test

Author’s note: This is an essay that does a “close reading” of a particular essay that critiques deconstruction. A valid objection is that I have devoted a lot of effort to an essay that probably wasn’t intended to be a finely-honed, final statement of someone’s opinion.

However, I think it’s still worthwhile, because it illustrates something literary-style criticism is for: you’re reading along in something when an oddity brings you up short. What, you wonder, is that doing here? Criticism provides tools for generating hypotheses about that. This essay uses the critical technique called “structuralism” (explained below) to speculate about the “huh?” moments in the essay.

Contents

- Oddities

- Structuralism

- The clever peasant

- Odysseus' journey

- Structuralism and egregores

- Political correctness

- Audiences and aims

Oddities

In 1993, the software engineer Chip Morningstar published an essay called “How To Deconstruct Almost Anything.” I recommend you read the essay now – it’s not long – and note down any oddities you discover. I’ll wait…

Here’s some of the larger oddities (I’ll mention others later):

-

Why is the opening story there? Is it believable? I think not. While I’ve no reason to doubt Morningstar perceived himself as being a big hit with the whole audience – not just some or all of the “techies” – I’m sure many of the professors reacted the same way lawyers do when a new client offers up “Why don’t sharks attack lawyers? Professional courtesy” or waiters do when a customer responds to “Hi, I’m Brian, I’ll be your server tonight” with “Hi, I’m Homer. I’ll be your customer tonight.” With rolled eyes.

A newbie’s fresh and clever take is often old hat to the pros. Much of the jargon Morningstar mocks predates anything that could be called “deconstruction” or “postmodernism.” Derrida and deconstruction hit the big time in 1967, and Derrida was making up weird new jargon from the very start: “free play,” “the supplement,” and the notorious play on words “différance.” And, at the time of Morningstar’s essay, people had been making fun of that jargon for over two decades. American philosopher John Searle’s 1983 review of Culler’s On Deconstruction is an example. (There’s a paywall, but the text is also available here.) Not only does Derrida make up jargon, the jargon is often “cleverly” punny, refers back to non-current meanings of the words, is self-referential, and so on. There’s a justification for it: he’s trying to write about what writing can’t do, which is vaguely like negative theology, which holds that God’s nature lies beyond description, so one can only grasp it by something akin to a proof by contradiction: you approach what God is by enumerating what He is not. But I think Derrida overdoes it. And, in something like the way jazz saxophonist and heroin addict Charlie “Yardbird” Parker’s example prompted a heroin fad among musicians – “If you wanna blow like Bird blew, you gotta do like Bird did” – academics followed Derrida’s lead. They may have also followed the example of his prose, which even his translator (of Writing and Difference) described as “dense and elliptical” but defensively notes that “however syntactically complex or lexically rich, there is no sentence in this book that is not perfectly comprehensible in French-with patience.” (p. xiv) Good to know. Therefore, I just don’t believe the butts of the joke were “on the floor in hysterics” or even that some “obtuse English professor” smiled wryly, acknowledging he’d been pwned.

-

One of Morningstar’s points is that professors get “points” with rhetorical tactics that “would be frowned upon in engineering or the sciences,” including “appeals to authority.” That’s after he opens the essay with an appeal to authority: its epigraph is ‘“Academics get paid for being clever, not for being right.” – Donald Norman.’

He also writes that professors believe “politics and cleverness are the basis for all judgments about quality or truth, regardless of the subject matter or who is making the judgment.” (Bold font is my emphasis throughout.) If the “who” matters to making the judgment, I don’t see any way in which that person isn’t an authority – to whom you must be appealing by mentioning them.

OK, two small self-contradictions. More importantly, the entire essay is an appeal to authority: Morningstar’s. The essay contains not a single quotation from the people he is critiquing. How do we know they favor “style and wit rather than substance?” Morningstar tells us. How do we know their politics shows through? Morningstar tells us. He provides claims, not evidence. How do we know “occasionally a Professor of Literature will collaborate with a Professor of History, but in academic circles this sort of interdisciplinary work is still considered sufficiently daring and risqué as to be newsworthy”? Morningstar tells us, despite having just described his experience at “an aggressively interdisciplinary gathering, drawing from fields as diverse as computer science, literary criticism, engineering, history, philosophy, anthropology, psychology, and political science.”

-

The essay is ~4230 words long. The beginning anecdote consumes 20% of the words. Only 40% is devoted to the nominal topic: “How to Deconstruct Almost Anything.” 27% is devoted to what’s wrong with the academic humanities. That latter topic bookends the meat of the essay, and indeed is the closing topic. Is this essay really about deconstruction?

-

Morningstar compares the academic humanities of 1983 to that of 1993 and claims that it had “experienced a considerable amount of evolution (or perhaps more accurately, genetic drift) since then.” His diagnosis is what we nowadays call “epistemic closure": “Professors of Literature or History or Cultural Studies in their professional life find themselves communicating principally with other professors of Literature or History or Cultural Studies” and “Decisions about their career advancement, tenure, promotion, and so on are made by committees of their fellows.”

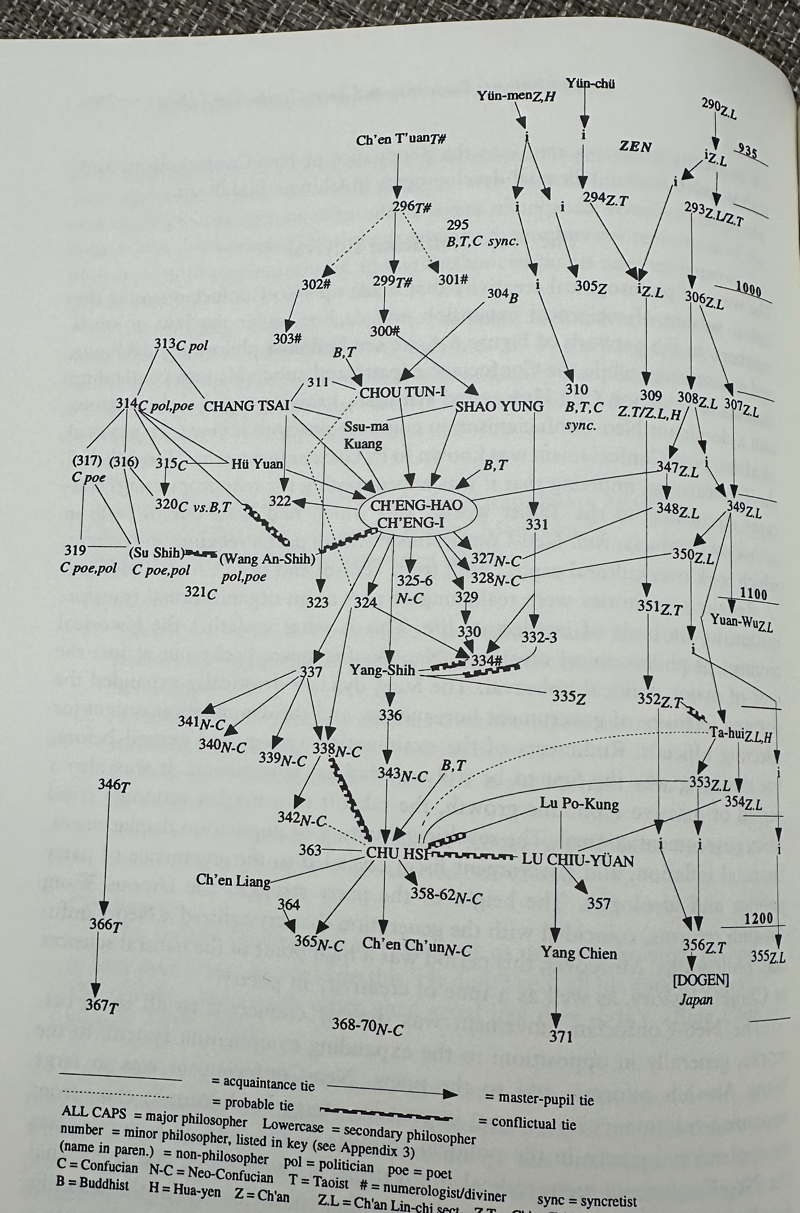

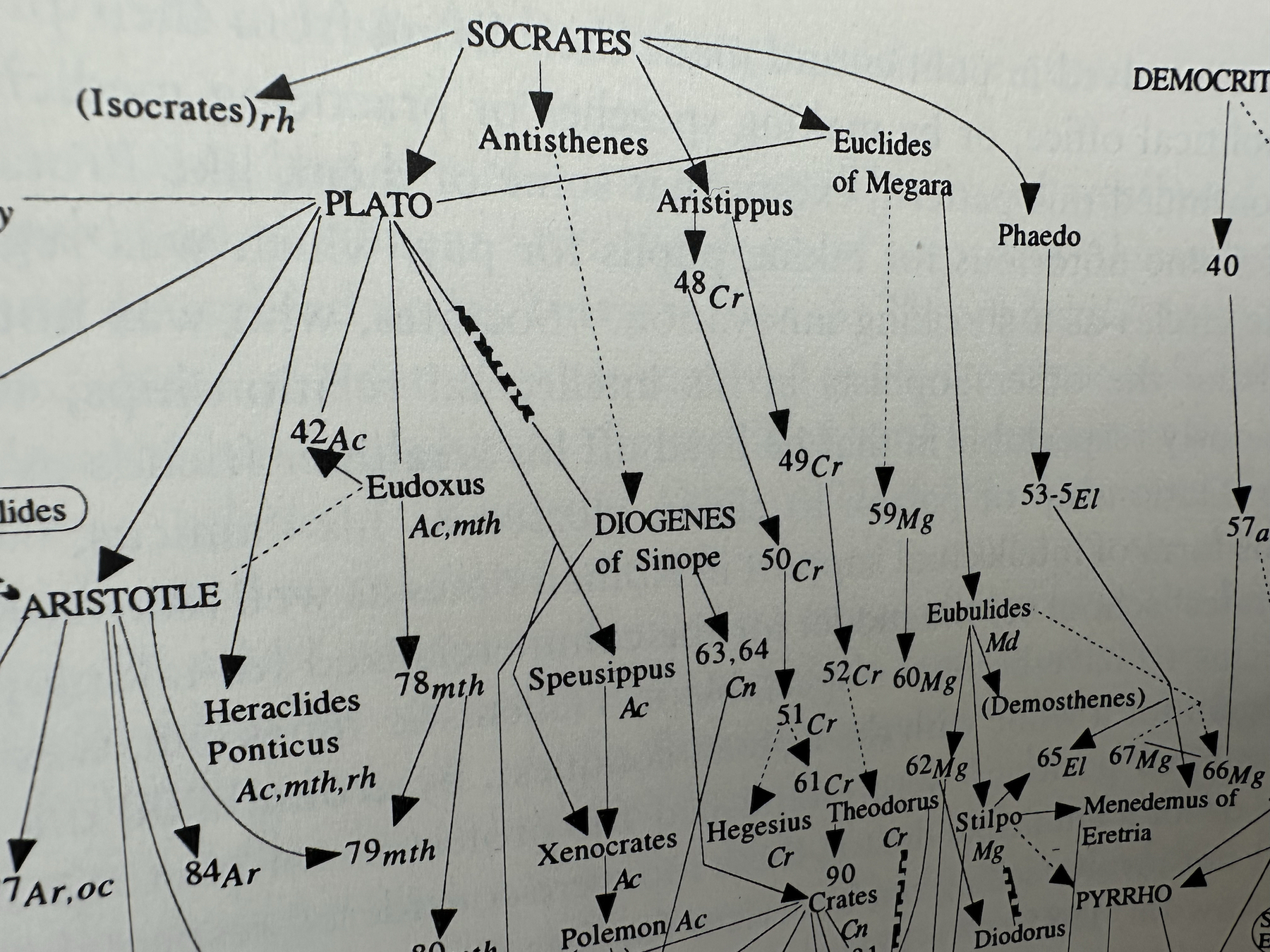

But promotion and communication patterns were the same in 1983. (Communication patterns have been the same since, well, forever.) In his The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change, Randall Collins claims these communication patterns are a main engine of intellectual work. He traces them back to the very beginnings of philosophy. See the images below or here and here.

What caused the “genetic drift” since then? Why is something that hasn’t changed blamed for a change?

-

The essay ends with a call to arms: “It is clear to me that the humanities are not going to emerge from the jungle on their own. I think that the task of outreach is left to those of us who retain some connection, however tenuous, to what we laughingly call reality. We have to go into the jungle after them and rescue what we can.”

Why? There’s the old story about the child who gets a pile of dung for Christmas but is cheerfully optimistic: “With all this manure, there must be a pony somewhere!”. Morningstar’s already dug through the dung and found “some content, much of it interesting.” But “the field is absorbed in triviality.” And the verbiage is “right off the bogosity scale, pegging my bogometer until it breaks.” When it comes to the actual application of the theories to literary works, “most of it [is] highly questionable.”

This is not exactly rousing stuff. What reader wants to wade into the dung on the off chance of finding a pony that Morningstar missed? The quoted text is ambiguous as to whether it’s the humanities or humanities people or some content that is to be rescued. It’s the humanities that will not “emerge on their own.” “But we will go after them” could mean “to retrieve them” or “follow the trail they blazed (so imperfectly).” Since what’s being rescued is called a what, I think it’s humanities concepts being rescued rather than people (as a “mind stretching departure from debugging C code”). Anyway, nothing in the rest of the essay indicates the professors want or deserve to be rescued. They’re a pretty useless bunch.

Structuralism

Morningstar suggests that the reader deconstruct his (Morningstar’s) essay. I don’t find that particularly revealing or interesting, so I’ve chosen a different tool from the intellectual toolbox. For a deconstruction, see a companion piece, which also explains why his description of deconstruction is only OK.

Structuralism is a form of analysis that assumes human behavior reflects shared structures inherent to either the human mind or to society in much the way that a correct C program reflects the syntax of the C programming language. Humans elaborate – sometimes in very complex ways – on underlying structures.

For structuralists, the most popular structure is the simple “binary opposition.” Structuralists mean the same thing by the phrase as deconstructionists; it’s just that they use the concept differently. Deconstruction’s origin story centers on a 1966 talk by Jacques Derrida. It was at a conference on structuralism. Derrida’s message was “What you’re trying to do won’t and can’t work. Any interpretation you construct using binary oppositions I can deconstruct (get it? get it?) using the same binary terms. Here’s why.”

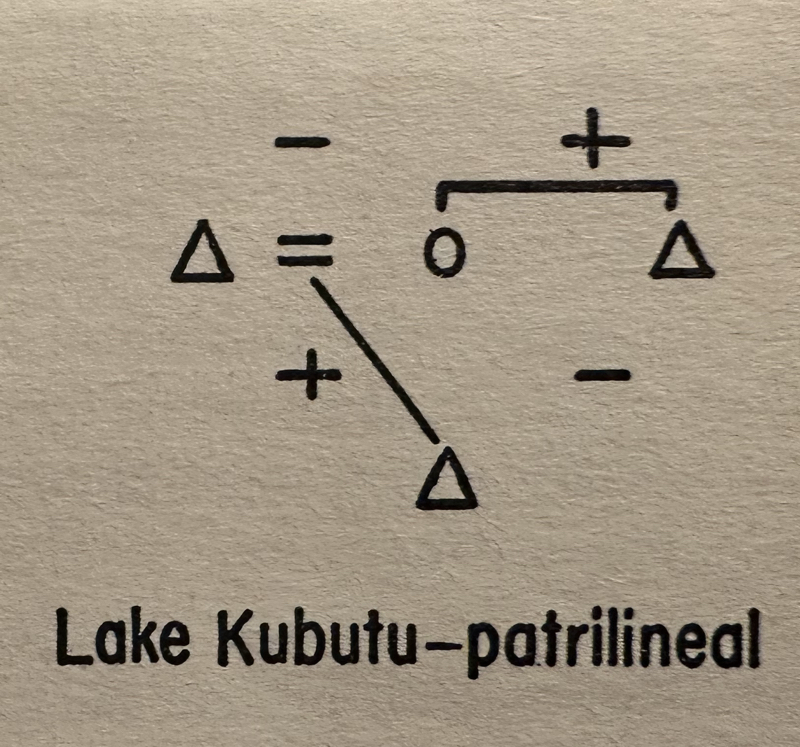

From Claude Leví-Strauss, Structural Anthropology, 1963 (in the English translation), chapter 2, p. 45.However, there are other structures. For example, the anthropologist Claude Leví-Strauss believed that, in societies where marriages were arranged by one male giving a sister or daughter to another, kinship relationships had, as their “atom,” a structure made up of the father, the son, the son’s sister, and the son’s maternal uncle. See the margin for an example.

Leví-Strauss had noticed that, to oversimplify, if the son’s societally-mandated relationship to the father was, let’s say, uneasy, his relationship to the maternal uncle would be warm and friendly. Or it could be the other way around. Also, if the society was such that brothers and sisters were not allowed to be under the same roof, relations between husband and wife would be warm. In contrast, if husbands and wives lived separately, with the husband only seeing the wife when he snuck into her quarters (presumably for sex), the brother and sisters might have such warm relations that they not only lived under the same roof but slept in the same bed. Between the four people, only four out of the possible sixteen antagonistic vs. supportive combinations ever happen. A given society will have one of those atoms as its building block for more complicated kinship systems.

For my purposes, I’m interested in the structures underlying stories and other narratives. An example of this sort of thing is Vladimir Propp’s 1928 analysis of Russian fairy tales. He claimed they were composed of a subset of 31 basic structural elements. He calls them “functions,” but I think of them as plot points or events.

Not that every (maybe any) folk tale used all of them, but every folk tale used some of them, and they always appeared in a fixed order. For example, if “Reconnaissance” (where the villain seeks out knowledge to support their scheme) occurs, there cannot be a later “Interdiction” event because Interdiction always precedes Reconnaissance if it appears at all.

My claim here is that Morningstar’s essay is usefully understood as being shaped by three story structures:

- The clever peasant.

- The hero’s journey (Odysseus subtype).

- The polemic against “political correctness,” which by 1993 had developed its own “atoms” that different authors, including Morningstar, recombined.

The clever peasant

There are many shorter fairy tales in which someone who’s lowly and has little power (a peasant or a tailor, say) outwits someone powerful and highborn and makes a fool of them:

- In “The Peasant and the Devil,” a peasant tricks a devil into saying he’ll give the peasant gold if he can have half the crop for two years running. The first year the peasant plants beets – he gets the half under the ground and the devil gets the (useless) half above ground. The second year, the devil demands the half below ground, so the peasant plants wheat.

“When the Devil came, he found nothing but the stubble, and went away in a fury down into a cleft in the rocks. ‘That is the way to cheat the Devil,’ said the peasant, and went and fetched away the treasure.”

- In “The Clever Peasant,” the titular peasant bets his friends he can have lunch with the notoriously standoffish ruler. He succeeds with trickery, and then:

“The lord flew into a rage. He turned bright red and shrieked and yelled and cursed. ‘Get out of my house, you fool!’ he shouted.

“The peasant looked him steadily in the eye and replied, ‘I am not a fool, my lord. I’ve had an excellent meal and a good laugh at your expense. What’s more, I’ve won three sacks of wheat and two bullocks from my friends. A fool could not have done all that.’ And he walked out of the lord’s house, a big grin on his face.”

Morningstar’s introduction to his essay establishes him (“a vulgar engineer”) as the clever peasant, using words to mislead professors:

“At first, various people started nodding their heads in nods of profound understanding, though you could see that their brain cells were beginning to strain a little.”

But, the trickery of course has to be revealed to the victims, else it’s no fun and there’s no story:

“Then some of the techies in the back of the room began to giggle. By the time I finished, unable to get through the last line with a straight face, the entire room was on the floor in hysterics, as by then even the most obtuse English professor had caught on to the joke.”

One imagines Morningstar having “a big grin on his face” when “with the postmodernist lit crit shit thus defused, we went on with our actual presentation.”

The clever peasant story does more than laud a person who’s assumed lowly but is actually superior. In building up the peasant, it tears down their opponent, who is revealed as high in status but deficient in brains. Not just not clever, but downright stupid.

The story has the effect of getting Morningstar’s readership (surely almost exclusively techies) on his side – we cheer his trickery. And it positions the professors as stupid, not (as might otherwise be assumed) as serious scholars speaking in their own jargon, meaningful to them.

Odysseus' journey

The subtitle of the essay is “My Postmodern Adventure.” Thus prompted, I realized I could make a rough correspondence between Morningstar’s essay and Odysseus' voyage in the Odyssey. Let’s step through it to see similarities and deviations.

The start of Odysseus' story tells of him coming up with the idea of the Trojan Horse, establishing him as clever. (He is, in fact, omni-competent: excelling others as a thinker and a fighter and a lover.) Morningstar’s conference prank plays the same role. However, the character “Morningstar” has to transition from a peasant to someone who can speak with authority. (Even clever peasants are low status, and they’re not presented as being deep thinkers or being people their fellow peasants can trust. For example, the Clever Peasant tricks both his ruler and his friends.) Echoing the structure of a heroic epic, with Morningstar as the hero, implements that transition. (The reader has been trained how to respond to such stories.)

The story of the Trojan Horse is told in the third person (at the end of Part 8), but then the Odyssey switches to the first-person in Part 9. It’s Odysseus who’s speaking. In case you missed his cleverness, Odysseus reminds you:

“I am Odysseus son of Laertes, renowned among mankind for all manner of subtlety, so that my fame ascends to heaven.”

Now, forthright boasting of this sort was expected of strongmen in Bronze Age heroic cultures like the Archaic Greeks. Our style today is the humblebrag:

“Being a vulgar engineer I’m allowed to break a lot of the rules that people in the humanities usually have to play by, since nobody expects an engineer to be literate. Ha.”

“I can’t claim to be an expert, but I feel I’ve reached the level of a competent amateur.”

Odysseus is trying to come home from an adventure, whereas Morningstar chooses to go on one:

“Afterward, however, I was left with a sense that I should try to actually understand what these people were saying, really.”

Both receive aid from people otherwise not involved in the story. Odysseus gets a bag of winds; Morningstar gets a book recommendation: Cullen’s On Deconstruction.

However, the going isn’t easy. Odysseus keeps being let down by his men doing stupid things, and – step by step – they all get themselves killed. Meanwhile, Odysseus solves all the problems he and they confront using a combination of cleverness and violence. The cleverness is highlighted, described in more detail than the violence.

Morningstar doesn’t have a crew – he works alone from the very beginning – but also overcomes great difficulties:

“I got the book and read it. It was a stretch, but I found I could work my way through it, although I did end up with the most heavily marked up book in my library by the time I was done.“ I sympathize. I’ve read Cullen too. Nowadays, I’d recommend either Beginning Theory or Critical Theory Today: a User-Friendly Guide, which are written much more straightforwardly. I don’t think any such “interested amateur” books existed in 1993.

Morningstar recounts only one adventure, whereas Odysseus has many.

Odysseus has mostly specific antagonists (the cyclops Polyphemus, the witch-goddess Circe), but he also faces more amorphous “thems.” I think particularly of the anonymous mass of Lotus Eaters, Odysseus’s first memorable encounter (preceded only by sacking a city and then being driven off). Morningstar’s antagonists are an anonymous mass of humanities professors.

Odysseus is both opposed and aided by supra-human entities: gods. Poseidon and Zeus turn the winds against him; Hermes gives him a potion that allows him to resist witch-goddess Circe, who later gives him advice on how to get home. Living non-mythological creatures – other humans – aren’t too important, either as supporters or opponents.

Morningstar also attributes causal power to non-human entities. His real opponent is not people but rather the academic system that shapes them in what he analogizes to an evolutionary process. Like the Lotus Eaters, professors are ensorcelled, captured by powers greater than themselves.

Both Odysseus and Morningstar leave their story unfinished. The Odyssey switches back to a third person story for the ending battle in which Odysseus regains his home and wife. Morningstar ends with the call to continue the adventure:

“It is clear to me that the humanities are not going to emerge from the jungle on their own. I think that the task of outreach is left to those of us who retain some connection, however tenuous, to what we laughingly call reality. We have to go into the jungle after them and rescue what we can.”

This is more of a “The End… Or Is It?” ending. It doesn’t fit well with the Odyssey template. However, one of the uses of hero stories like the Odyssey was to rev up (motivate) followers, especially before a big battle. “The main function of poetry in heroic-age society appears to be to stir the spirit of the warriors to heroic actions by praising their exploits and those of their illustrious ancestors, by assuring a long and glorious recollection of their fame, and by supplying them with models of ideal heroic behaviour.” – brittanica.com (paywalled). Some kind of climax is needed in an adventure story – the big fight at the end of the superhero movie, confrontation with the final boss in a video game – and this fits well enough.

Structuralism and egregores

I’ve described Morningstar weaving elements of a hero’s journey into the essay. In a mild version of structuralism, it’s enough to say something like “If you deliberately subtitle your essay as an ‘adventure’, you describe a conflict with an ‘other’, you win the conflict, and you end by proposing your reader go with you on a similar adventure into a jungle (a dangerous place), it’s not surprising that you’ll reuse old heroic tropes, perhaps even unintentionally.” Another example of this might be the title: “How to Deconstruct Almost Anything.” I wondered a bit about the “almost,” since there’s nothing in the text that justifies it. Then I realized there are immense numbers of self-help-ish books with a title of that form: How to X Almost Anything. That template hovers out there in the culture, ready to flash to mind if you haven’t got anything better.

But I don’t think that gives a clear idea of how structuralists think. So let me take things in a more radical direction. Morningstar spends some time diagnosing why he and people like him don’t suffer from the failures of the professors. They have something on their side: “what we laughingly call reality,” specifically economic reality:

“[T]echnical people like me work in a commercial environment. Every day I have to explain what I do to people who are different from me – marketing people, technical writers, my boss, my investors, my customers – none of whom belong to my profession or share my technical background or knowledge. As a consequence, I’m constantly forced to describe what I know in terms that other people can at least begin to understand. My success in my job depends to a large degree on my success in so communicating. At the very least, in order to remain employed I have to convince somebody else that what I’m doing is worth having them pay for it.”

And:

“Engineering and the sciences have, to a greater degree, been spared this isolation and genetic drift because of crass commercial necessity. The constraints of the physical world and the actual needs and wants of the actual population have provided a grounding that is difficult to dodge.“ I note in passing that these two paragraphs are making different claims. The second alludes to facts about physical reality that really are “difficult to dodge.” The first is about persuasion: “I have to convince somebody else that what I’m doing is worth having them pay for it.” Persuading people – perhaps especially “my boss, my investors, [and] my customers” – is much less grounded in “what we laughingly call reality” than science is. There’s perhaps a bit of stolen valor here. It’s pretty common for non-scientists to enlist scientists when attacking the humanities and social sciences.

Commercial reality here is acting something like the gods that help and hinder Odysseus. Commercial reality has given Morningstar the equivalent of Hermes' potion that prevented him from being seduced by Circe. The market provides the discipline that academia lacks. Discipline is a theme running through both the Odyssey and the essay. Part of what makes Odysseus a hero is that he has greater discipline than his men, though even he needs imposed discipline (a potion, being tied to the mast) when dealing with the supra-human.

So what kind of thing is the market? It’s striking how easily it’s personified: type “Mr. Market” into a browser search bar and see how it autocompletes. A lot of people have adopted the term since Warren Buffett coined it. It comes naturally.

You can argue (and people have) that the market is usefully labeled an “egregore,” an autonomous entity of some sort that’s created by the unified activities, thoughts, and purposes of a group of people. An egregore acts independently of the people who created it, and its motives will generally not be identical to theirs.

A variant of the egregore more appealing to techies is the “Singularity.” Statistician Cosma Shalizi writes, in “The Singularity in Our Past Light-Cone,” that “The Singularity has happened; we call it ‘the industrial revolution’":

“Exponential yet basically unpredictable growth of technology, rendering long-term extrapolation impossible (even when attempted by geniuses)? Check.

“Massive, profoundly dis-orienting transformation in the life of humanity, extending to our ecology, mentality and social organization? Check.

[…]

“Creation of vast, inhuman distributed systems of information-processing, communication and control, “the coldest of all cold monsters”? Check; we call them “the self-regulating market system” and “modern bureaucracies” (public or private), and they treat men and women, even those whose minds and bodies instantiate them, like straw dogs.

“An implacable drive on the part of those networks to expand, to entrain more and more of the world within their own sphere? Check. (‘Drive’ is the best I can do; words like ‘agenda’ or ‘purpose’ are too anthropomorphic, and fail to acknowledge the radical novelty and strangeness of these assemblages, which are not even intelligent, as we experience intelligence, yet ceaselessly calculating.)”

Elsewhere, he writes:

“These things [which he doesn’t call egregores, but rather analogizes to H.P. Lovecraft’s shoggoths] emerge from the massed results of human social interaction and individual intelligence, and therefore are very different from human minds. In particular, they tend to have their own intrinsic dynamics, which are usually not things anyone intends, and often things no-one wants. […] That doesn’t mean they can’t be controlled; it means control is hard, and usually itself impersonal.”

So another parallel between the Odyssey and Morningstar’s essay is that they both feature, as quasi-characters, supra-human characters – Poseidon, Mr. Market, the system of academia, and so on – that constrain or aid mere humans.

Structuralism, I think, conceives of the patterns of communication known to a writer as a kind of egregore. Not entirely a tool you use to communicate your thoughts, but something that uses you – in a way akin to how Greek gods (Athena, Hera, and Aphrodite) used thousands of heroes for ten years to work out their differences.

Political correctness

“You need to hit all the beats of a story in general […] and your genre in perspective (I write romance, which has very specific ‘beats’ […].)” – “Ginger”

It’s widely recognized that genres (romance, superhero movies) have “beats” (Leví-Strauss might call them atoms) that must be included if a work is to be a good example of the genre. I claim that “the anti-political-correctness polemic” had, by 1993 become a genre of its own. I’ve separately documented the evolution of the rhetorical atoms/beats into a stable form, one that’s persisted to today. 1984 1987 1990 1991 (Today’s genre of “anti-woke” polemic hits the same beats, I think. Its main difference is that it’s expanded the list of opponents beyond the university.)

By describing himself as “Politically Incorrect” in opposition to professors who think “politics and cleverness are the basis for all judgments,” Morningstar was “activating” a particular template. He became obliged to hit various anti-PC beats, even if it made parts of his argument seem weird to people who don’t care about that instantiation of the culture war that has been enervating US culture since the bloody Sixties, not that I have an opinion.

And I think Morningstar’s essay does hit many of the beats. For example:

-

Anti-PC rhetoric requires a clear “us” vs. “them.” The “them” must be actively antagonistic to “us.” This accounts for the strange last words of the essay: “don’t let them intimidate you” and the earlier “nothing to be afraid of.” Morningstar never shows the professors trying to intimidate anyone – the belief that they are the intimidating, hostile sort is just an assumption of the genre. If anyone is presented as intimidating, it’s Morningstar and his techies. The Wired account has it that “the tech heads in the audience refused to be intimidated by quotes from Frenchmen, and heckled the po-mo’s off the stage.” Morningstar counters “we did not shout down the postmodernists. We made fun of them.” Perceptions no doubt differed; eyewitness testimony is unreliable, even from uninvolved observers. Even if Wired is wrong in its claim of a hecker’s veto, it’s not fun having someone supported by an audience making fun of you to your face. Whether it’s “intimidating”… well, it depends on the person and the context. (Morningstar’s Wired link is dead; thanks to Jan Dietrich for finding a working one.)

-

A theory must be proposed for why the professors say the crazy things they say. Morningstar’s evolutionary metaphor is unique to him, as far as I know, but what matters is that an explanation must be included. It must be clear that they didn’t arrive at their beliefs via honest investigation or reasoning but because they value the wrong things (“politics and cleverness”). That Morningstar devoted 27% of the essay to this topic, rather than the stated one, supports classifying it as an anti-PC polemic.

-

The professors must be political actors, motivated by political beliefs. Specifically, left-wing dissatisfaction with the status quo. That’s why Morningstar must claim professors judge based on “politics and cleverness,” without presenting any evidence for the “politics” part. Evidence isn’t needed: everyone knows professors are aggressively left-wing. It’s why Marx appears almost as often in Morningstar’s essay as in Culler’s book. Some variant of “marx” appears only four times in Culler’s index. Twice it’s referring to other types of literary analysis than deconstruction. Once it’s a brief discussion of two books deconstructing texts of Marx’s. Once it’s the statement “he [Derrida] is critical of Marxism.” At the time of Morningstar’s writing, Marxists and deconstructionists were on the outs. Prominent Marxist critic Terry Eagleton referred to it as “do[ing] little more than reproduc[ing] some of the most commonplace topics of bourgeois liberalism” (p. 483) and “in a world groaning in agony, where the very future of humankind hangs by a hair, there is something objectionably luxurious about it” (p. 486). Eagleton, like Morningstar, dislikes deconstruction because it’s detached from the real world, though they have no doubt very different ideas of the nature of that world. (Marxists and Derrida later made up, but that was after Morningstar’s essay.) Marx is being used as the boogeyman.

-

A common structure is the To Be Sure Sandwich. Some aspect of “political correctness” is attacked, which segues into some soft acknowledgement of some kind of merit to the opposition’s position (“To be sure, racial discrimination remains a problem”), and then reverts to the attack. An important characteristic is that the “to be sure” has little or no effect on what follows: the author’s conclusions or recommendations. I don’t know that Morningstar’s essay is the best example of the Sandwich, but its “Buried in the muck, however, are a set of important and interesting ideas” paragraph seems to fit, as it’s immediately followed by a reiteration of his epistemic closure argument.

I’ll shift out of the numbered list for my closing claim. I’ll return to the paradox of appeals to authority, because I think Morningstar’s question of “who is making the judgment” is central. I’m not in general a big fan of the kind of analysis that leans heavily on one single little slip by the author, but I think it works here.

Audiences and aims

Let’s look at how Morningstar characterizes himself in the essay.

“I’d never before had the experience of being quite this baffled by things other people were saying. I’ve attended lectures on quantum physics, group theory, cardiology, and contract law, all fields about which I know nothing and all of which have their own specialized jargon and notational conventions. None of those lectures were as opaque as anything these academics said.”

My wife is an (emeritus) professor of veterinary medicine. She has a giant binder with papers she’s authored or coauthored. One from near the front is “Hematologic Responses in Llamas with Experimentally-Induced Iron Deficiency Anemia,” published in Veterinary Clinical Pathology, Vol. 22, No. 3 (1993). It begins:

“Hematologic abnormalities consistent with iron deficiency anemia were experimentally induced in two healthy llamas by repeated phlebotomy. Hematologic abnormalities included erythrocyte microcytosis and hypochromia, decreased hemoglobin concentration, hypoferremia, and decreased transferrin saturation.”

Now there’s some jargon!

I asked her, “If you were presenting this at a conference, would you define any of the words in that sentence?” She answered:

“It depends on the conference. At [an academic conference for internal medicine people] I wouldn’t, but at a conference with general practitioners I’d define some of the terms. All vets would have learned the terms, but some are not used commonly so I’d review those.”

Professors like Dawn present to three different groups: peer experts (other professors of internal medicine), general practitioners fulfilling some of their continuing education requirements, and laypeople (like, for example, a club for llama owners during the big fad for llamas in the 1990s). When Morningstar writes that “Every day I have to explain what I do to people who are different from me – marketing people, technical writers, my boss, my investors, my customers – none of whom belong to my profession or share my technical background or knowledge,” he is performing the third sort of explanation: expert to layperson. (Explaining his work to another programmer with a different background would be akin to expert to practitioner.)

I have to suspect that Morningstar was on the receiving end of expert-to-layperson explanations when he heard those talks “on quantum physics, group theory, cardiology, and contract law.”

The tragicomedy of the Second International Conference on Cyberspace, I suspect, is that the professors came expecting expert-to-expert and encountered half an audience with the same expectation and half expecting expert-to-layperson. Another report on the conference includes the conference announcement (call for papers?). It says “the focus of the Conference is theoretical and conceptual” and “not primarily about the enabling technology” right up front. Reading the whole thing, I can’t say the professors weren’t justified in thinking there’d only be their humanities and social science peers there, with a scattering of techies “with a foot in the lit crit camp but also [people] of clear intellectual integrity who [were] not fool[s].”

In a plausible alternate timeline, the conference could have been rescued had the two sides talked to each other about their expectations and puzzlements. Long-term relationships could have been started, cemented by a shared ruefulness at how close the conference had come to turning out like… it did in our timeline.

And perhaps structuralism helps explain. The same structure that can help shape an essay can help shape behavior at a conference. The US political environment in 1993 was so saturated with talk of “political correctness” that – I think it’s not outlandish to hypothesize – it helped shape the techies' reactions. Their minds already had a structure where professors are the other, the enemy, and they’re against normal, sensible people like you.

In a way, you can sort of think of Morningstar’s essay as undermining itself – just like deconstructionists think texts are supposed to do! – through its own patent exaggerations and uncharitable, over-broad, and unsourced assertions. Structuralism of the Leví-Strauss sort emphasizes relationships (between brother and sister, for example). The anti-PC zeitgeist of 1993 delivered to susceptible people a prepackaged set of relationships, most particularly between “university people” and “people in the real world” (characterized by science, engineering, and commerce in the essay) and between “fancy talk” and “plain truth.” This pre-determined content wouldn’t allow the essay to do what it purports to do: explain and assess a particular style of analysis. The essay goes all over the place and the explanation isn’t very good.

To be blunt: the meaning of the essay – the main take-away – is:

“We are programmers. We, led by Chip Morningstar, are smarter, wittier, and more virtuous than those humanities and social science professors over there. They are unscrupulous people with bad motives, embracing a bad system.”

The anti-PC movement is an essentially conservative one, in the sense that conservatism believes society is hierarchical and that’s the way it should be. (Both descriptive and prescriptive.) There are people who rule due to their inherent characteristics (birth, IQ, wealth, some other measure of merit) and people who are meant to be ruled. Those who are served, and those who serve. People who are entitled to authority and those who submit to judgment.

The rage of the anti-PC polemic is that those who are meant to serve (for example, by transmitting Western culture to the next generation) are doing their own thing and are thereby threatening us. They act and talk so as to evade our judgment and authority. In this essay, the professors' job was to explain to techies, and they did something else. It is necessary to assert status by demonstrating (claiming) that their “something else” is trivial.

Click for XKCD Explained.