Structuralism was an intellectual movement most active a couple of decades after World War II, but I think it’s something people with a certain intellectual temperament gravitate to. I certainly did when I was younger, though I no longer do.

I need a short summary of it that I can refer to. I could just drop a link to Wikipedia or the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, but I want to highlight certain features that are important to how I think of it.

Structuralism in its modern form is commonly traced back to linguistics. From there, it came to influence the humanities, the social sciences, and mathematics. “The [Bourbaki] group is noted among mathematicians for its rigorous presentation and for introducing the notion of a mathematical structure, an idea related to the broader, interdisciplinary concept of structuralism.” – Wikipedia article on the French mathematicians that published under the name of Nicolas Bourbaki.

I’ll start with two frequently-used examples, one from literary analysis and one from anthropology, then add one from mathematics.

Analysis of fairy tales (humanities)

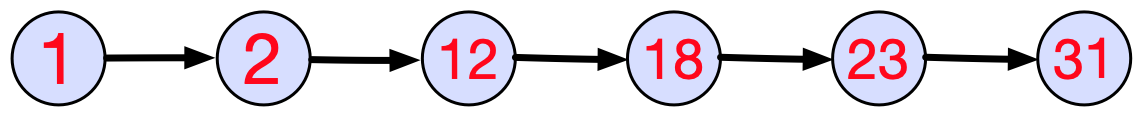

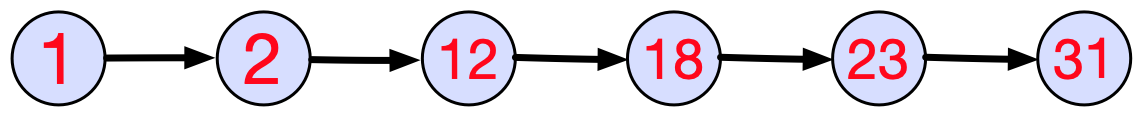

In the late 1920s, Vladimir Propp analysed 100 Russian folk tales to see what they had in common. He said that they were composed of combinations of 31 plot points. Here are some examples: Taken from “Propp’s Morphology of the Folk Tale”

- 1. Absentation: Someone goes missing

- 2. Interdiction: Hero is warned

- …

- 12. Testing: Hero is challenged to prove heroic qualities

- …

- 18. Victory: Villain is defeated

- …

- 23. Arrival: Hero arrives unrecognized

- …

- 31. Wedding: Hero marries and ascends the throne

You’ve likely read some folk tales that include those plot points. However, there are particular rules that must be followed:

- In any given tale, between zero and 30 plot points may omitted – though a tale using all 31 would be wildly overstuffed, and a tale consisting of only, say, “Hero arrives unrecognized” wouldn’t be much of a story.

- In a story, plot point m must occur before any plot point later in the list of 31. That is, once the hero arrives unrecognized (23), there’s no backtracking to testing the hero (12) or defeating the villain (18).

Propp doesn’t claim the people who create or retell folk tales consciously know the plot elements and the rules, only that they ended up using them. There’s also (as far as I know), no explanation of why those particular plot points or rules. His theory is purely descriptive.

Kinship structures (social science)

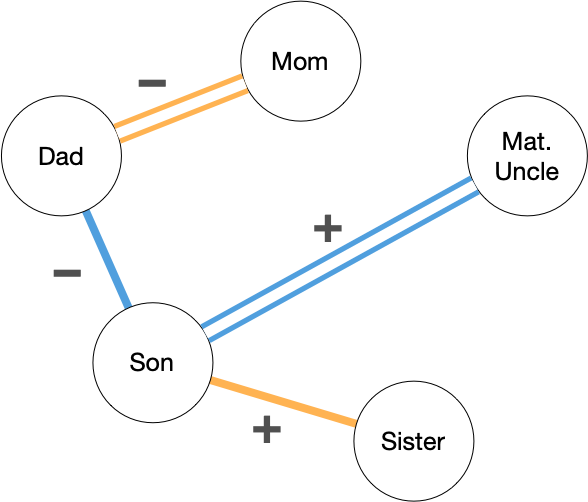

Claude Lévi-Strauss was French anthropologist who applied structuralist ideas to anthropology. In chapter 4 of his 1958 book Structural Anthropology he described a structure underlying kinship systems in societies where marriage is implemented by one man giving a sister or daughter to another. He did this by looking at examples and trying to spot some sort of regularity.

One he found involved five people: a husband and wife, their son and daughter, and the wife’s brother (the son’s maternal uncle).

These people have relationships to each other, which he simplified as either “warm” or “cold.” For example, in some cultures, brothers and sisters aren’t allowed to be under the same roof at the same time. That’s a cold relationship. In others, brothers and sisters are so close they sleep in the same bed. Warm.

There are four relationships that matter: between husband and wife, father and son, brother and sister, and finally son and maternal uncle. Given the warm/cold dichotomy, that makes 16 possible combinations of warmth or coldness between the relevant people. But (Lévi-Strauss claims) such human cultures use only four, because of two rules:

-

The relationship of son to father must be the opposite of that between son and maternal uncle. If the society is one where the father gives orders to the son and expects unquestioning obedience, it will be the maternal uncle who’ll spoil the son with gifts and sooth his hurt feelings. Or if the father is indulgent, the uncle must be a stern law-giver.

-

The relationship between husband and wife must be the opposite of that between brother and sister. If husband and wife have a warm, friendly relationship, the son and daughter won’t. If the son and daughter sleep in the same bed, the culture might be one where the wife and husband only meet when the husband sneaks into her separate dwelling place for sex.

That given, a particular culture can be described by a picture like this:

Structuralist theories often lend themselves to good old node-and-edge diagrams, like the two above. The nodes name entities. Edges correspond to relationships.

I said “nodes name entities deliberately. Typically, a structuralist theory gives you little to no information about a node other than an arbitrary label. The oomph comes from the relationships. I’ll say more in a minute.

Groups (mathematics)

The mathematical concept of a group is structuralist. There are four entities: a set of things (integers, say, labeled G), two operations (+ and parentheses/grouping) and an identity (0). There are three formulae that mention those entities:

- For all

a, b, cinG,(a+b)+c = a+(b+c)(associativity) 0+a = a+0 = a(what the identity entity means)- Given an

a, there exists absuch thata+b=0andb+a=0(negation)

Alternately, you could say there are three relationships that tie the entities together.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen a node-and-edge diagram for groups, but I offer this:

I suppose this does highlight that + is the… most important? most central? of the entities, as it participates in all the relationships.

Notice that actual numbers – the things being operated on – don’t appear in the diagram. That’s because groups apply to more than just numbers. For example, the three rules apply to the Rubik’s Cube group. What are numbers in arithmetic are rotations of one of the cube’s faces by some multiple of 90 degrees, the + operator means “then” as in “do rotation x, then do rotation y,” and the identity element is “rotate zero degrees.”

Assumptions of structuralism

Lévi-Strauss credited linguist Nikolai Trubetzkoy (1890–1938) with writing down four assumptions of structuralism. I harp on the second and fourth.

-

Conscious behavior (such as producing sentences) is supported by (or driven by) unconscious structures. So, more important than studying a language’s grammar is studying the underlying structures that control which grammatical rules you absolutely will find in a language, which rules might be found, and which definitely won’t be found.

-

What matters is relationships between entities, not properties of the entities themselves. The father’s character doesn’t matter in Lévi-Strauss’s theory of kinship; what matters is his relationship to his wife and to his son.

It’s actually better to think of relationships between relationships. So Lévi-Strauss is saying that the relationship between the mom-dad relationship and the sister-brother relationship is that they must be opposite.

-

The purpose of the work is to tease out the underlying structure. That’s a little circular: “structuralism is about structure.” So I’ll say what it means is that you should describe all the relevant relationships between entities and how the relationships relate to each other.

-

A structuralist theory must explain multiple real-world examples. Trobriand culture is matrilineal, and Tonga culture is patrilineal; Lévi-Strauss’s kinship rules work for both.

Applying structuralist theories

It’s possible to treat a model or a theory as an aesthetic object for contemplation, akin to the sun setting into the ocean or a dramatic thunderstorm in the mountains. But they’re usually used for solving problems.

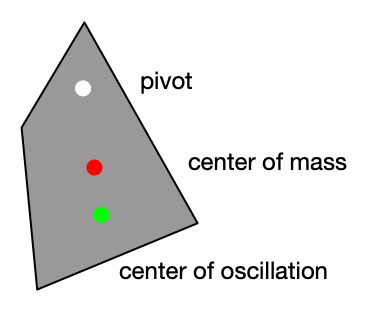

The problems can be of various types. A theory can be used to generate new theories. Consider the simple pendulum:

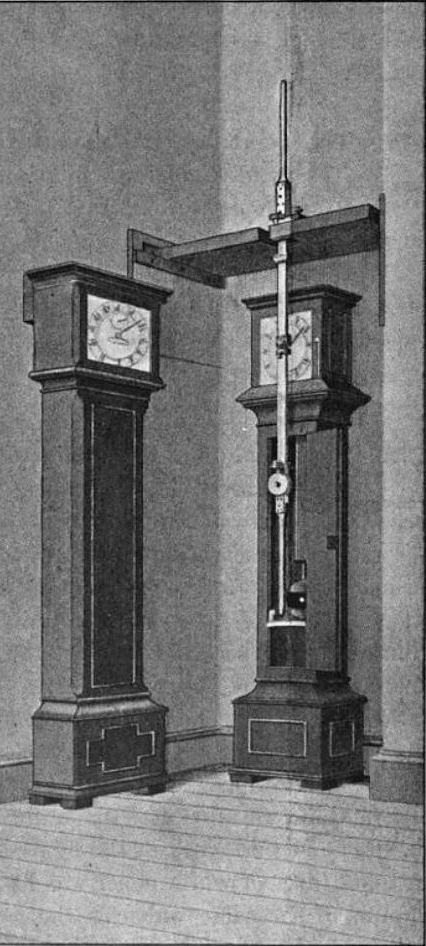

Galileo discovered that the amount of time it takes for a pendulum to swing is independent of how far it swings (the amplitude), which makes it useful for keeping time. But that isochronism only works for small amplitudes. Some years later, aided by mathematics Galileo didn’t have (calculus), Huygens extended the theory of the pendulum to account for larger amplitudes. He also extended the theory from bob-type pendulums like the one above to “physical pendulums” where you can’t pretend all the mass is contained in a single point:

Along the way, he showed that you can flip such a pendulum, suspending it from the center of oscillation (below the center of mass, as shown above). The flipped version will have the same period, and the old pivot point will be the new center of oscillation, which is neat.

But theories are also applied to solve particular non-theoretical problems. The period of a pendulum depends on the acceleration of gravity (g). But that acceleration varies depending where on the earth you are (because the earth isn’t perfectly round and its surface is bumpy). So you can work backwards from a measured period to calculate the value of local gravitation (which is apparently useful to know for things like precise navigation and mapping).

Kater's pendulum (right)

Kater's pendulum (right)

I’m most interested in this sort of problem-solving, but pitfalls in structuralist theories can get in the way.

The details men don’t see

(That’s a labored reference to “The Women Men Don’t See” by Alice Sheldon, writing as James Tiptree Jr.)

I don’t know for sure, but I presume Propp was analyzing long-lasting folk tales (the Russian equivalents of the Brothers Grimm tales). Suppose I want to write my own tales that will last a couple of hundred years. What use would I make of Propp’s rules for folk tales? Because Propp’s theory isn’t causal (doesn’t explain underling mechanism), there are several possibilities:

-

Propp’s structuralist theory is a chance regularity in what was, after all, only 100 stories. If so, it has nothing to do with longevity. (Call this case no-causality.)

-

Longevity and the structure are both caused by some underlying phenomenon. Just because the phenomenon causes Propp’s rules to apply doesn’t mean that following the rules will cause the phenomenon – in which case, my rule-abiding tales wouldn’t be “sticky.” (side-effect)

-

Propp’s rules have some causal role in longevity, but it’s minor. He may have discovered the equivalent of the formula that describes the effect of large amplitudes on the period of a pendulum’s swing. That does allow you to fine-tune calculations of period, but such fine tuning is meaningless unless you’re already making use of the base property of isochronicity. That is, the problem’s really solved by something else. (minor-causality)

-

Propp has indeed identified a structure that is, by itself, a sufficient cause of longevity. (sufficient-causality)

I’d be willing to bet against no-causality and side-effect, but you’d have to give me pretty good odds to bet on sufficient-causality. Call me a pessimist, but my preferred bet would be that the truth is somewhere between minor-causality and sufficient-causality: that Propp’s rules aren’t enough by themselves to achieve my longevity goal. So it would be well worth my time to investigate other possibly causes of longevity before I put a lot of effort into writing.

My bias for over 40 years has been to focus such investigation on what a proposed explanation leaves out. Anything that draws your attention to certain aspects of a problem invariably draws your attention away from other aspects. Because structuralism is monomaniacal about relationships, that suggests two questions:

What’s important about the entities?

Not much information is given about the folk tale plot points. Consider “14. Acquisition: Hero gains magical item.” The text at the link reads:

The hero now acquires an item of some kind, often magical and usually being given by the donor as reward for passing the test. This may be potion, a weapon, and so on. The reward may also be more mundane, such as help from others or critical knowledge, but nevertheless is essential in helping the hero in completing the quest.

I have lots of questions.

-

What’s the difference between the tales that use a magical item and those that use a mundane one?

-

How often is it that the use of the item is straightforward, vs. how often there’s some sort of surprising twist? (I might be tempted to have the hero use the magical sword, crowbar-like, to pry up a manhole cover instead of using it in the expected way, but is that a modernist sort of irony that the target audience would think dumb?)

-

The hero and villain probably fit various stereotypes. What are they? (For example, in central Europe, a lot of stories involve a peasant who cleverly outwits someone with power. In “The Clever Peasant,” a Ukrainian folk tale, It’s a stretch to call Ukraine “central Europe,” but it seems most Ukrainians justifiably want to be as far in the direction away from Russia as possible. the titular peasant outsmarts a standoffish ruler. Notably, in this story, the peasant humiliates the ruler but hasn’t really changed the situation. The ruler still rules; the peasant is still subject to him. Sadly, that’s what’s so far happened with Putin, despite how the brave Ukrainians keep outsmarting him. In “The Peasant and the Devil,” a deal with the devil nets the clever peasant a nice treasure.)

-

And so on.

None of these are really about relationships, but the answers could be important for readers, if not for structuralist theory-makers.

What relationships are missing?

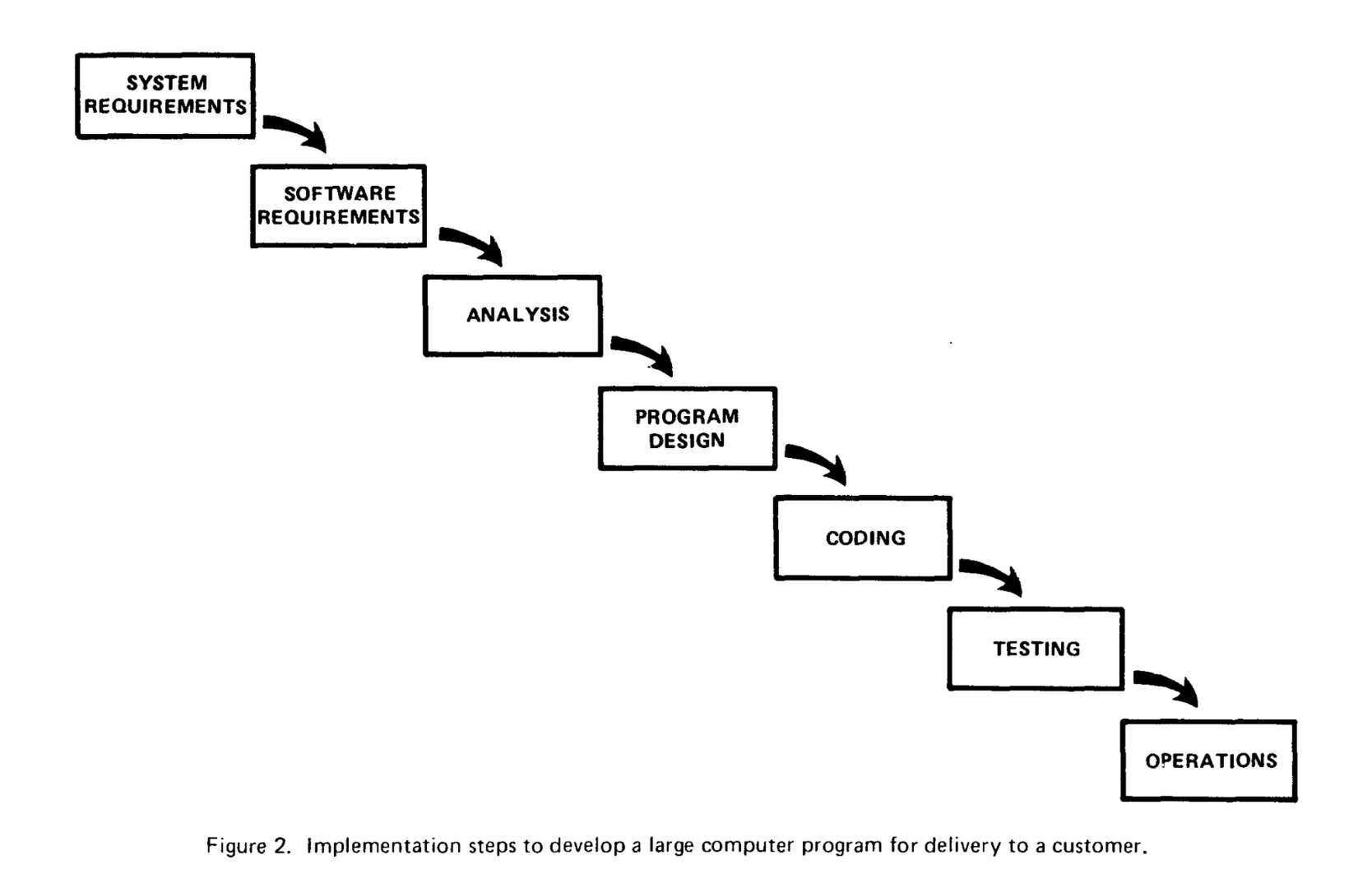

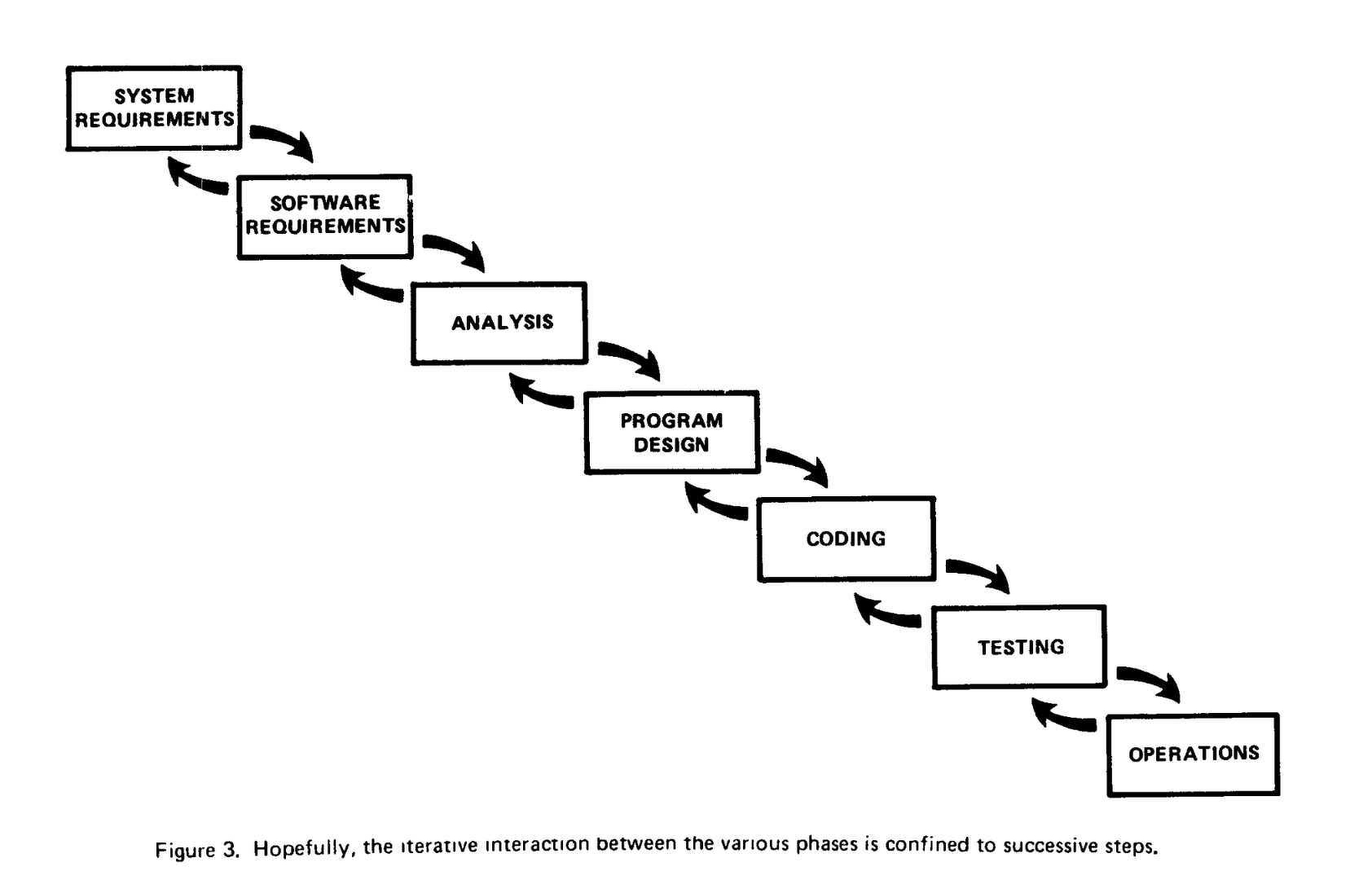

Whenever I see a diagram with all the arrows going in the same direction, I get suspicious, especially when the arrows represent time or importance. For a software development example, see “Oops! The Winston W. Royce Story. It’s a podcast episode, but there’s a transcript. Since there are no pictures, you might prefer a wikified version with diagrams. Here are two of the pictures (from Royce’s original). (You can click to enlarge in a new tab.) Propp’s structure of folk tales is linear in that way.

What other types of arrows might there be? One that comes to mind links nodes with common settings or characters. What I want to focus on are back references.

-

Item: The Russian playwright Anton Checkhov is remembered for advice that’s come to be called “Checkhov’s Gun,” commonly quoted as “If in the first act you have hung a pistol on the wall, then in the following one it should be fired.”

-

Item: The callback is a common technique in standup comedy. You tell some jokes about a topic. You move on to other topics. Toward the end of your set, you make a new joke that refers to the original topic. People laugh harder when they notice the reference. The brick joke is a classic example, though weak because the first part isn’t actually funny.

For some reason, people like it when they are surprised by an unexpected reference to something set up earlier, especially when they didn’t predict that the setup was going to be used.

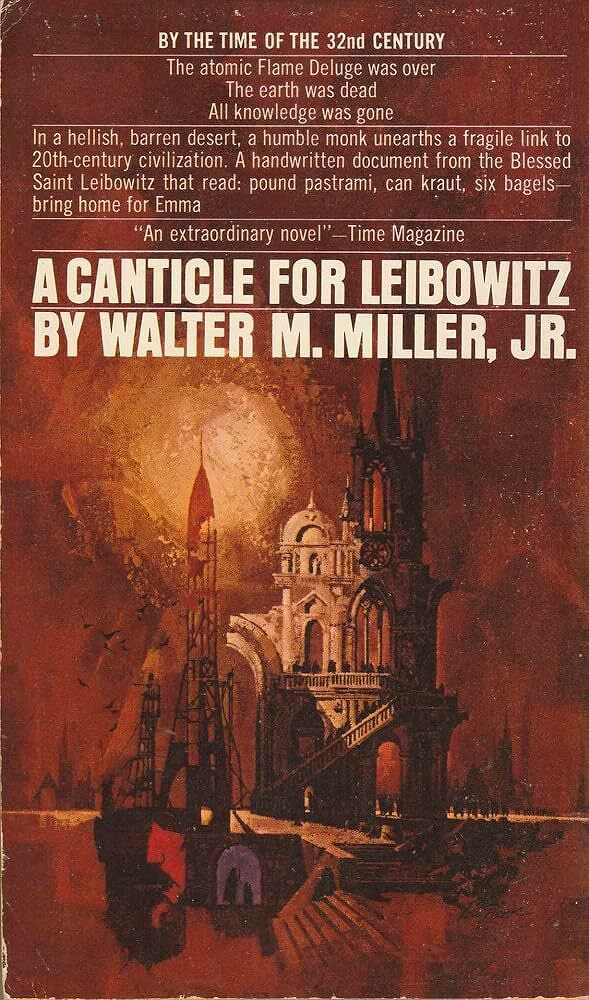

An obscure post-apocalyptic reference

An obscure post-apocalyptic reference

Which might lead me to think about comparing folk tales to epics like The Iliad. Both are from oral cultures, and presumably are tailored to be memorable. How does that work? I would want to use their tricks with my folk tales, for memorability in a post-literary world.

As I’m not actually going to write folk tales, I’ll stop describing how I’d prepare.

On diagrams

Structuralist theories (like Lévi-Strauss’s) lend themselves well to visualization with the good old-fashioned node-and-edge diagrams, as you’ve seen above.

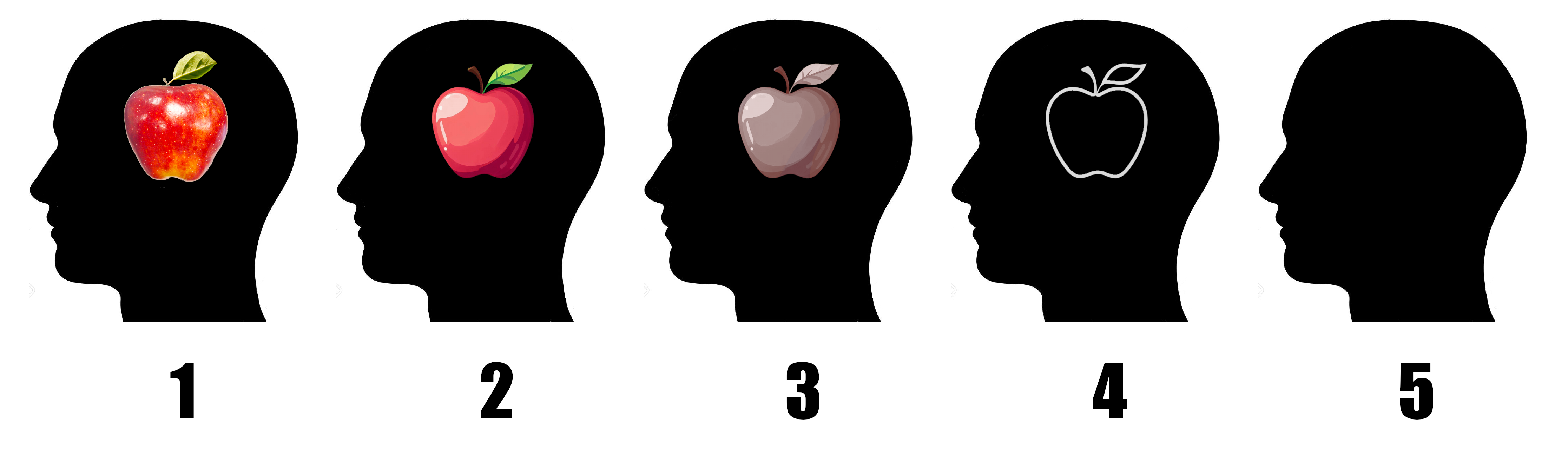

Maybe it’s sour grapes, since I am practically aphantasic, being between 4 and 5 on the aphantasia scale:

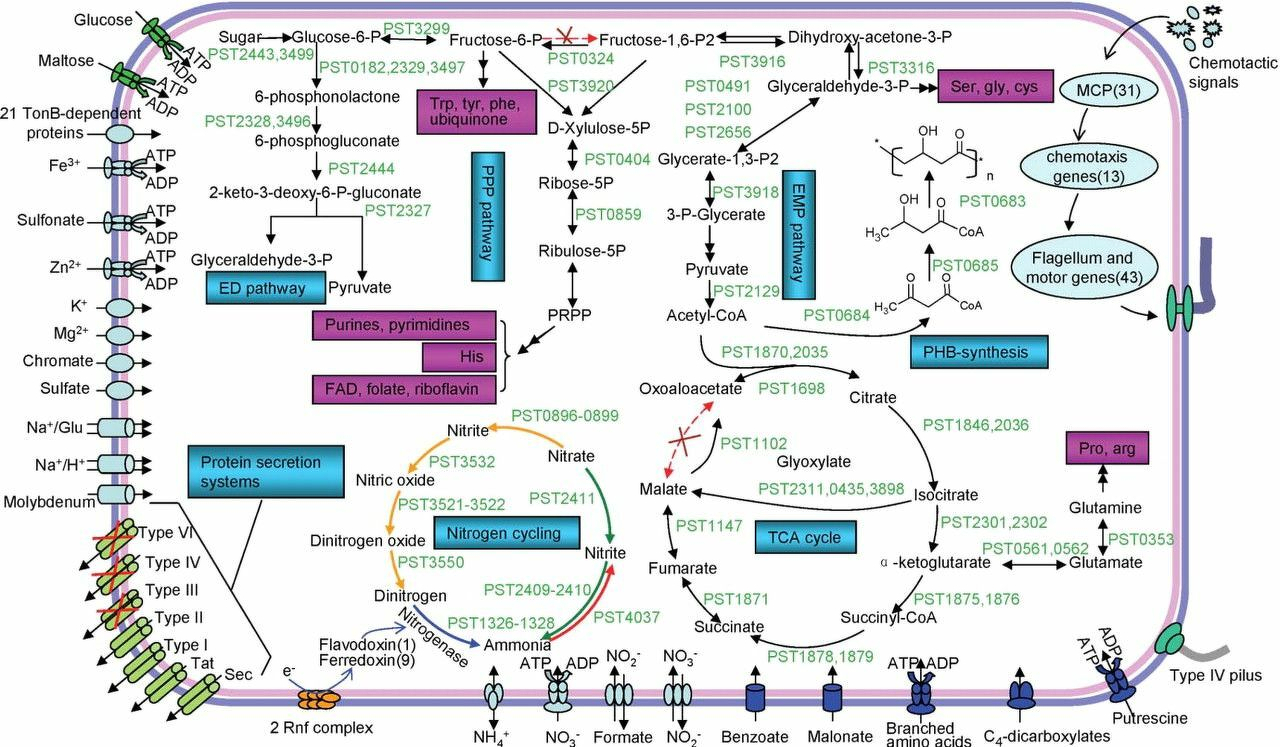

Your metabolism is kludgy. Note that the drawing has imposed aesthetically-pleasing shapes on the underlying mess. That's telling, I think.

Your metabolism is kludgy. Note that the drawing has imposed aesthetically-pleasing shapes on the underlying mess. That's telling, I think.

This is just one of those biases you should beware of. In fundamental physics and mathematics, influential people have believed that “Beauty is truth, truth beauty — that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.“ Keats, “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” 1819. Maybe so, but are you doing pure – rather than applied – physics or mathematics? How much do you want to bet that your aesthetics apply to the problem at hand?

I think, playing the odds, you’ll be better off being suspicious when beauty is implied to be a criterion for acceptability or tolerability or truth.

The big takeaway

It’s good to know about structuralism. It’s better to know that structuralism is but one kind of theory/model/abstraction, one that often cannot stand alone. It’s best to know that all abstractions divide the world into two categories – the essentials and the ignorable details – and, in a particular situation, they’re likely to get the dividing line wrong.

Bad

Bad

Better

Better