quotations provide verisimilitude: it’s not Kimball attributing nutty ideas to these people. You can read their very words! But, as you’ll see, the quotations are short, so the reader lacks needed context. Kimball supplies that in a way that biases the reader toward his (Kimball’s) preferred and invariably simplistic interpretation.

In what follows, I’ll pick apart his anecdotes to see how their rhetoric works. I’m aware that I’m making anecdotes out of his anecdotes and so forcing you to trust that I’m quoting fairly and supplying needed context. Fortunately for you, Kimball’s entire book is available online for free, For now. I thought the Internet Archive had lost in court the ability to lend scanned books, even for short periods. Don’t tell anyone, but it still works as of October 1, 2024. so it’s not hard for you to click through, go to a page, and see if I’m leaving out important context. I urge you to do that. Also, my quotes are longer, more able to be interpreted independently.

An out-of-context short quote: Richard Rorty

The American philosopher Richard Rorty doesn’t play much of a role in the book, possibly because he’s harder to make into a nut. (His writing is relatively clear and jargon-free by academic standards, and – on the page – he comes across as a nice guy.) However, one use of his book, Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity (1989) Free online version, the introduction alone as a PDF makes a good example because I’ve actually read it. I can compare what Kimball says it says to what it says.

Kimball writes the following. I have bolded what he quotes of Rorty.

“[C]onsider, as another example, Richard Rorty’s endorsement of a ‘postmetaphysical’ and ‘postreligious’ culture in which ‘the sermon and treatise’ are being replaced by ‘the novel, the movie, and the TV program’ as the ‘principle vehicles of moral change and progress'.” (Kimball, p. 158, citing Contingency, pp. xiii-xvi, which is the entirety of the introduction.)

What a nut!

But those quotes are suspicious. Here they are, separated from Kimball’s words:

- ‘postmetaphysical’

- ‘postreligious’

- ‘the sermon and treatise’

- ‘the novel, the movie, and the TV program’

- ‘principle vehicles of moral change and progress’

Kimball joins these snippets to misrepresent Rorty, whose explicit goal is to think about what it means to be a “liberal ironist.” I rather like Rorty, but he has a positive gift for inventing terms that convey nothing when you first read them. Maybe that’s a good thing. Rorty’s introduction defines the term:

-

An “ironist” is someone who accepts that his own most central beliefs and desires are not provable but also accepts he can’t simply cease believing them. Traditionalists like Bloom and Kimball tend to think relativism is the slippery slope to complete nihilism. Rorty says naw, people don’t work like that.

-

A “liberal,” to Rorty (following Judith Shklar), is someone who believes “cruelty is the worst thing we do.”

In sum:

“Liberal ironists are people who include among [their] ungroundable desires their own hope that suffering will be diminished, that the humiliation of human beings by other human beings may cease. [But] for liberal ironists, there is no answer to the question ‘Why not be cruel?’ – no noncircular theoretical backup for the belief that cruelty is horrible.” (Contingency, p. xv)

But people sure are cruel a lot of the time. How do you get people to believe and act on the proposition that cruelty is horrible?

“It is to be achieved by […] the imaginative ability to see strange people as fellow sufferers. […] This is a task not for theory but for genres such as ethnography, the journalist’s report, the comic book, the docudrama, and, especially, the novel. Fiction like that of Dickens, Olive Schreiner, or Richard Wright gives us details about kinds of suffering being endured by people to whom we had previously not attended. Fiction like that of Choderlos de Laclos, Henry James, or Nabokov gives us the details about what sorts of cruelty we ourselves are capable of, and thereby lets us redescribe ourselves. That is why the novel, the movie, and the TV program have, gradually but steadily, replaced the sermon and the treatise as the principle vehicles of moral change and progress.” (p. xvi, my emphasis.)

Rorty hopes for a “postmetaphysical” and “postreligious” culture because he believes metaphysics and religion haven’t worked, that sympathetic imagination is a better bet for a better world.

You may disagree, but it’s not nuts. And Rorty is drawing from Western tradition. At least, Adam “invisible hand” Smith expressed what seems to me a similar conclusion. Smith is all about how sympathy (empathy) acts to produce “benificent ends” more effectively than the “the slow and uncertain determinations of our reason.” Those ends are what the “the great Director of nature intended [emotions and self-interest] to produce” And it’s hard to square with Kimball’s claim that people like Rorty are after what he (Kimball) described as “a radical social transformation.” At least, I hope less suffering wouldn’t be seen as some sort of fundamental transformation of the United States.

Kimball’s choice of what to quote is clever in how it ties back to his earlier text. Prior to discussing Rorty, Kimball has given examples of academics dealing with the frivolous and modern, such as teaching seminars on “the movies of Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy” (p. xiii) or publishing books on MTV:

“In Rocking Around the Clock, Professor Kaplan enumerates the five types of rock video she has discerned in the course of her painstaking research into MTV and provides recondite analyses of such landmark works of art as ‘Smokin’ in the Boys’ Room,’ by the rock band Motley Crue [sic], ‘Rebel Yell,’ by Billy Idol, and John Cougar Mellencamp’s ‘Hurts So Good’ […]” (p. 44)

So, I’d argue that Kimball’s reader is primed, by page 152, to read “the novel, the movie, and the TV program” as meaning similarly frivolous works. But that’s not in fact the case. Rorty discusses respectable novels by people like Proust, Orwell, and Nabokov. He uses Dickens to support his claim of the importance of literature to the reduction of cruelty: “his novels were a more powerful impetus to social reform than the collected works of all the British social theorists of the day.” (Contingency, p. 147)

Rorty is not frivolous, but Kimball uses selective quotation to make him appear so.

In Kimball’s 1998 edition (online text), he makes his attack on Rorty even more unfair:

“Indeed, [Rorty] looks forward to a time when philosophy as a distinct discipline will have disappeared altogether, and he aims to hurry its demise by ‘blurring the literature-philosophy distinction and promoting the idea of a seamless, undifferentiated “general text”,’ in which, say, Aristotle’s Metaphysics, a television program, and a French novel might coalesce into an exciting object of hermeneutical scrutiny.” (pp. 2-3)

He again cites Rorty’s introduction, but notice the changed quote:

‘blurring the literature-philosophy distinction and promoting the idea of a seamless, undifferentiated “general text”’

These words do not appear on the cited pages. In fact, although archive.org’s search function is imperfect, I don’t find the words “seamless,” “general text,” or “undifferentiated” anywhere in the book. “Blurring” appears once, on page 32, where Rorty says Freud is “blurring the prudence-morality distinction.

This is disappointing in a book that celebrates Matthew Arnold’s description of the humanities as offering “the best that has been thought and written” specifically because “intellectually, its aim was truth; morally, its aim was virtue” (p. 39) and faults today, “when such value judgments are looked on with suspicion.” (ibid.)

Note also how Kimball has replaced Rorty’s actual words “the novel, the movie, and the TV program” with a suggestion of specific works Rorty combined (would approve of combining?) into what Kimball describes, sarcastically, as an “exciting object of hermeneutical scrutiny.”

Kimball is implying Rorty scrutinizes such mashups. Rorty doesn’t. Although Kimball doesn’t directly attribute “exciting object of hermeneutical scrutiny” to Rorty, I want to point out that Contingency contains only one use of any variant of “hermeneutic,” in a quote from someone else. As Kimball has a great deal of scorn for users of five-dollar words like “logocentric”, “phallocentric”, and “signifier,” attributing a word to Rorty that he doesn’t use helps establish a sub rosa connection: Rorty’s a nut, like all those others.

Summaries and vibes

It’s hard to approve of an idea when it’s associated with other ideas you disapprove of, or was proposed by someone you dislike. That makes it relatively easy to guide a reader away from an idea, not by engaging with the argument, but by associating the idea with… negative vibes.

Because this post is rather long, I’ll give only one example. I’ll introduce it with something that happened to me.

Except in Sweden, I don’t meet many women taller than me (I’m 5’11” or about 180 cm), but I once worked with one who was noticeably taller. One day, she told me always hangs back when following another woman to a bathroom because “it makes women nervous to have someone big looming up behind them.” That had never occurred to me before, and I realized I unthinkingly loomed behind smaller women. Which further made me realize (once again) that I basically go through life thinking myself safe, a being both unthreatening and unthreatened. So I unthinkingly tend to believe that, sure, everyone feels the same way, right?

Turns out not.

If you want to be fancy, you could say I’d “defamiliarized” my own experience by realizing it’s not so universal. By realizing how unfamiliar my experience might be to other people, I made it a little bit unfamiliar to me.

Now let’s look at how Kimball expresses much the same idea, but in a way that provokes the reader’s incredulity.

The passage in question is on page 18. There’s some preparatory work associating the word “feminism” with other scare words and intimations of a grand plot:

“Behind the transformations contemplated by the proponents of feminism, deconstruction, and the rest is a blueprint for a radical social transformation.” (p. xviii)

“[T]he single biggest challenge to the canon as traditionally conceived [is] radical feminism.” (p. 15)

“Blending a deconstructionist’s obsession with language and a feminist’s obsession with male dominance […]” (p. 16)

“Feminism cannot rest content with championing female (one could hardly call it feminine) experience.” (p. 18, just before the passage quoted below.)

Kimball is drawing anecdotes from a one-day symposium at Yale’s Whitney Humanities Center to “examine the subject of literary theory and the curriculum” (p. 10). The second session “was devoted to the literary canon and anticanonical criticism” (p. 16). Its first paper was presented by “Elaine Showalter, chairman (or rather, chairwoman) Snark is an important part of the anti-PC style. I’ll show some examples later. […] who has achieved a position of great power and influence in the academy” (ibid).

Showalter’s paper is described, as is typical, by a set of short quotes attributed to her – “a transformation of the curriculum,” “gender as a fundamental category of literary analysis,” “a female vernacular”, and “women can name their own experience” – separated with Kimball’s reaction-shaping phrases like “nothing less than the triumph of feminist ideology over literature” (all phrases from pp. 16-17).

There follows some snark about women’s studies programs, and about the idea that bingeing and purging as something too many women do might reveal something about the life and poetry of Sylvia Plath. Some context might be relevant. The “New Criticism,” which dominated American literary criticism after World War II, was dead-set against using the life of the author in the interpretation of the work. The work had to be analyzed in isolation. Whether the author was bulimic is irrelevant. The New Criticism was a conscious break with earlier styles of criticism, which would use the author’s life history and issues in the society around him to help explain the meaning of the work. Kimball only mentions the New Criticism in passing, but he does speak scornfully of the New Historicism, which is in some sense a resurrection of those earlier, biographical styles. So a commitment to the New Criticism might account for some of Kimball’s incredulity at the thought that Plath’s life might help in understanding, say, her poem “Daddy.” He’s of the right age to have been steeped in the New Criticism (as I, six years younger, was for my 1981 English Literature BA). This is further preparatory work, setting the reader up to react by rolling his eyes and thinking, “there they go again.”

Here at last is the quotation in question:

“Professor Showalter named ‘the defamiliarization of masculinity’ as ‘one of the most important tasks facing feminist criticism in the next decade.’ If male experience has hitherto been understood to be natural and unproblematic, a mode of experience that represents ‘humanity in general,’ it must now be exposed as a biased ideologically laden construction. Men, too – perhaps especially men – must be enlisted in this attempt to ‘open up the discourse of masculinity.’ And good news: for those men who have abandoned ‘the myth of objectivity and transcendence,’ who have ‘the courage to become vulnerable’ and ‘realize that they are embodied,’ this new recognition of masculinity ‘will be a transformation of volcanic force.’ ‘Simply to think about masculinity is to become less masculine oneself’ we were assured – and, after all, what could be better than that?

It must not be thought that such ideas are considered aberrant or especially radical in the academy today – quite the contrary. (p. 18)

You, the person reading this, have been presented with two descriptions of “defamiliarization” and its results. Both Kimball and I used some rhetorical tricks to be more persuasive.

-

I presented a story of my own, using deliberate, moderate language. I made sure to play down grand claims: I had an experience. It was atypical for a man, as it happens. I learned something. In this way, I aimed to prepare you to think of “defamiliarization” as a deliberate, moderate idea. Note also that I didn’t lead with the jargon word, but only later used it to label an experience I’d shared. And I prefaced the word with a “just folks” clause: “If you want to be fancy, you could say I’d ‘defamiliarized’ my own experience.”

I also presented my story before his. If you were unfamiliar with the idea of “defamiliarizing masculinity,” I wanted to – um – familiarize you with it as being unthreatening, so as to make Kimball’s reaction seem much ado over not much.

-

Kimball presents a story about a person who is identified as a leading representative of a movement he scorns (nutpicking). He’s set up the expectation in the reader that they’re about to read something ridiculous (argument from incredulity). He uses heightened language (“exposed,” “abandoned”). He makes the results of accepting Showalter’s suggestion seem catastrophic. You’re to be made “less masculine,” which requires you to “abandon the myth of objectivity” and think of your life thus far as being an “ideologically laden construction.”)

Evidence shows that Kimball’s style of histrionic rhetoric is more effective. He got paid to write two more editions. I do not expect anyone to pay me to write a new revision of this blog post in 2030, and then again in 2040.

Shibboleths

Wikipedia says that “a shibboleth is any custom or tradition, usually a choice of phrasing or single word, that distinguishes one group of people from another.” Here’s its history, from the Bible (Judges 12:5-6):

And the Gileadites took the passages of Jordan before the Ephraimites: and it was so, that when those Ephraimites which were escaped said, Let me go over; that the men of Gilead said unto him, Art thou an Ephraimite? If he said, Nay; Then said they unto him, Say now Shibboleth: and he said Sibboleth: for he could not frame to pronounce it right. Then they took him, and slew him at the passages of Jordan: and there fell at that time of the Ephraimites forty and two thousand.

If you want to deepen one of your fellows' dislike of a stranger, an excellent way is to point and say, “He talks funny.” Weird but true.

Kimball does this. Humanities professors of the generation Kimball dislikes use funny words (“logocentrism”) and write in convoluted ways. Of course, singling them out for convoluted text is odd. Here’s the first sentence of Montaigne’s third essay, as translated in 1877: I did cherry-pick this sentence from among Montaigne’s opening sentences: he did write shorter ones. But it only took me three tries to hit pay dirt. A 1958 translation is somewhat more clear to the modern reader because it uses parentheses and dashes instead of an endless succession of commas.

“Such as accuse mankind of the folly of gaping after future things, and advise us to make our benefit of those which are present, and to set up our rest upon them, as having no grasp upon that which is to come, even less than that which we have upon what is past, have hit upon the most universal of human errors, if that may be called an error to which nature herself has disposed us, in order to the continuation of her own work, prepossessing us, amongst several others, with this deceiving imagination, as being more jealous of our action than afraid of our knowledge.”

Kimball would be an odd traditionalist if he didn’t hold Montaigne in the highest esteem, yet that ancient’s convoluted style doesn’t strike me as wildly dissimilar from, say, Derrida or Foucault, two modern Frenchmen whose style Kimball mocks.

I’ve been arguing that Kimball doesn’t engage with the substance of what his opponents profess. Rather, he presents their ideas as inherently ridiculous. My argument here is that he goes beyond mocking ideas. His argument frequently relies purely on the equivalent of a Gileadite pointing at an Ephraimite and saying, “He talks funny.”

A favorite way to do that is to point at titles like these:

- “Relevance of Theory / Theory of Relevance”

- “From the Theory of Reading to the Example Read”

- “Of Mimicry and Man: the Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse”

- “On the Eve of the Future: The Reasonable Facsimile and the Philosophical Toy”

- “Next-Level A/B Testing: Repeatable, Rapid, and Flexible Product Experimentation”

Oops. My mistake. That last is a book from the Pragmatic Bookshelf.

The purpose of a title is threefold:

- To be something of a summary of an argument that you, as its author, sure hope can’t be fully captured in a single sentence.

- To catch the attention of someone who might want to read it.

- To hint to someone who won’t be interested that they shouldn’t bother even reading the abstract, introduction, or back-cover copy.

Beyond that, different fields have different conventions for titles. Some of those conventions don’t have particularly strong reasons behind them. They accreted in a series of accidents. Here are two titles of papers my wife coauthored:

-

“Effects of flunixin meglumine and local anesthetic on serum cortisol concentration and performance in dairy calves castrated at 2 to 3 months of age”

-

“Prepartum intake, postpartum induction of ketosis, and periparturient disorders affect the metabolic status of dairy cows”

I find both mildly humorous. “It’s so important to warn off people only interested in calves castrated after three months of age that you put it in the title?” Or: “Yeah, I expect the paper wouldn’t be published if those things didn’t have an effect. Maybe you should say whether the effect is good or bad, up there in the title?”

But it would be dumb for me to judge medical papers based on their titles or whether they use fraught jargon. Kimball encourages people to do just that.

Pointing and laughing goes together with shibboleths like peanut butter goes together with chocolate, and so Kimball’s book drips with snark. Some of it’s pretty good:

“If the issue is architecture considered as a ‘physic,’ I suppose one could admit that there is something emetic about this passage.” (p. 125)

Kimball reports on a conference panel session where Jacques Derrida says, in Kimball’s account: “A great deal of money is being given to the sciences, while the humanities, having to make do with far more meager amounts, are in danger of being ‘marginalized’” (p. 177). And then Kimball tosses out a zinger:

“At least when it came to talking about money, Professor Derrida abandoned his customary intellectual high jinks and was perfectly straightforward. There was no attempt to make a lack of money seem like an abundance, or to show that the ‘margins’ of this kind of ‘discourse’ were really the center.” (also p. 177)

(It’s funnier if you’ve read some deconstructive criticism.)

Some of the snarks are groaners. When discussing an article by Geoffrey H. Hartmann defending Paul de Man, the disgraced Sterling Professor of Humanities at Yale, Kimball writes:

“[T]he balance of the piece attempts to rehabilitate Professor de Man by viewing those writings through the lens of deconstruction. The result is a sterling – if not a Sterling Professor’s – example of vindication by obfuscation.” (p. 107)

The sheer amount of snark, though, became oppressive to me. I don’t much care for using adjectives as verbs, but really, he’s clearly acting to “other” a whole lot of people by one of the most effective ways: ridicule. We’re in the land of “us” vs. “them,” tribe vs. tribe.

He also plays the old propagandist’s trick of making the enemy simultaneously strong and weak. As an anonymous someone said, “I love the carefully intertwined urban legends in which antifa are dangerous radicals coming to shoot your livestock and trash your community but also limp wristed colorful haired gender nonconforming soyboys and girls who couldn’t possibly pose a physical threat.”

To Kimball, the humanities professorate is simultaneously intent on “radical social transformation” and hopelessly frivolous fashion-followers. He uses the word “fashion” a lot, but I think his use of “chic” shows how committed he is to the characterization:

“What any of this could possibly mean was never revealed, but no one seemed to mind: it all sounded so exquisitely chic.” (p. 16)

“[W]hat is chic at Harvard one semester is sure to be aped at the state school or aspiring liberal arts college down the road the next.” (p. 27)

It is in the pages of such journals that the latest personalities, chic theories, and critical vocabularies are auditioned and, if found acceptable, are trotted out over and over again until they become verbal tics.” (p. 77)

That this paragon of chic academic achievement [Paul de Man] should stand revealed as the author of anti-Semitic articles […] (p. 103)

“a theory and practice of architecture motivated largely by various ideas and catchphrases appropriated from chic literary theory.” (p. 119)

“long before [architect Philip] Johnson had given up modernism to become the chief impresario of postmodernist chic […]” (p. 134)

[T]his cadre of chic theorists and literary activists […] (p. 146)

Strange creatures, these professors with their simultaneous “defiant hermeticism and gratuitous triviality” (p. 57). I am perhaps unfair. It may not be that the professors are so strong but that students are so weak and gullible. This has echoes of Bloom’s attitude. Kimball describes a professor’s proposal for “teacher swapping […], an innovation in which one teacher teaches a course for, say, five weeks, after which another comes in and begins by asking what the first teacher said, probing his presuppositions and prejudices” (p. 22). That actually seems like a neat idea to me. Kimball’s reaction is that it’s “a prescription for confusion, guaranteed to muddle young minds” (ibid). To him, the proposal ignores that “some intellectual positions might be truer or more worthy of transmission than others” (ibid). For any topic in the curriculum, the “proper business of the university” (ibid.) is to find the right answer and tell it to the students.

To rally your team, it helps if the enemy is both frightening (thus important to fight) and ridiculous (thus beatable).

Reverse nut-picking

A problem with nut-picking is that the reader might wonder: sure, this person is a nut, but do they represent a broader – therefore dangerous – coalition? Maybe they’re not important? Maybe I shouldn’t care?

One good way to show they are important is to show them getting the acclamation of their peers:

“It need hardly be said that the audience was spellbound by Professor Baker’s performance.” (p. 20)

“It has become rare in these quiet days in the academy that your average white, middle-class audience can indulge in such ecstasies of intellectualized liberal shame, and they were clearly grateful to Professor Baker for an opportunity to gorge themselves on it.” (p. 21)

“Naturally, this provoked considerable mirth in the audience, for who in the academy still believes in either the West’s achievements or its honesty?” (p. 25)

Note how early these three quotes come in the book. The “othering” message needs to be given early and often.

Where do we stand, here in 1990?

“Politically correct” had not really taken off in 1990, though Kimball used the phrase five times. That is about to change. Per Wikipedia, the Lexis news service recorded 70 citations in 1990, but there will be 1,532 in 1991 and more than 7,000 in 1994.

Kimball marks a shift from academics criticizing the academy from the inside Bennett was an outsider, but he gathered up academic insiders – tenured nonradicals – for the three workshops that led to his report. Bloom had spent his career as a professor. to attacks from the outside. That will be the norm from now on.

This insider/outsider split probably contributes to the positioning of the good guys (the author’s readers) as being in an intrinsic battle with the bad guys (the academics), and to an “all’s fair in love and war” attitude.

So, with Kimball, the rhetorical tricks have become more blatant. The need to win is becoming more important than scholarship, fairness, or truthfulness: we’re now in the political arena, not the academic, and the power to effect change is what matters. Kimball might respond that “they started it!” Maybe so, but my project here is to look at anti-PC rhetoric.

Winning means conjuring up the right emotions in the reader, so that the reader will lend their political power to the counter-reformation. (Humanities professors are not to be persuaded. They are to be fixed or removed or defused.)

In Bloom and Bennett, the students were part of the problem. In Kimball, they are now more in the role of victims, but not many words are spent on their plight. They’re more passive vectors: transmitters of wrong ideas from within the lecture hall to the society at large. (Kimball does mention censorship and what will come to be called “speech codes,” but those will only take the spotlight in 1991.)

There is a sort of scope creep. Disagreements about things like literary interpretation or how important it is to teach “the best that has been thought and said” (Matthew Arnold) are now more explicitly a stand in or synecdoche for larger social issues: the role of women, gay rights, America’s continuing problem with race, and so on. Because an intellectual dispute has been divided into two sides, there’s an increasing amount of “whatever they’re for, we’re against.”