binary

Structuralism

Structuralism was an intellectual movement most active a couple of decades after World War II, but I think it’s something people with a certain intellectual attitude gravitate to. I certainly did when I was younger, though I no longer do.

I need a short summary of it that I can refer to. I could just drop a link to Wikipedia or the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, but I want to highlight certain features that are important to how I think of it.

Structuralism in its modern form is commonly traced back to linguistics. From there, it came to influence the humanities, the social sciences, and mathematics. “The [Bourbaki] group is noted among mathematicians for its rigorous presentation and for introducing the notion of a mathematical structure, an idea related to the broader, interdisciplinary concept of [[Structuralism]].” – Wikipedia article on the French mathematicians that published under the name of Nicolas Bourbaki. I highlight this to head off a reaction that structuralism is just something for woolly-headed humanists.

I’ll start with two frequently-used examples, one from literary analysis and one from anthropology.

Analysis of fairy tales

Vladimir Propp outlines a story foo

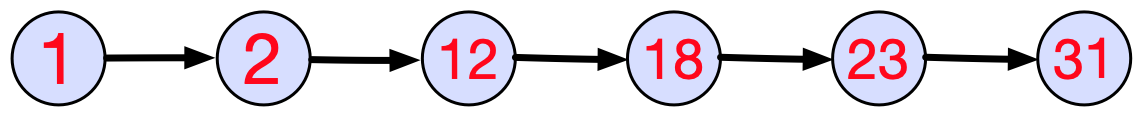

In the late 1920s, Vladimir Propp analysed 100 Russian folk tales to see what they had in common. He said that they were composed of combinations of 31 plot points. Here are two examples: Take from “Propp’s Morphology of the Folk Tale”

- 1. Absentation: Someone goes missing

- 2. Interdiction: Hero is warned

- …

- 12. Testing: Hero is challenged to prove heroic qualities

- …

- 18. Victory: Villain is defeated

- …

- 23. Arrival: Hero arrives unrecognized

- …

- 31. Wedding: Hero marries and ascends the throne

You’ve likely read some fairy tales that include those plot points. However, there are particular rules that must be followed:

- In any given fairy tale, between zero and 30 plot points may omitted – though a tale using all 31 would be wildly overstuffed, and a tale consisting of only, say, “Hero arrives unrecognized” wouldn’t be much of a story.

- In a story, event m must occur before any event later in the list of 31. That is, once the hero arrives unrecognized (23), there’s no backtracking to testing the hero (12) or defeating the villain (31).

Propp doesn’t claim the people who create or retell fairy tales consciously know the plot elements and the rules, only that they end up using them. There’s also (as far as I know), no explanation of why those particular plot points or rules. His theory is purely descriptive.

Kinship structures

[Claude Lévi-Strauss] was French anthropologist who applied structuralist ideas to anthropology. In chapter 4 of his 1958 book Structural Anthropology he described a structure underlying kinship systems in societies where marriage is organized around one man giving a sister or daughter to another. He did this by looking at examples and trying to spot some sort of regularity.

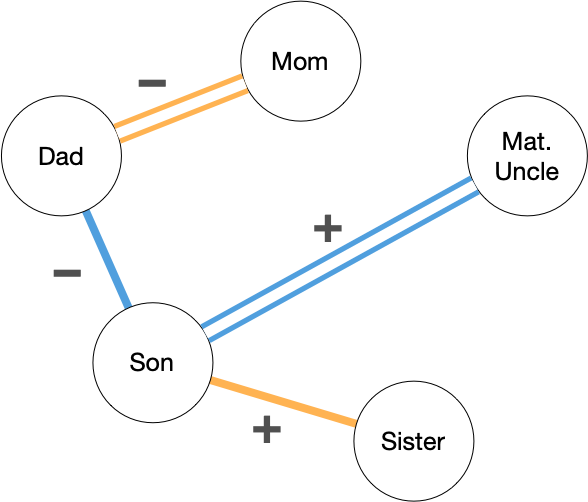

One he found involved five people: a husband and wife, their son and daughter, and the wife’s brother (the son’s maternal uncle).

These people have relationships to each other, which he simplified as either “warm” or “cold.” For example, in some cultures, brothers and sisters aren’t allowed to be under the same roof at the same time. That’s cold. In others, brothers and sisters are so close they sleep in the same bed. Warm.

There are four relationships that matter: between husband and wife, father and son, brother and sister, and finally son and maternal uncle. Given the warm/cold dichotomy, that makes 16 possible combinations of warmth or coldness between the relevant people. But (Lévi-Strauss claims) such human cultures use only four, because of two rules:

-

The relationship of son to father must be the opposite of that between son and maternal uncle. If the society is one where the father gives orders to the son and expects unquestioning obedience, it will be the maternal uncle who’ll spoil the son with gifts and sooth his hurt feelings. Or if the father is indulgent, the uncle must be a stern law-giver.

-

The relationship between husband and wife must be the opposite of that between brother and sister. If husband and wife have a warm, friendly relationship, the son and daughter won’t. If the son and daughter sleep in the same bed, the culture might be one where the wife and husband only meet when the husband sneaks into her separate dwelling place for sex.

That given, a particular culture can be described by a picture like this:

Assumptions of structuralism

Lévi-Strauss credited linguist Nikolai Trubetzkoy (1890–1938) with writing down four assumptions of structuralism. The second is the one I tend to harp on.

-

Conscious behavior (such as producing sentences) is supported by (or driven by) unconscious structures. So, more important than actually studying a language’s grammar is studying the underlying structures that control which grammatical rules you absolutely will find in a language, which rules might be found, and which definitely won’t be found.

-

What matters is relationships between entities, not properties of the entities themselves. The father’s character doesn’t matter in Lévi-Strauss’s theory of kinship; what matters is his relationship to his wife and his son.

It’s actually better to describe it as relationships between relationships. So Lévi-Strauss’s is saying that the relationship between the mom-dad relationship and the sister-brother relationship is that they must be opposite.

-

The purpose of the work is tease out the underlying structure. That’s a little circular: “structuralism is about structure.” So I’ll say what it means is that you should describe all the relevant relationships between entities and how the relationships relate to each other.

-

A structuralist theory must explain multiple real-world examples. Trobriand culture is matrilineal, and Tonga culture is patrilineal; Lévi-Strauss’s kinship rules work for both.

Pity the poor entity

Structuralism lends itself to the venerable node-and-edge graph. I gave two examples above. The nodes are entities and the edges are relationships. Everything worth knowing about the entities – at least from the perspective of the particular theory – is captured in the relationships.

By analogy consider the mathematical concept of a group in mathematics. There are three entities: a set of things (integers, say, labeled G), one operation (+) and an identity (0). There are three formulae that mention those entities:

- For all

a, b, cinG,(a+b)+c = a+(b+c)(associativity) 0+a = a + 0 = a(what identity means)- Given an

a, there exists absuch that a+b=0andb+a=0`.

Those relate the entities. They all describe everything you can know about them. These defining relationships don’t just apply to integers: functions about rotating or flipping cubes form a group that follows the same laws. But this is only possible if you commit to not caring about the differences between applying functions and adding numbers.

This is as it must be for structural theories because (per Trubetzkoy) they are required to be universal. That’s achieved by treating entities as irrelevant.

However, quite a lot of the time they’re not. So I think it’s wise to push back when evaluating the work of a structuralist-type person. Ask: In this particular situation, do the properties of the entity overwhelm the generalization?

Pretty pictures

Another way that a structuralist theory can go astray is by oversimplifying relationships or by omitting useful ones.

Oversimplifying Recall that Lévi-Strauss simplified relationships between people to a binary value: “warm” or “cold.” If you’re a Faithful Reader, you know that complexity reduced to a binary makes me suspicious. Lévi-Strauss quite properly presents his results as preliminary, and the binary as a simplification, but I’m curious what later research was done. (Though not enough to dig into the literature.)

Structuralist descriptions of reality can usually use the trusty node-and-edge diagram (as I did twice above).

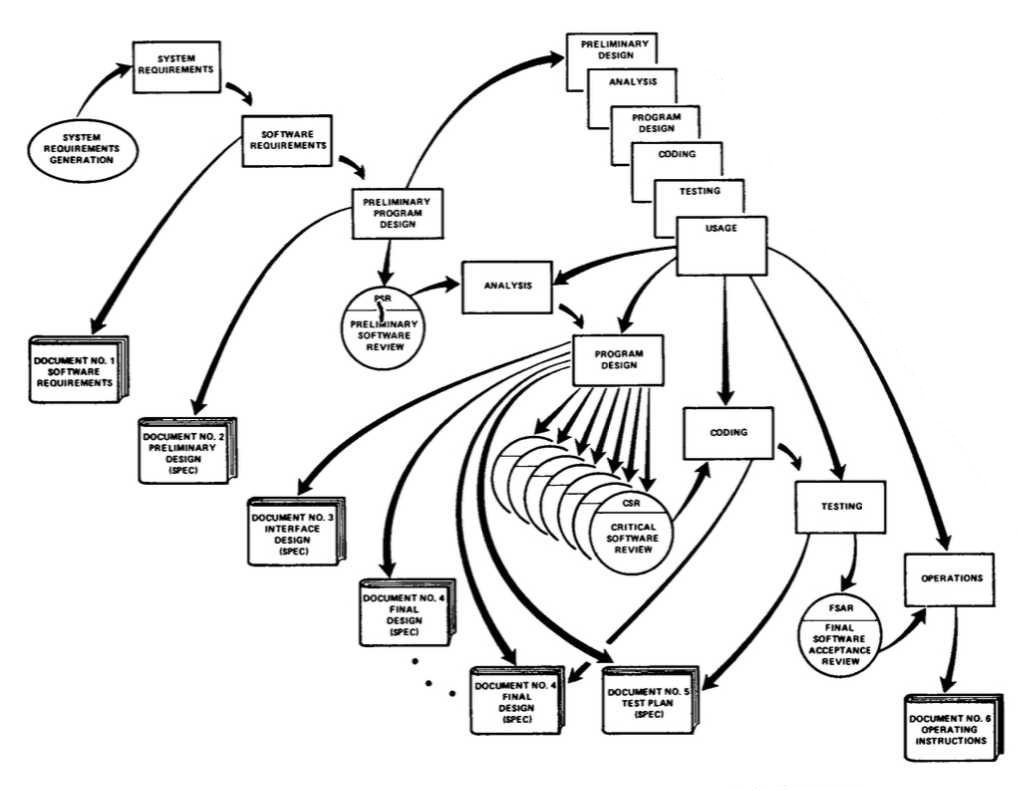

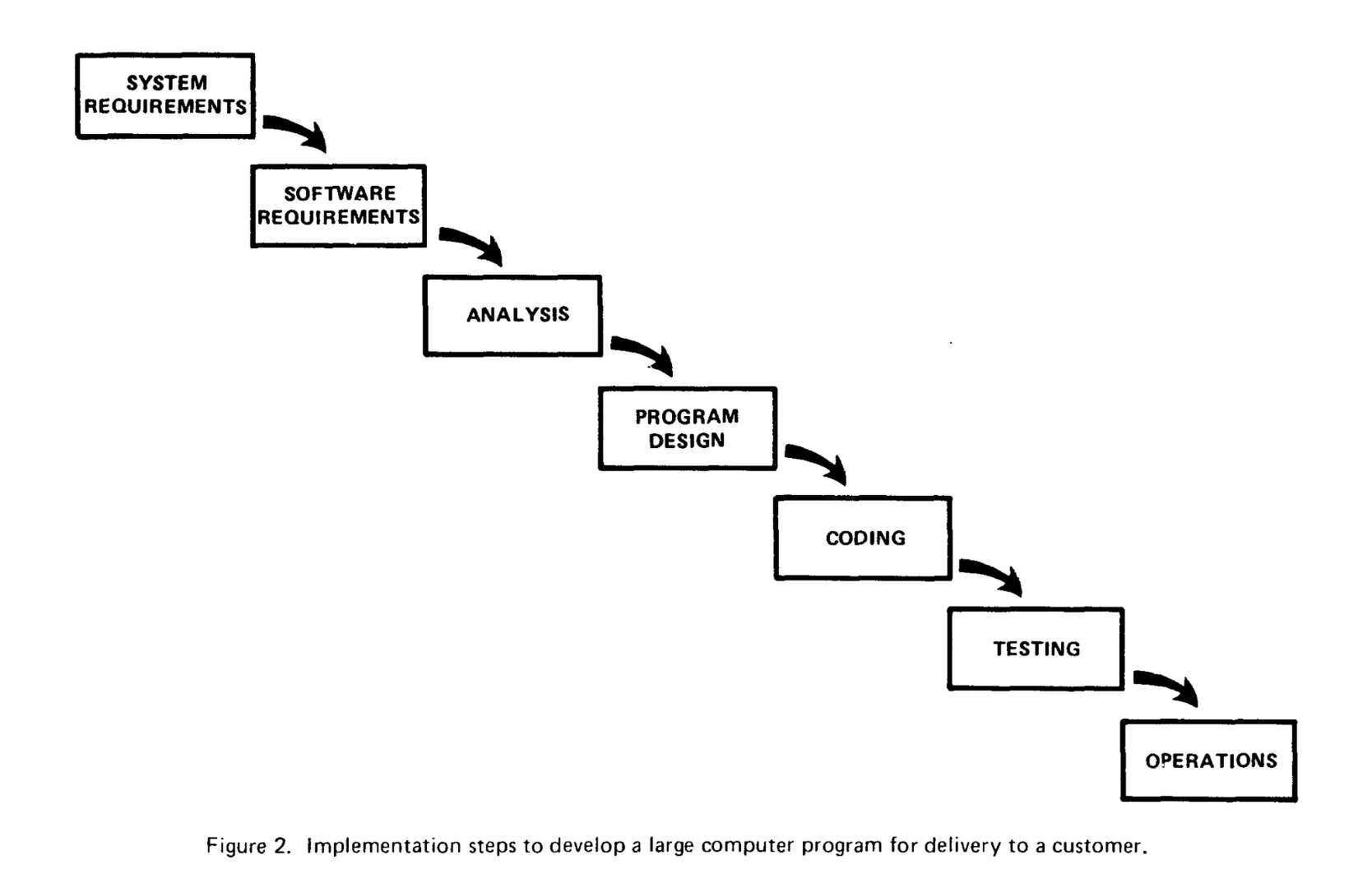

Omitting. In a podcast episode (audio, transcript), I detailed a process by which Winston W. Royce’s 1970 paper “Managing the Development of Large Software Systems” was a careful explanation of relationships between various software artifacts. He drew classic box-and-arrow diagrams to summarize his results:

Click to enlarge.

(Note that even this cluttered version leaves out some important relationships.)

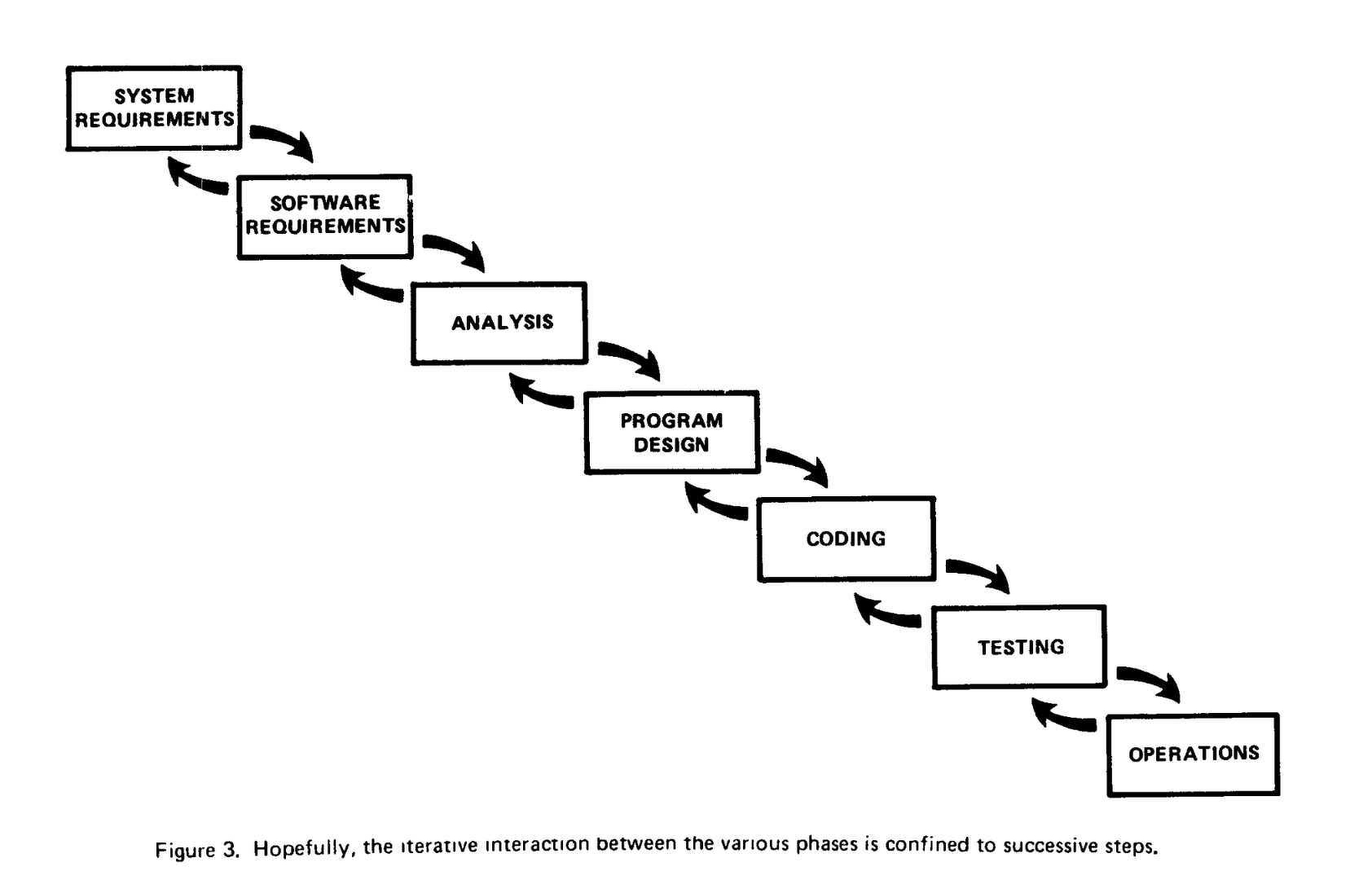

This number of relationships proved too unwieldy, so people quickly came to ignore many of the relationships. Heck, even the following picture proved too complex:

Click to enlarge.

There are two types of links, forward and back, which represent (roughly) work and rework, respectively. But even that complexity was too great, so what was for many years the default software development process became modeled like this:

goop Click to enlarge.

That model did not work well.

I claim that:

-

A love for simplicity is common – whether or not the topic is intrinsically simple.

-

Simplicity is but one aspect of the [essentially contestable concept](essentially contested concept) of “beauty.”

-

Structuralist models of reality lend themselves to node-and-edge diagrams (as with the two I gave above).

-

Because node-and-edge diagrams are visual, they are judged in part by their visual aesthetics (likely tacitly). So attributes like simplicity and symmetry are overweighted when judging whether the model fits reality.

-

As a result, structuralist (relationship-focused) models will be more prone to overdoing simplicity than other models, and they should be judged with this in mind.

Onward

When I talk about structuralist models (a category in which I include scientific formalism like the methodologies of Popper and Lakatos as well as uses of mathematical formalism.

all the action is in the edges and the nodes have no internal structure. In Lévi-Strauss’s diagram, all we know of the father is the + or - annotations on the edges.

and there is nothing else that you will or can know about them.

What matters is relationships between entities, not properties of the entities themselves. The father’s character doesn’t matter in Lévi-Strauss’s theory of kinship; what matters is his relationship to his wife and his son.

This is

One of my hobbyhorses is this: anything that draws your attention is drawing that attention away from something else. (For example, checklists make you better at seeing the things on the list and worse at seeing things that are not.)

The focus on relationships in structuralism means that details of the things-being-related are omitted. If you describe structures using the trusty node-and-edge diagram (as I did twice above), all the action is in the edges and the nodes have no internal structure. In Lévi-Strauss’s diagram, all we know of the father is the + or - annotations on the edges.

It’s akin to the definition of groups in mathematics. There are three entities: a set of things (integers, say), one operation (addition) and an identity (0). There are three formulae that mention those entities, and there is nothing else that you will or can know about them.

People (at least WEIRD people) tend to judge theories by their aesthetics. Here’s Paul Dirac:

In his Edinburgh lecture, Dirac argued that what characterized the deepest and most successful theories of modern physics was mathematical beauty, a concept that was not, in general, the same as simplicity. Newton’s classical law of gravitation is about as simple as a fundamental law of physics can be, involving only ordinary numbers and simple mathematical operations such as multiplication, division, and squaring. On the other hand, Einstein’s law, as given by the equations of general relativity, is expressed by a complicated system of equations that involve mathematical quantities called tensors. No doubt Newton’s law is simpler than Einstein’s; but Einstein’s theory is better, deeper, more general, and nearer to the truth than Newton’s. Dirac’s advice to his fellow theoretical physicists was to strive towards the element that, more than anything else, characterized Einstein’s theory, namely mathematical beauty. […] Simplicity was worth considering too, but only as subordinate to beauty. [my emphasis]

My take is that beauty is an essentially contested concept – that we will never arrive at a consensus definition (or understanding) of beauty.

I further think that people who judge designs, or theories, or arguments by simplicity are only using that as a synecdoche for a more general sense of aesthetics of which simplicity is a part. For example, beautiful things tend to have symmetry, and I think that influences judgment, especially when looking at node-and-edge graphs/diagrams – gabriel – That’s relevant to structuralism because its results lend themselves to, and are often presented with, classic node-and-edge diagrams like the two I used above.

Unlike Dirac, I think aesthetics isn’t a particularly good source of evidence. Because so many disagree, I find it useful to think about how the aesthetics of a theory can lead one astray,

Another, more controversial idea is that aesthetics isn’t a special guide to the truth. Or, if it is, it’s one that too many people assign too much weight to.

You may notice that I use “aesthetics” where a lot of people would use “simplicity.” I’m with That is, I agree simplicity is only one facet of the of “beauty”. I differ from Dirac in that expect

For example, I disagree with the physicist Paul Dirac [check]: Simply Dirac, chapter 9

Structuralist theories are often expressed with the classic node-and-edge graph/diagram, where the nodes are entities and edges represent relationships. Structuralists are predisposed to focus on the edges rather than the nodes. Often, the relationships are taken to be complete in the sense that everything worth knowing about