Human beans love thinking in binary oppositions. That is often way too crude for serious understanding and problem-solving. I offer a complex visual metaphor that might help you and others push against the binary reflex.

Reminders

A number of years ago, I made some “An Example Would Be Handy Right About Now” stickers.

They were a punchy way of shifting a conversation that was going nowhere because people were fixated on airy abstractions and definitions of terms. By saying the slogan, I could (sometimes) shift the conversation to a discussion of particular concrete details. My experience as a software tester had taught me that even just searching for examples (and counterexamples) tends to make problems leap out at you.

I used to hand the stickers out to team members at consulting clients. Some put them on their laptops. When conversations got bogged down, someone could point to the sticker, say the “An example would be handy…” words, and the conversation would often shift. It’s funny that a laptop sticker would carry with it more authority than just the words of a tester. I can only echo the words of the narrator of “Bartleby, the Scrivener": “Ah Bartleby! Ah humanity!” I was told at least once that just mutely pointing at the sticker on someone’s laptop would do the work. As software researcher Warren Teitelman once said in reply to an audience question: “People need more often to be reminded than informed” (paraphrased from memory). The visual reminder was needed to kick people out of a conversational rut.

So let me develop a sticker-suitable diagram that might serve the same purpose for fruitless discussions that center on binary distinctions. My design skills are, to put it mildly, not great. If you want to do a better job – I’m sure you can – have at it. I hereby place all images on this page in the public domain, except for the images not due to me (noted at the end of the post). CC0 1.0 Universal “By marking the work with a CC0 public domain dedication, the creator is giving up their copyright and allowing reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, even for commercial purposes.” I know, I know, it’s presumptuous to think anyone would want to, but a guy can hope, can’t he? If you want me to distribute your sticker, I will.

Binaries

Good/evil, left/right, mind/body, man/woman, child/adult, handsome/ugly, liked/disliked, loyal/traitorous, theory/experiment, academic/pragmatic, particle/wave, etc. etc. etc. Binary distinctions are a way of life for us. There are two key problems with that. To show the first problem, I’ll start with an easy target, the statistical binary significant / non-significant.

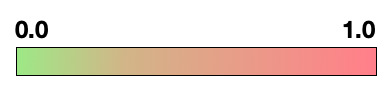

The reality is that a probability ranges from 0.0 to 1.0:

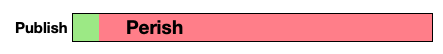

However, scientific culture has decided that there’s a threshold for a statistically significant probability, the famous p < 0.05:

That makes thinking easier. You don’t have to look at a p value of, say, 0.09 and interpret that number in the context of the experiment in order to make the practical decision of accepting that the measured effect is real (rather than random error), and thus potentially useful to build upon.

However, it’s not making thinking better, because you’re applying a distinction that doesn’t exist in nature. For purely pragmatic reasons, you’ve created a sharp binary, two different categories instead of a spectrum:

Indeed, I’d argue that, in such cases, it’s more descriptive of the actual thinking to stop hinting at the underlying spectrum:

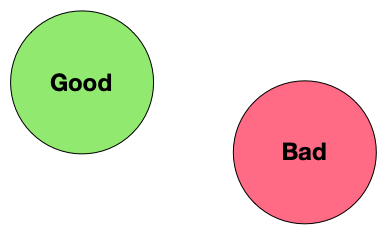

I’ve labeled the circles “good” and “bad” because that’s the second of the two problems: we have a strong habit of assigning moral or emotional valence “Valence, also known as hedonic tone, is a characteristic of emotions that determines their emotional affect (intrinsic appeal or repulsion).” – Wikipedia I’ve recently become strangely fond of that word. “Salience,” too. to the two categories. Not only are the categories disjoint, one is better than the other. I’ve indicated that with the coloring and also by placing “good” higher than “bad.“ Humans tend to think of “up” as the direction of “good.” That’s why heaven is up. That’s why someone might leave their job to pursue a “higher calling.” And so on. See Lakoff and Johnson, Metaphors We Live By.

Come to think of it, the picture shown above suggests good declining into bad (since change happens in time, and time flows left to right for me, a native English writer). It’s more appealing to show progress rather than decline:

That’s better.

In the jargon, one half of a binary distinction is “privileged” and the other is “marginalized.” Because of that, such distinctions are often called “binary oppositions,” building conflict into the morality play.

It’s not surprising or a problem, really, that scientists privilege statistical significance over non-significance: significance means they accomplished their goal, which is good.

But for other oppositions, things get more problematic:

- mind/body

- theory/experiment

- academic/pragmatic

- man/woman

There’s some debate, I understand, whether the direction “right” has historically been privileged over “left.” All I can say is that I remember my dad (born 1920) telling me his brother Richard was born left-handed. The schoolteacher in their small East Prussian peasant village forced Richard to write right-handed. Not for any practical reason that I recall, but just because that’s the right way to write, the right way for a person to be.

My claim is that binary oppositions often trick you into asking the wrong question. Consider the good/evil opposition. In life, the problem isn’t so often identifying whether x is good or evil but whether action x is a better choice than action y. The binary opposition reifies

“To regard or treat (an abstraction) as if it had concrete or material existence.” evil, makes it a thing of its own, not an attribute of an action in a context. That leads to crude moral reasoning applied to situations where such is worse than useless.

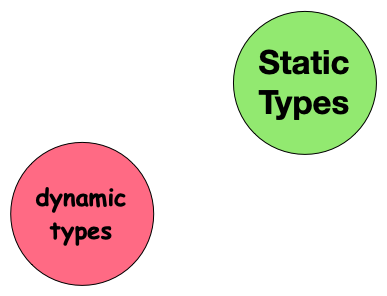

I suspect such playing favorites is too innate to avoid. Maybe the best thing is to lean into it. For example, if you’re writing about typing in programming languages, and you personally wonder what’s wrong with people who prefer dynamic typing, maybe you should be explicit about your feelings with a diagram:

Or maybe print your preferred term in green text and the other in red text. This will reveal to your reader that (1) you’re human, thus (2) biased, but that (3) you recognize it. More importantly, the silliness of doing so might make you reflect on whether you prefer your position because you’ve reasoned yourself into it or that you’ve reasoned yourself into it because it’s what you prefer. Interesting how smoothly that sentence makes a binary distinction between reason and preference, including tacitly implying that reason is the better of the pair. Note that the privileged/marginalized distinction is similarly artificial. That something is privileged is way less important than how privileged it is and the way that privilege manifests in practice.

Actions

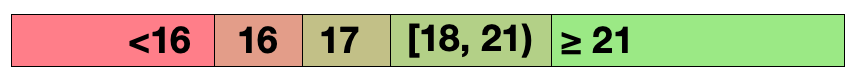

Let’s move to another binary opposition: child/adult. In my country:

-

When it comes to drinking alcohol, you become an adult at age 21. (When I was in college, it was 19, except it was 18 next town over. There were more bars in that town.)

-

When it comes to voting, you’re an adult at 18. (It was 21 until people got upset 19-year-olds were adult enough to kill Vietnamese but not mature enough to be trusted with a vote.)

-

The age of consent (for sex) in my state (Illinois) is 17.

-

When it comes to driving, “adult” means 16.

If we think of a spectrum from child to adult, the lawmakers of the great state of Illinois have divided it up into hard-edged categories:

However, all this isn’t worth much when it comes to thinking about the adult/child distinction. What underlies that diagram are the following notions:

- Adults are responsible for their actions.

- Amongst those actions are driving, consenting to sex, voting, working, and drinking alcohol. There are surely others, but these are ones worth legislating about.

- A given child will become responsible for different actions at different ages.

- Ideally, we’d allow a child to do something when he or she is responsible enough for that particular action. Since that’s impractical, we pick an easy-to-determine proxy (age) for the hard-to-observe characteristic of responsible-enough-for-X.

An attempt to roll these individual criteria up into a definition of what it means to be an adult presents all the problems I outlined in my post on essentially-contested concepts. That is, if adulthood is based on a combination of criteria, different people will weight them radically differently. To some, if you can hold down a job (age 14 in Illinois, with restrictions until 16), you’re for all practical purposes an adult. But some might retort that a 16-year-old in Illinois is adult enough to drive during the day, but not at night (between 22:00 and 06:00, but you get an extra hour on Friday and Saturday nights). Moreover, you can drive a car at 16, but you can’t rent one until you’re 21, except if you’re one of an enumerated list of exceptions, in which case it’s 18. Also, while you can have a job at 14, you can’t sign a contract until you’re 18. Evidently, there are many word-adjacent responsibilities that 16-year-olds aren’t ready for.

Others will focus on parenthood. Certainly someone responsible for a child ought to be an adult, so the age of consent should weigh heavily in determining whether someone is an adult. But in some states (not Illinois), age of consent depends on the age of your partner (so-called “Romeo and Juliet” laws). That is, you’re adult enough to have sex at 17 if, for example, your partner is 19, but not 25. Moreover, many men (at least) consider sex between a girl of 16 and an adult of 26 worse than between a boy of 16 and an adult of 26. Well, at least if the adult is a woman, where the reaction from men is fairly likely to be “I should have been that lucky!” A boy of 16 and a male of 25 is likely to get a very different reaction from those men.

The result of this is there’s no simple function is-adult? that takes an age and returns true or false. Any such function would have to weigh many variables. You might be dismissive and think “well, duh, lawyers like making complicated laws,” but such complexity is everywhere – it’s more common than the simple cases.

In practice the decision is unconscious, made via tacit knowledge (as in my story of the bright/dull cows) rather than an explicit calculation. All that matters is that you personally have some means of deciding adulthood that produces results consistent enough with those of the people whose opinions you care about (definitely including judges).

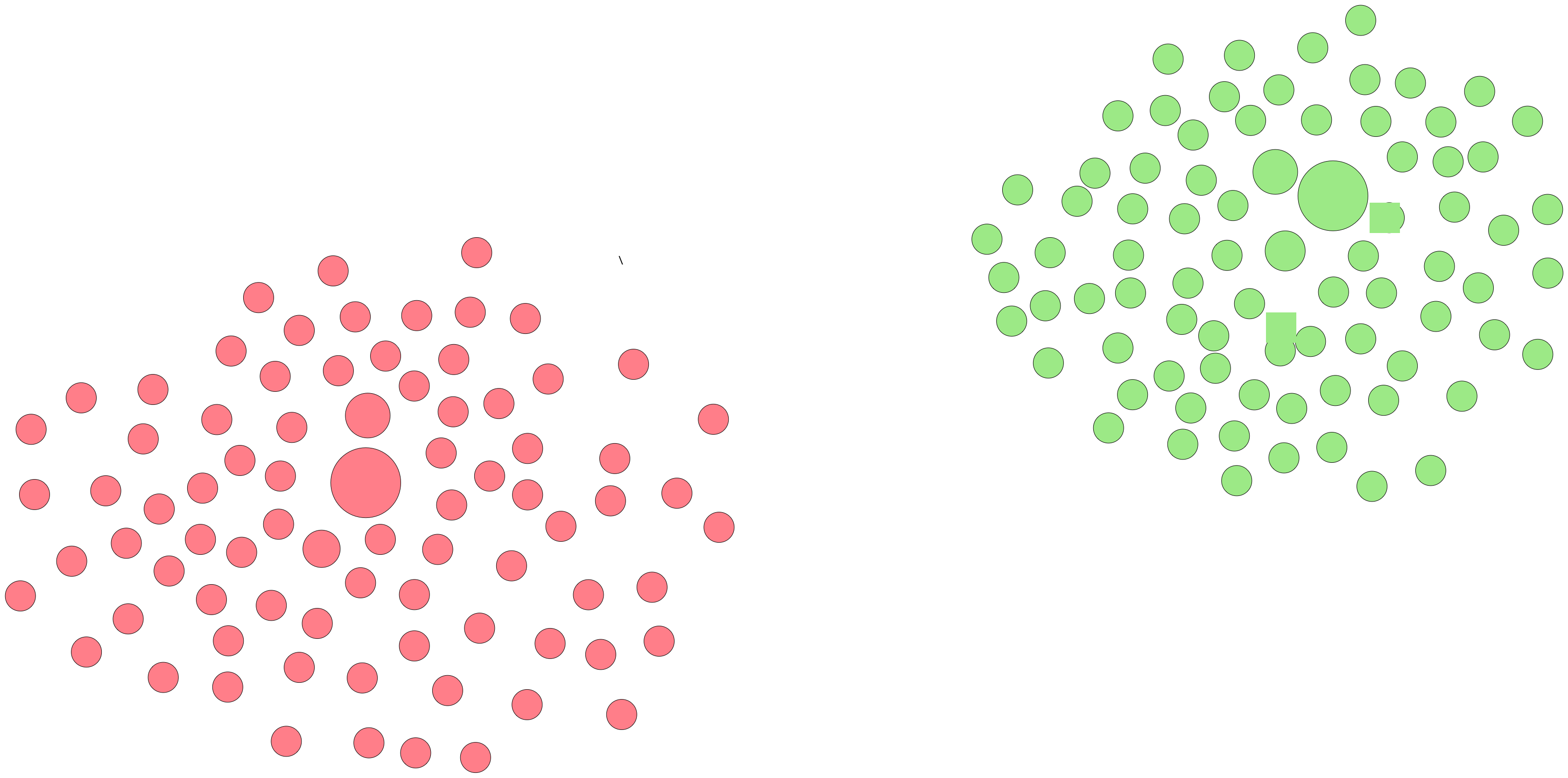

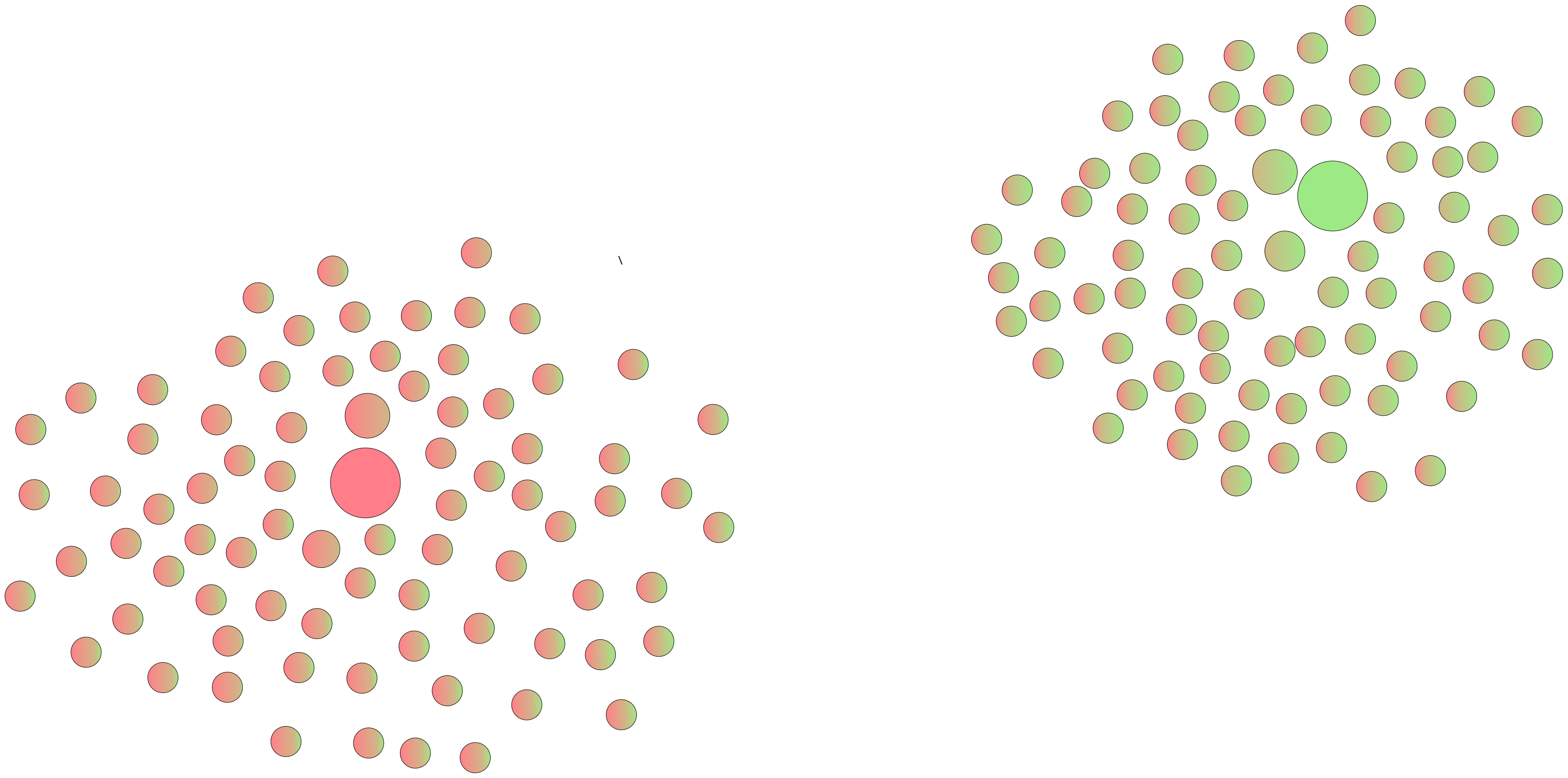

Let me represent that like this:

We still have two distinct categories. Each of the circles represents some combination of factors that go into the tacit determination that a particular x belongs in one category or the other.

You may notice that each of the circle-clouds has one circle that’s largest. I’m following here what I think is the dominant view of categories in the human sciences (though not necessarily in philosophy):

Prototype theory is a theory of categorization in cognitive science, […] in which there is a graded degree of belonging to a conceptual category, and some members are more central than others. – wikipedia

bird. For at least European and North American people, the prototypical bird is the small brown songbird. The more different a bird is from the prototype, the less “birdlike” it is. Ostriches are weird birds because you rarely see their wings, and they don’t fly.

Except that people often describe penguins as flying. They just use a different medium than air: water. How, then, should we weight the various kinds of flight against the verticality of posture? We usually evade the issue by just following the societal consensus of grouping all three animals under the category “bird.” Or, if we need to justify ourselves, we appeal to the authority of biology and its “tree of life” – which is a social move in itself. After all, biologists also have disputes about classification.

So let’s visually indicate the gradations of category membership by shading different circles differently:

All images can be clicked to enlarge them in a new tab.

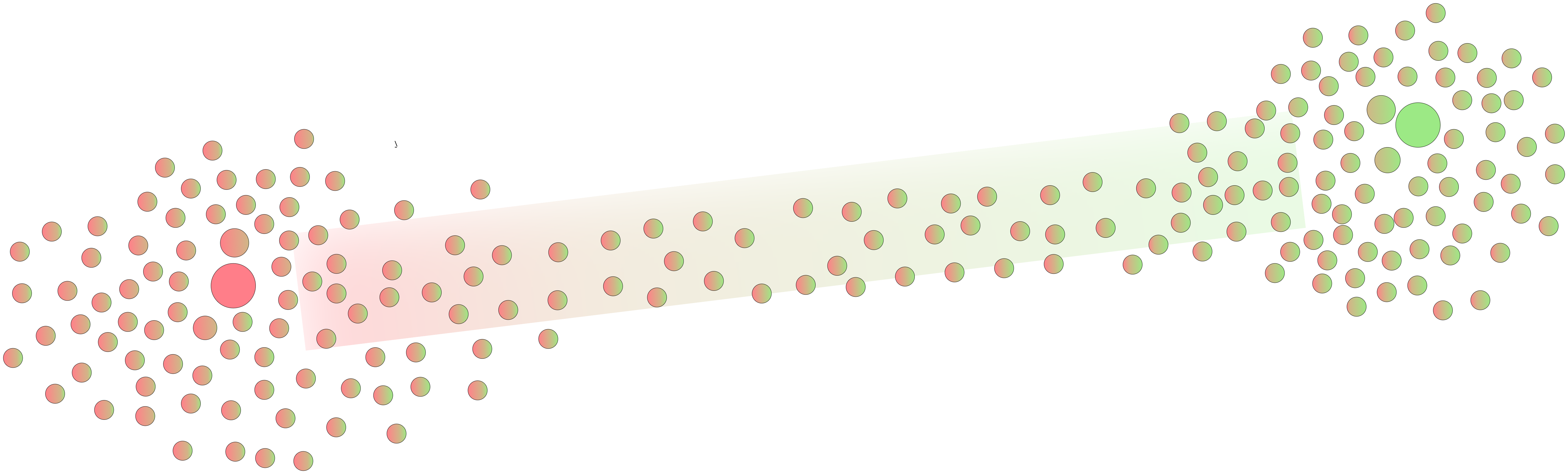

I hope placing the simple linear spectrum in the context of the circle-clouds raises makes the question “linear or multi-dimensional?” more salient. Told you I was obsessed with the word. Something that’s more salient is more noticeable, more relevant in context. It stands out.

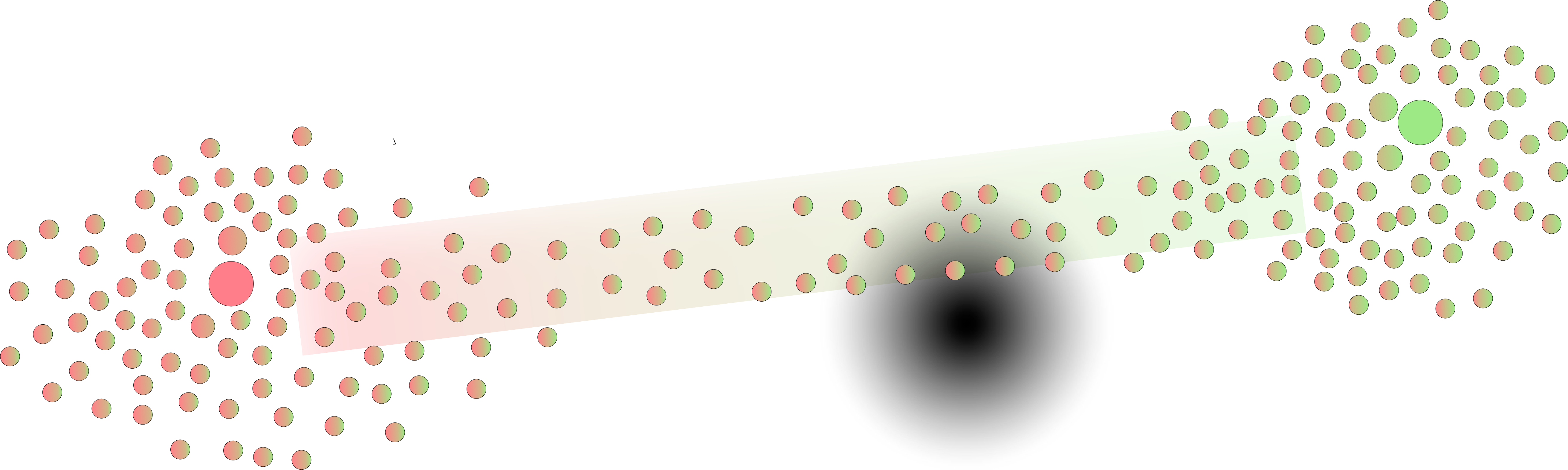

As a final addition, I place a different kind of cloud on the diagram:

What this signals is that, yes, we’re bilaterally symmetrical and that does predispose us toward either/or thinking, but there are actually often more than two sides to an issue. By focusing on the big red and green clouds, perhaps you’re ignoring something important. If you focus too much on the binary distinction between plants and animals, you’re more likely to consider fungi as funny (penguin-like) plants rather than what they are: something completely different.

Wielding the sticker

Credits

My CC0 1.0 Universal license does not apply to these images:

-

The picture of the wren is in the public domain, but I didn’t put it there. It’s been more than 100 years since the author’s death. Wikipedia Commons page

-

The picture of the ostrich is by Nicor, CC BY-SA 3.0. Wikipedia Commons page

-

The picture of the penguin is by Bl1zz4rd-editor, CC BY-SA 4.0. Wikipedia Commons page

Note that it does apply to the “Example” sticker. If you love something, set it free.