A Zettelkasten is a particular sort of hypertext document as well as a technique for creating it. My aim in this post is to give you an understanding of a Zettelkasten document – its parts and its whole – and, more importantly, show something of what it’s like to work with a Zettelkasten. A Zettelkasten will appeal to some people much more than to others, and I’d like you to be able to predict where you’d fall on that spectrum. Presenting vignettes of my own work (lightly fictionalized) is the means I’ve chosen.

Comparisons of the Zettelkasten to what I earlier called a “wiki traditional” hypertext document will come in a later post.

I’ve spent less than two months in near-daily Zettelkasten use. Which is not much time, especially since Niklas Luhmann (an originator of the technique) says, “The Zettelkasten needs a couple of years to reach critical mass.“ Niklas Luhmann, “Kommunikation mit Zettelkästen” (1981), translated by Sascha Fast. So why do I feel justified in writing this post?

-

It happens that when I’m emotionally and intellectually sympatico with a technology or work process, I have a knack for absorbing it and explaining it to outsiders, even while I’m still a novice myself. That is, I have a track record with this sort of thing that encourages me to be immodest in this case.

-

Novices have certain advantages in explaining to other novices, most notably that they remember what it’s like to be a novice. They have an advantage in knowing – viscerally – what novices need to know. For experts, the feeling fades.

-

Cunningham’s Law: “The best way to get the right answer on the Internet is not to ask a question; it’s to post the wrong answer.” With luck, I’ll learn faster as experts correct me.

If I whet your interest in Zettelcasten, let me recommend Bob Doto’s A System for Writing and Sönke Ahren’s How to Take Smart Notes. Doto’s book is more nuts-and-bolts. See also zettelkasten.de for various resources, including a forum. Those three sources by no means exhaust what’s available to you, but they’re what I’ve leaned on.

Contents

- A bit of history

- Who is a Zettelkasten for?

- The anatomy of a note

- Adding notes (simplified version)

- Adding and using notes (creative version)

- A peculiar summary message

A bit of history

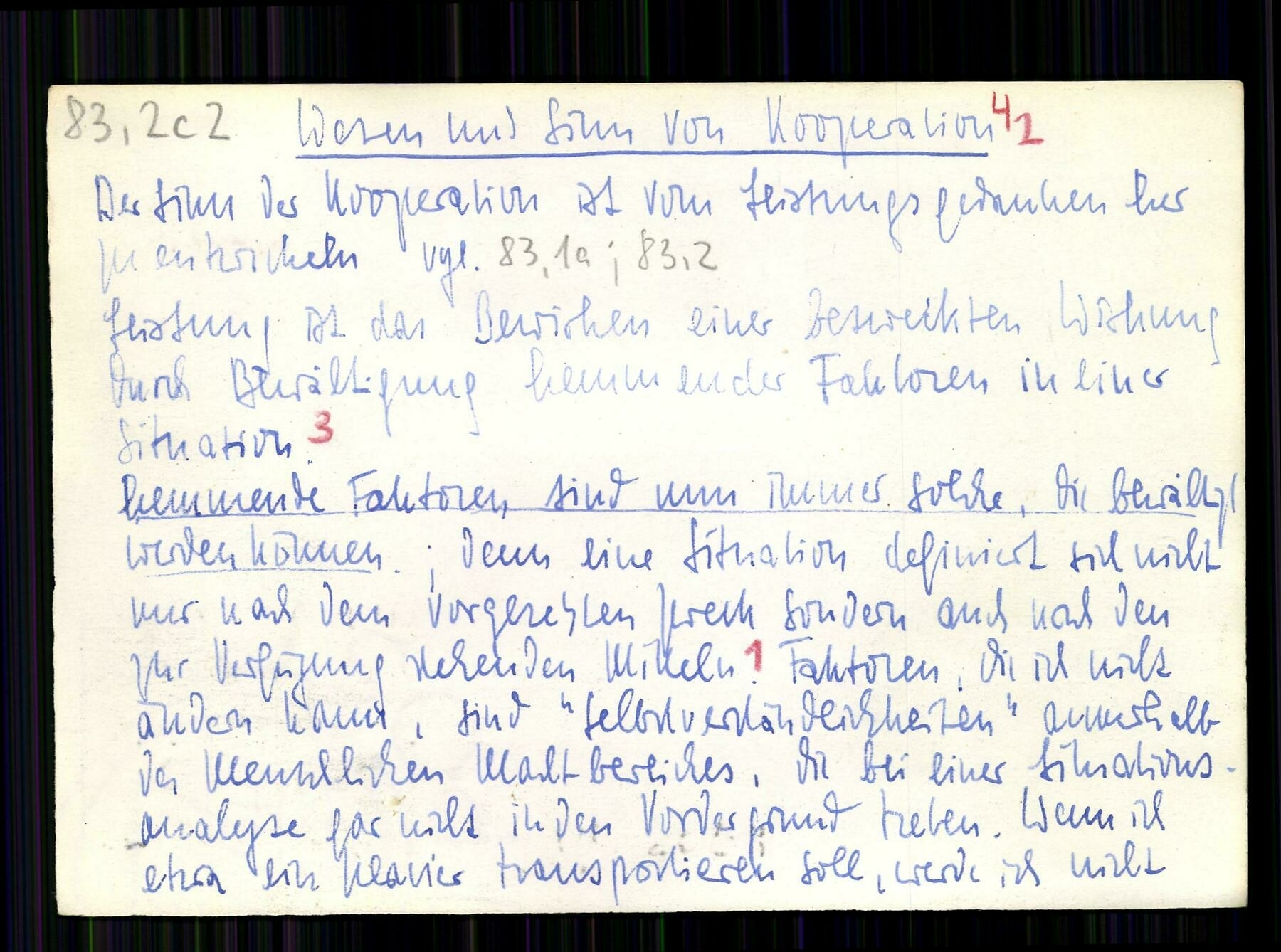

A Zettelkasten is a particular kind of hypertext document. The word literally means “note box” or “slip box,” because that was the physical manifestation of the original Zettelkasten: a set of some 90,000 note cards written by the German sociologist Niklas Luhmann over a period of 46 years. Luhmann isn’t the only person who used notecards. For example, the rough contemporary Hans Blumenberg had some 30,000 cards in his physical Zettelkasten. ("Ruminant machines: a twentieth-century episode in the material history of ideas", Daniela K. Helbig, 2019) But when people use “Zettelkasten” as a jargon word, they are usually referring to techniques descended from Luhmann’s practice. His preserved Zettelkasten looks like this:

Photo of Luhmann’s Zettelkasten is from Niklas Luhmann-Archiv and is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. Sourced from

Tevin Zhang.

The Zettelkasten was Luhmann’s tool for academic writing. He was ridiculously productive, writing over 70 books and nearly 400 articles. These were apparently not the result of a hack seeking to produce as many “least publishable unit" “In academic publishing, the least publishable unit […] is the minimum amount of information that can be used to generate a publication in a peer-reviewed venue, such as a journal or a conference. […] The term is often used as a joking, ironic, or derogatory reference to the strategy of artificially inflating quantity of publications.” – Wikipedia articles as quickly as possible: he made novel and interesting contributions to German-language sociology. He credited use of his Zettelkasten for both his productivity and originality.

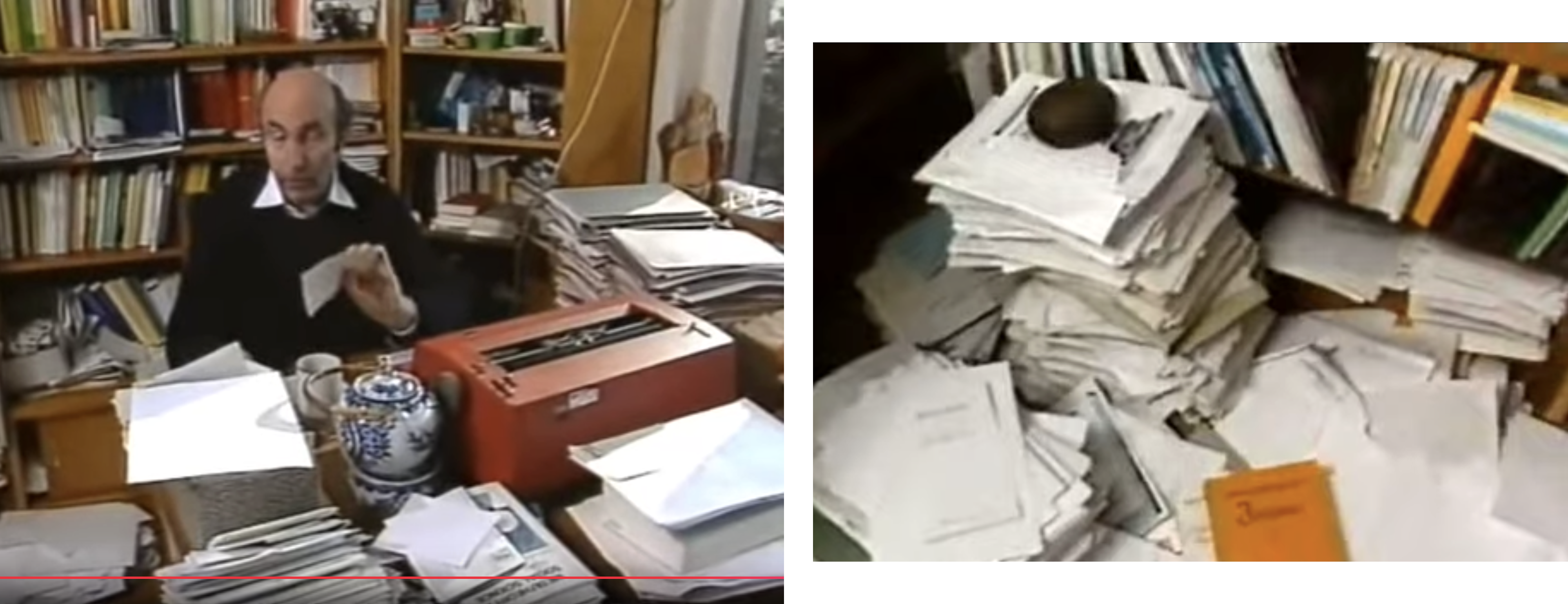

I should note that the museum-preserved version of Luhmann’s Zettelkasten gives an overly sanitized picture of his physical working environment. Below, you see pictures of his office. (Click to enlarge.)

Screen shots from Niklas Luhmann - Beobachter im Krähennest. Thanks to Christian Tietze for the pointer.

They show that he combined the traditional “piles of papers everywhere” style with his disciplined note-taking. You don’t have to be a paragon of orderliness to use a Zettelkasten. In fact, I believe a fairly high tolerance for disorder (of a certain sort) is required of a Zettelkasten user. The need to combine discipline and acceptance of disorder reminds me of Agile software development in the days before the industry took a giant Seeing Like a State sledgehammer to it, but that’s a comparison for another time.

Who is a Zettelkasten for?

A Zettelkasten is primarily a writer’s tool.

Its prototypical use is by someone who spends a fair amount of their life writing nonfiction long-form narratives (articles, blog posts, books, and so on).

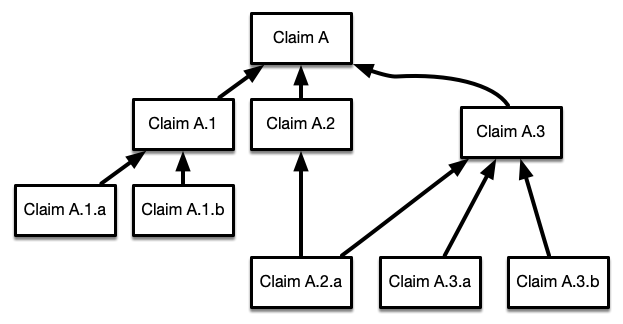

The core purpose of a non-fiction narrative is to argue persuasively for one or more claims. The justification for a claim may be other subclaims, which must themselves be justified. This can presumably continue until it bottoms out in claims that won’t be justified (axioms, presumed axioms, and claims you want to avoid addressing because you’re not so sure of them).

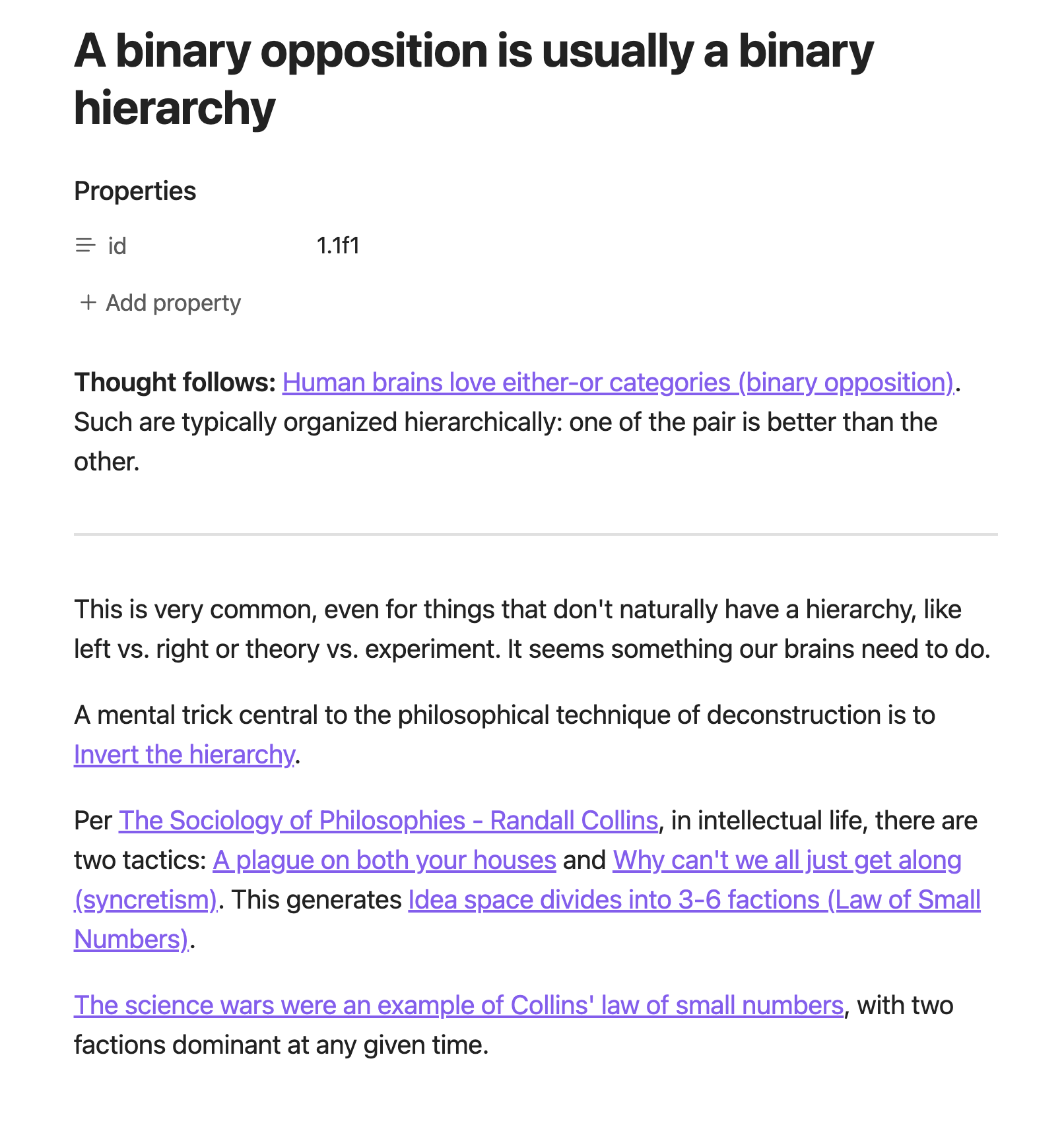

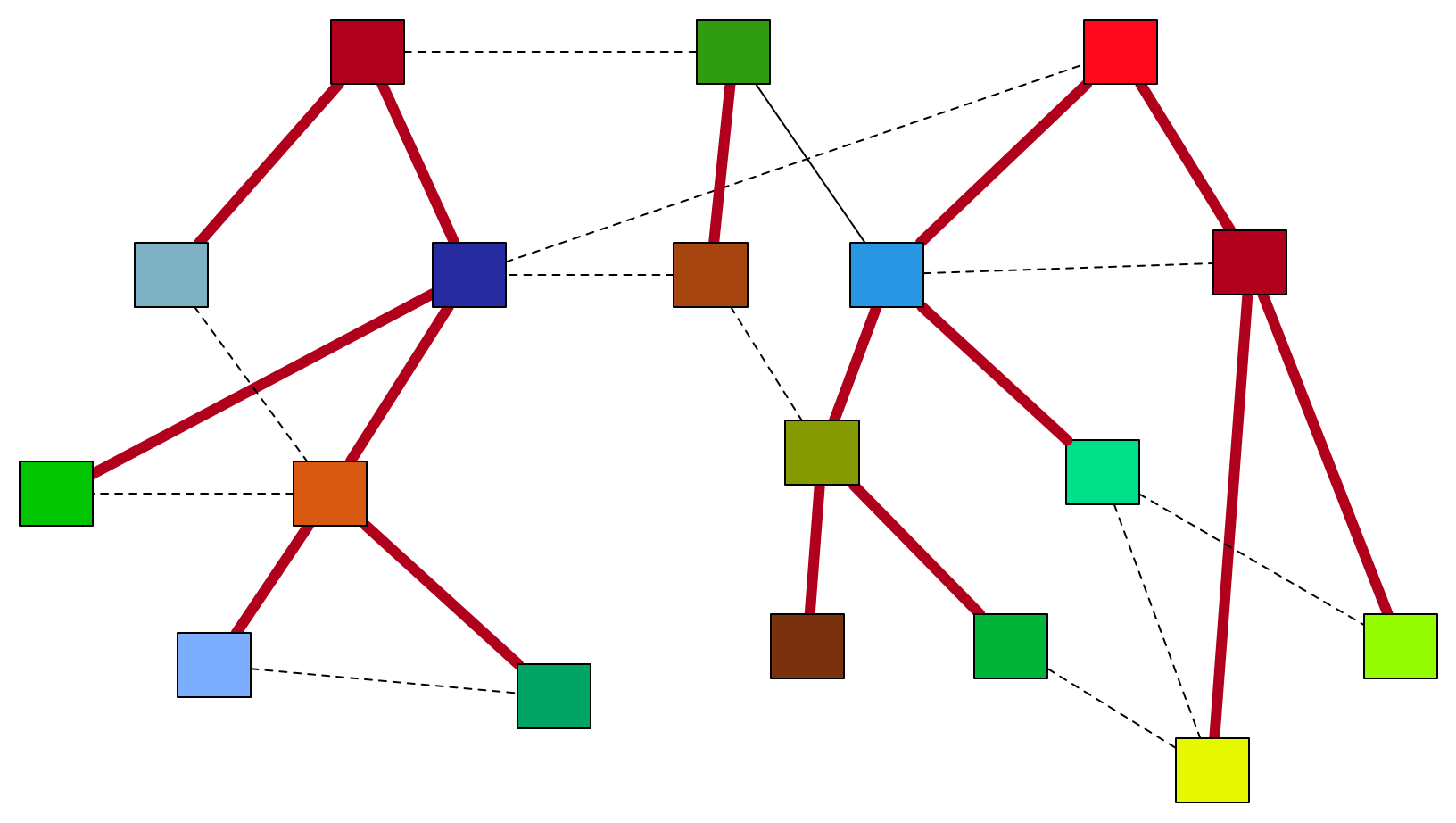

You end up with something like a tree:

For all images, including those in this sidebar, you can click to enlarge into a separate tab.

The writing’s not finished until those claims are linearized into a sentence-after-sentence narrative, including adding a lot of connective tissue. How you organize the explanation – bottom up, top down, some combination – is up to you.

Good narrative writers use various devices to engage and persuade the readers. Those often require breaking the linear claim-by-claim structure to include implicit and, perhaps, explicit back links. That’s a fascinating subject, but it has nothing (I think) to do with the Zettelkasten, so I’ll say no more.

A Zettelkasten stores notes that the writer creates by reading various documents and writing down claims they want to remember. Later, some of those notes are reread and a selection of claims are used in a narrative.

Notes can also contain claims sourced to no one but the writer. That is, you’re allowed to have an idea, write it down on a note, and stash it for later use.

The writer typically makes no concessions to any other reader. The intended audience has one member.

Success criteria

An academic’s job is not to read old claims from a bunch of sources and repackage them in different combinations with a different order. Academics are supposed to invent new claims and argue for them.

New claims often come from juxtaposing claims that haven’t been so linked before. “If (1) fast feedback is important for design, and (2) testing can be thought of as providing not just bug reports but design feedback, then… (new) I claim testing can be done in a certain way that produces a tighter feedback loop.” (It’s both putting claims 1 and 2 together, and the devising of “the certain way” that make up the intellectual contribution.)

The creative process is not understood well enough to be mechanized, but it frequently involves some thinker having one or more claims active or “ready to mind,” adding a new claim to mind, and saying “Eureka!”

The Zettelkasten has to store claims as notes and retrieve them, and that needs to be reasonably easy. However, I’ll be bold and say that the main goal of a Zettelkasten is to be a serendipity machine. That is, it should make it more likely that the writer will, at some point, mentally juxtapose two or more notes and get a new idea.

The anatomy of a note

In the case of an electronic note, there’s no such constraint, but I think people generally favor making notes terse enough to be visible all at once.

Below: two of my cards

The title

Luhmann used unique alphanumeric labels to identify cards. (More on that later.) Modern hypertext style encourages giving notes titles. Wiki-traditional titles are words or noun phrases – names of things (like Zettelkasten or Platonic Idealism or Karen Chekerdjian).

Zettelcasten titles are usually sentences, and usually what I think of as factual claims. Some of mine:

- Concepts have fuzzy boundaries.

- The brain has many action-oriented models.

- Thinking hard doesn’t burn much more energy than just lazing around.

- Derrida was entranced by recursion.

Note that titles aren’t necessarily passive-voice “to be” statements (“Bourbaki was a French collective of mathematicians”). They can be rather more active: “Human brains love either-or categories” or “Visual perception fluctuates.”

Titles (the claim the note makes) are to be atomic, about a single idea. There is no objective measure of a note’s atomicity. Since the Zettelkasten is for a single person, that person will form their own subjective understanding over time. For me, at this time, I think of a claim as atomic if I can imagine using it in its entirety within a narrative. If I’d have to leave behind part of what’s claimed, it’s really two claims that should go on different (probably hyperlinked) notes.

The text

At the moment you came up with the title, you have a pretty good idea of what you mean by it. But a Zettelkasten note might next be encountered a month, a year, a decade after it was written. It is very likely the title will not be enough to remind you of what you meant.

So you need to write more sentences about the claim. But it’s extremely likely you can’t write enough to be sure you’ll remember what you meant. Alternately, you could think of reading a note as causing you to re-generate a thought you’ve had before – or something close enough, anyway. If you tried, you’d spend all your time writing notes and no time using them.

So you’ll settle for a few sentences. Making the claims narrow – atomic – will help make them sufficient. Including links to related claims will also help jog your memory.

The links

Links in a note go to destination notes that make related claims. (Mostly.)

Because the titles of the destination notes are full sentences, and a link almost always shows the text of the destination’s title claim (as shown in the sidebar images above), it’s tempting to just list them in the body of the note:

I have enough self-knowledge, though, to realize such sentences will not be enough when I revisit the note in a few months. I’ll need more context, more explanation of why I thought that claim was relevant to this one. So I add more text:

“If Structuralism is a mental style, does that push against understanding the sort of “order through fluctuation” described below?”

“Another is that clusters maintain state. (See Neural clusters are self-reinforcing). We know from distributed systems that maintaining replicas is expensive.”

“It’s true that chemistry is physically determined by the laws of physics, but is it useful to think of it that way? Would you rather be correct or effective?”

Note: going forward, I don’t want to cause confusion about when I’m talking about the title (text at the top of a note) and when I mean a link to a note with a particular title. So I’ll call the latter “title-links” and, when I can, I’ll show them highlighted as links, even though they aren’t actual links into my Zettelkasten. (They go to example.com.)

Important

Even given several sentences, I may still find the relevance of a link obscure later. So, when I figure it out, I change the note. This is not dissimilar from the advice I used to give programmers during my consulting days:

As you work on your current task, you’ll be browsing through existing code. Make note of what’s awkward about it – a function in the wrong place, a bad name, a function that does too many things, whatever bugs you. At the end of a task (twice a day, say) spend some time fixing some of those things – half an hour, say – before you move on.

Tweaking notes and adding links is the same as cleaning up code: constant modest improvement.

Labels

In a hypertext document, you just click on a link and poof you’re at a new note. Luhmann had to work with physical cards. How did he get from one card to the other?

(This may seem irrelevant in the digital era, but bear with me.)

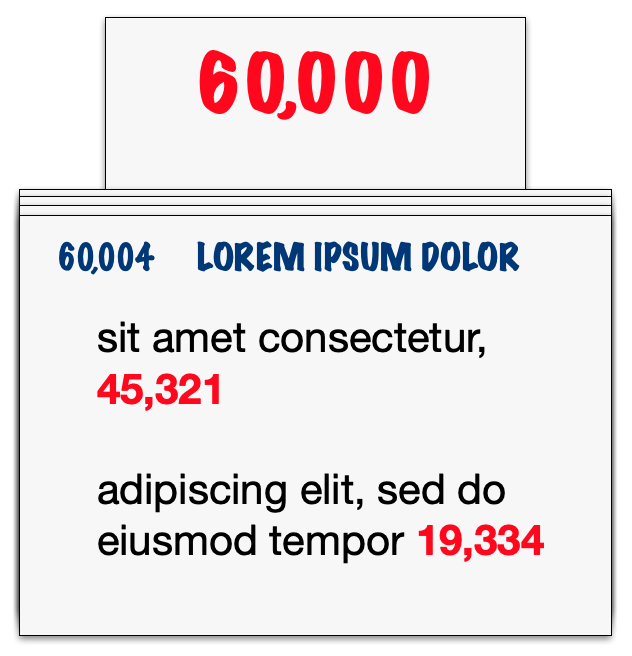

An inadequate solution would be to number the cards and keep them in order. Maybe you put some cards in sideways (portrait instead of landscape) every five thousand cards or so, numbered with the next card, to make searching for card 63821 easier. It wouldn’t be too hard to come close to 63821 if you know where card 65001 is, and then you’d need a few more tries to get to the target card.

The problem comes in adding new cards. What if you later have an idea very relevant to 63821? If your practice is to add cards to the end as you think of them, many cards will be far away from conceptually related cards, meaning following every link is going to be a search. Yuck.

But you’re certainly not going to add the new card as 63822, then increment the old 63822 and all cards following it.

Instead, you need a way of labeling cards that allows you to add a new one next to an old one without having to change old cards' labels. The solution is to establish a conceptual tree structure for the linear set of cards.

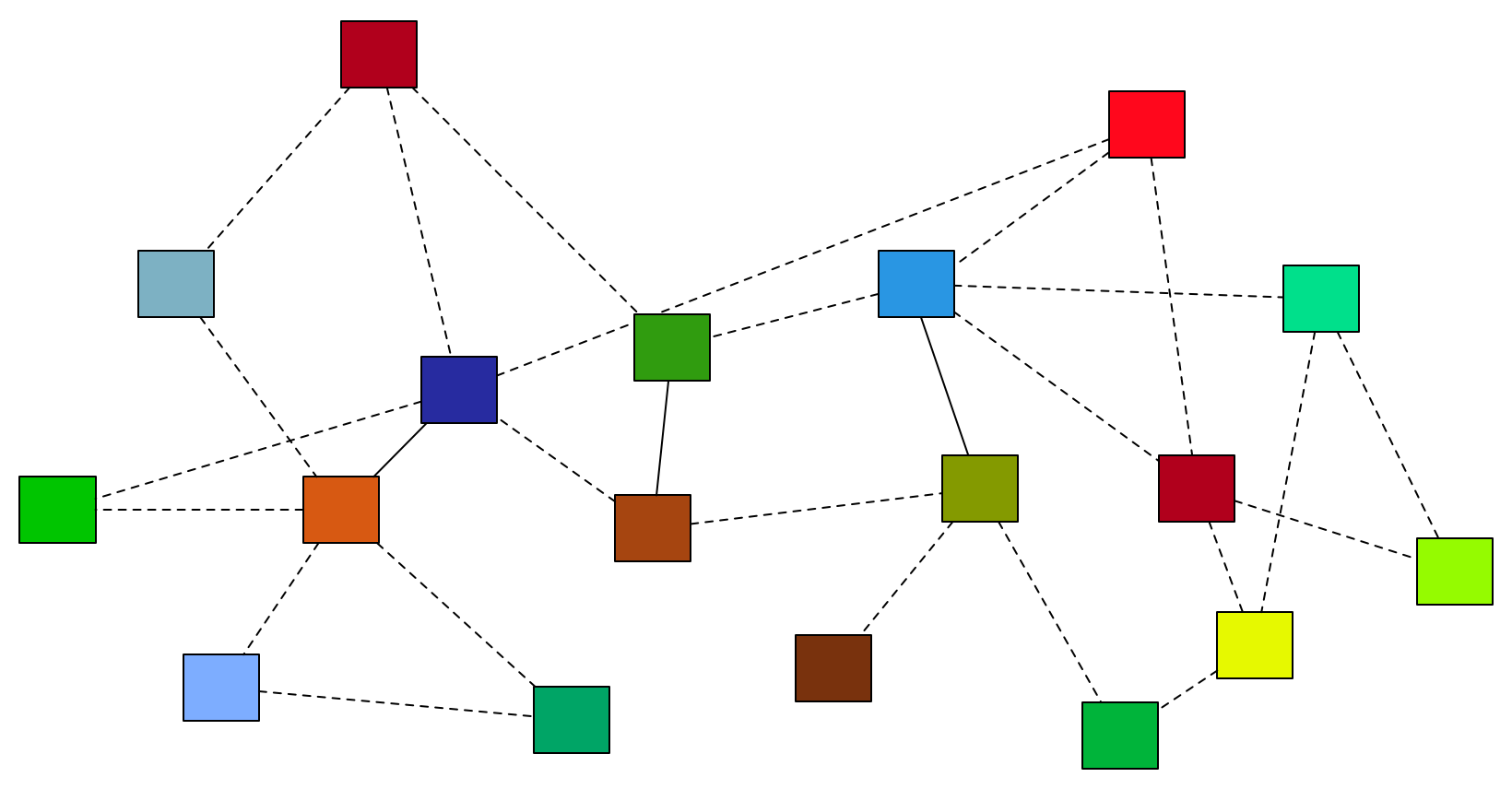

That is, imagine we start with a highly-interconnected graph:

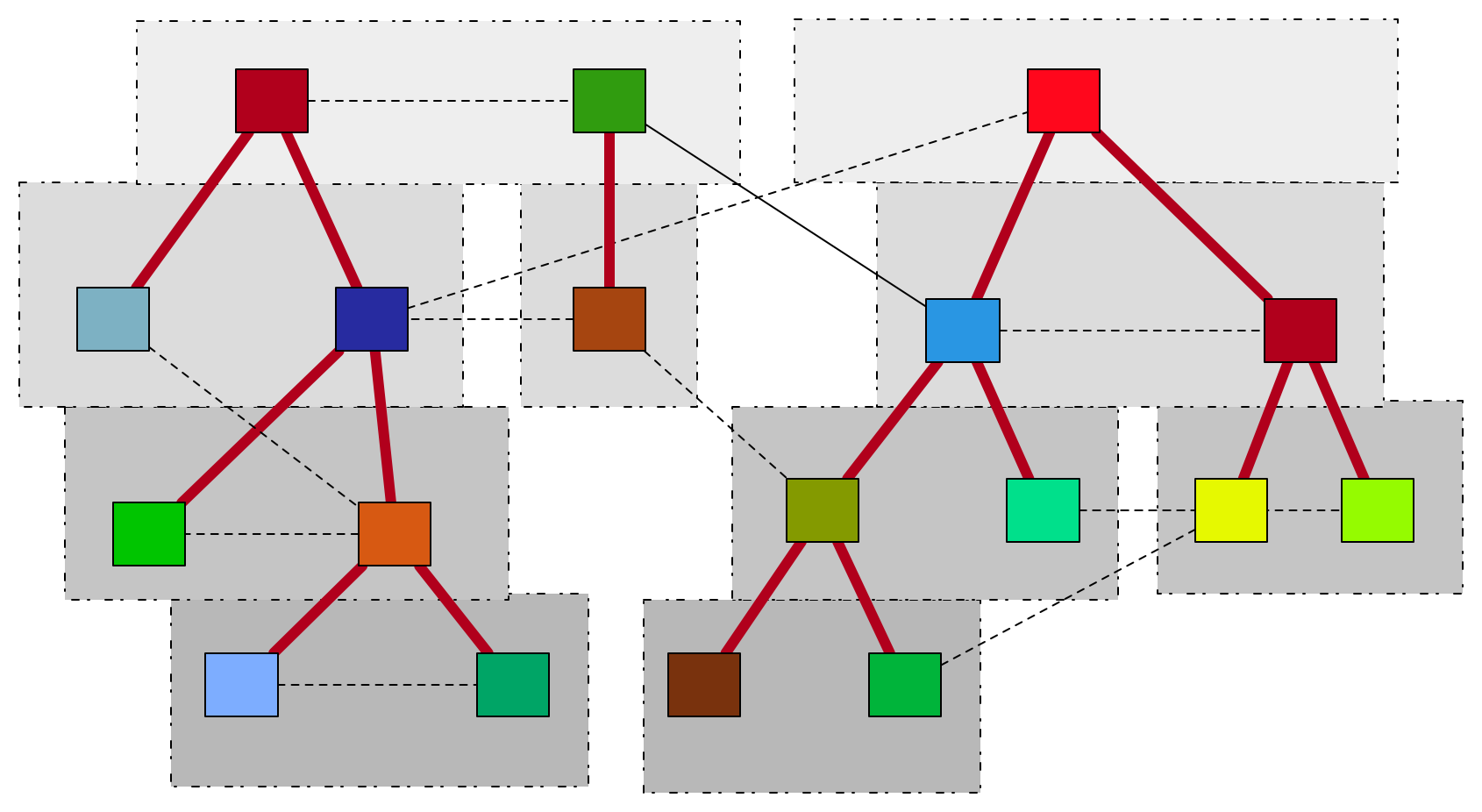

But now, certain links are treated specially by overlaying a tree structure (a spanning tree, roughly) over the free-form linking structure:

This arrangement imposes two types of relationships on the graph. Nodes are related to their parent, and also to their siblings:

The starting graph was just a mess. The ending graph is, well… As Luhmann puts it: “The entire note collection can only be described as a mess, but at least it is a mess with a non-arbitrary internal structure.“ Luhmann 1981, op. cit.

It’s easy to add new nodes to the graph (cards to the Zettelkasten) because the labels are hierarchical. When you add a new note, you conceptually add it as a new leaf to the tree:

Its position gives you a unique label, and the label tells you where to put the new card in the card box. If you put related notes near each other in the conceptual tree, they’ll tend to be near each other in the Zettelkasten, as I demonstrate below. Technically, the tree is linearized into the card box with a pre-order depth-first search, which produces a topologically-sorted card order. Sounds way cooler than it is.

Adding notes (simplified version)

In this section, I’ll describe creating a Zettelkasten from scratch, showing how I decided where each note goes. This is a fictionalized version of what I actually did, but the titles and notes are real. I’ll pretend I was working with a physical card box, though I actually use Obsidian.

The first note

My first title was “We perceive events rather than snapshots.“ Lisa Feldman Barrett, “The theory of constructed emotion: an active inference account of interoception and categorization,” Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 2017. (Roughly, that means that the brain doesn’t constantly monitor perceptions. Rather, it treats the perceptual system as a sort of “smart peripheral” that it can ask to watch out for large-scale, compound perceptions – like when my hand is gripping a soda can firmly. When that happens, the Thinking part of the brain gets a notification of the event.)

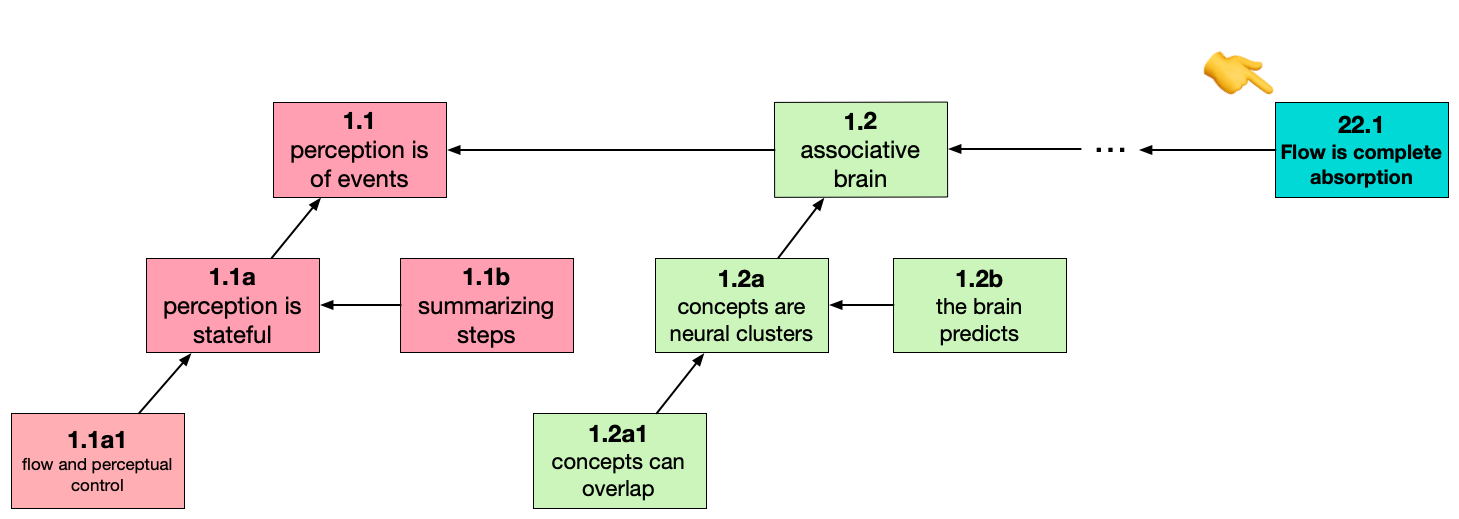

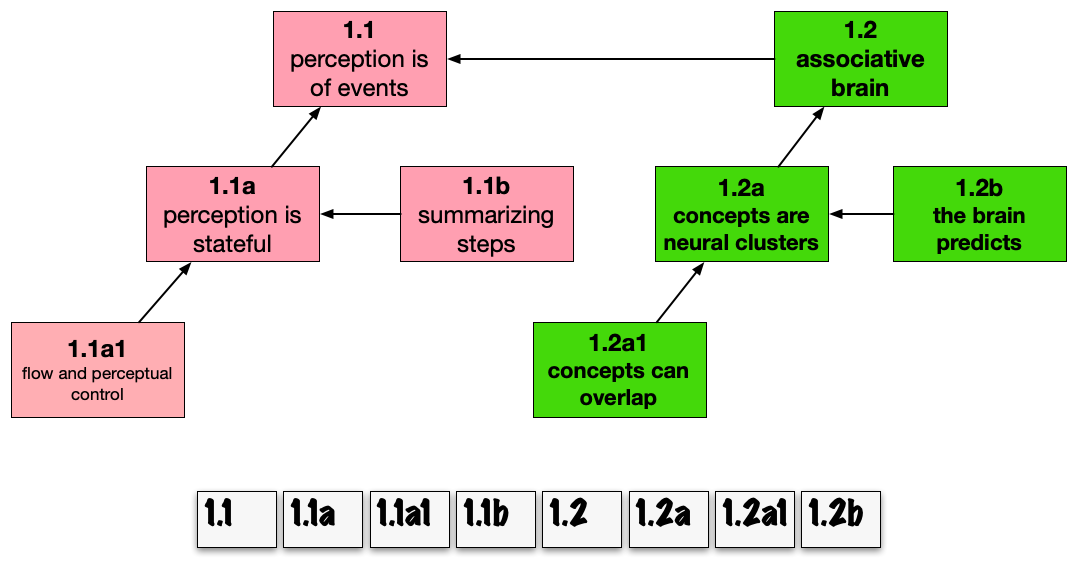

Since this was the first entry, it got the label 1.1. (You’ll see why I used two digits later.) The figure below shows how I’ll represent the growing Zettelkasten. On the left is the conceptual tree (one node) and the contents of the card box (one card).

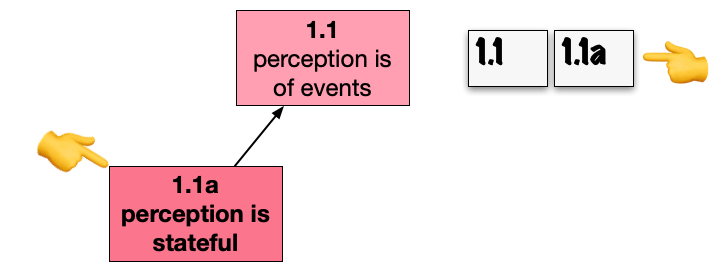

The saga of note 1.1a

As a longtime computer programmer, there are certain distinctions I’m attuned to. One is between systems that require memory and those that don’t. Early ideas of perception had all the memory in the Thinking part of the brain. Later people like Barrett have pushed memory into the perceptual system. Using my field’s jargon, the pre-Barrett model of perception was of a pure function, but now it requires mutable state.

That seems worth writing down, so I created a new card and called it “Perception is stateful” (using the jargon of my field – remember, I’m only writing this for myself).

Where should I put it? Since this observation was derived from 1.1, it makes sense for the new note to be “below” 1.1 in the tree structure. Since it depends on 1.1 in a historical sense, it should depend on that note in the “to hang down” sense, har har.

There’s also a sort of part-whole relationship between “We perceive events rather than snapshots” and “Perception is stateful.” Any feature of perception (like the importance of events) demands something of perception’s implementation (like state), and we usually think of implementation as lesser than (“below”) features. In general, humans think higher things are better than lower things. There’s a reason heaven is up and hell is down, or that “the highest praise” is the best kind. See Metaphors We Live By, George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, 2003 (2/e).

Whatever my reason, the new note gets label 1.1a:

The alternative would have been to make the new note a sibling. Let’s see an example of that.

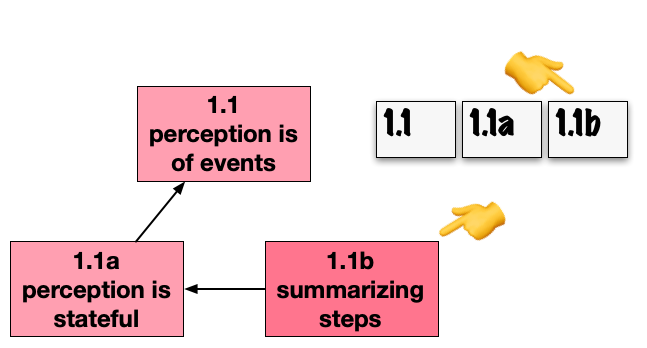

1.1b vies for attention

Barrett has more to say about the perceptual system that’s worth recording. For example: “Perception proceeds in summarizing steps.“ The visual system is a good example. Inputs from the neurons in your retina get special processing to detect lines, edges, and basic orientations. The output of such processing gets fed to other areas that make summaries like “what objects are there in the scene?” and “what’s in front and what’s in back?”.

Summarizing is part of the mechanism for distilling perceptions into events, so it seems it should be somewhere below 1.1. Perhaps below 1.1a? But it’s not really a part of 1.1a’s claim that perception is stateful. The new claim is related, but not dependent. So I choose to make it 1.1b:

The leftward arrow in the tree diagram reflects the relative positions of 1.1a and 1.1b in the imaginary card box. The arrows aren’t really needed, but I think they make the tree structure look nicer in this explanation.

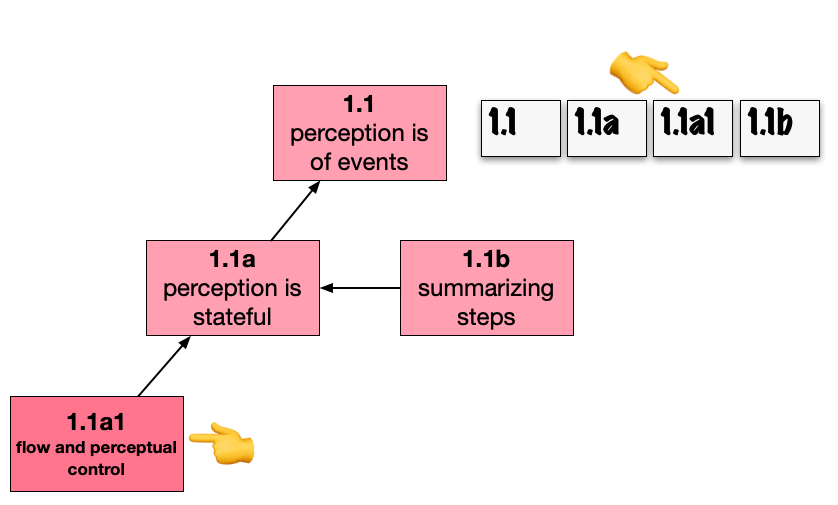

1.1a1 joins the chat

Consider someone “in the zone” on a programming project or video game, who keeps on even as their bladder or stomach (or wrists) are complaining bitterly. Not I would know anything about that, oh no indeed.

The brain has evidently decided that coding is more important than peeing. But does that mean the bladder is constantly sending “30% full,” “40% full,” “80% full” events that are being ignored? Some brain scientists think not. Instead, the brain implements “coding is more important than peeing” by telling the perceptual system (technically, the interoceptive system) to forward no bladder events until it’s at the “Dude, I’m way overfull and about to let go!!!” level.

The brain isn’t ignoring that the bladder is nearly full: it literally doesn’t notice.

So we have a perceptual setting that’s being tuned from outside the perceptual system. The new setting persists until changed. That means memory/state, again. Which suggests a new card below 1.1a – it elaborates on that card’s idea of state.

What to title it? Well, the brain’s adjustment only happens in certain contexts. The one that seems most relevant is what Mihali Csikszentmihalyi called “flow.“ “a state of concentration or complete absorption with the activity at hand and the situation. It is a state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter.” – Wikipedia

That seems like a nice card title: “Flow involves tuning of perceptual levels.” Here it is:

Browsing

The tree is now complicated enough that we can pretend to use it.

Suppose you’ve arrived at 1.1b, “Perception proceeds in summarizing steps,” for whatever reason. You don’t need an explicit link to know that its parent has label 1.1 and that there’s a sibling labeled 1.1a – the labeling scheme tells you that much.

You don’t know there’s a 1.1a1. But you can just flip to the card before 1.1b and look. The previous card will always be the last card in the 1.1a subtree (which might be 1.1a itself, but isn’t in this case).

Thus far, there aren’t more cards to the right of 1.1b. But if there were, you wouldn’t know if the first one was 1.1c or something else: perhaps 2.1. But all you have to do is flip the current card in the other direction and look.

In practice, when you arrive at a card in a new part of the Zettelkasten, you’re going to flip over its adjacent cards (in both directions), just to see if there’s anything interesting there. You’ll keep flipping as long as you keep being interested. Basically, you examine nearby subtrees until you get bored.

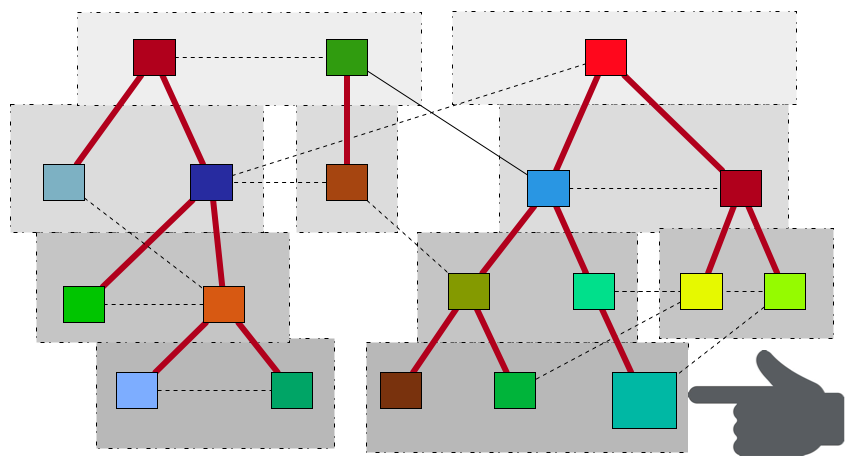

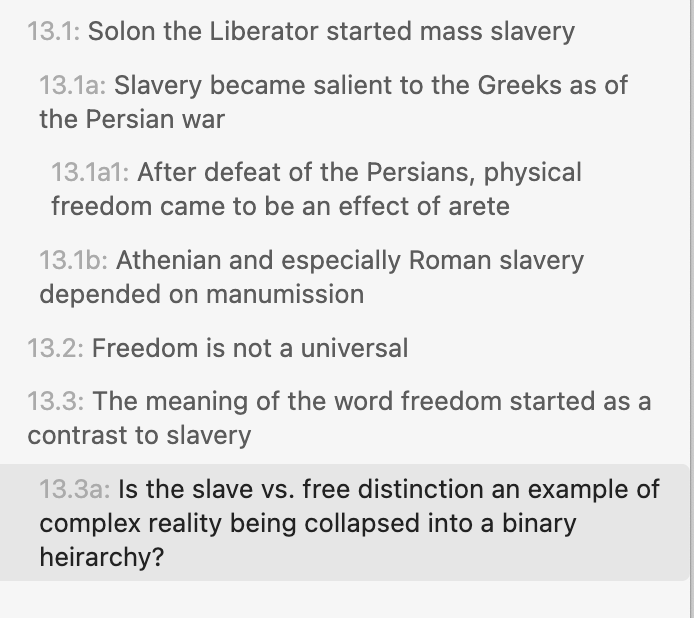

Electronic tooling makes that somewhat easier. For example, I took a few notes on a podcast episode that claimed that the concept of freedom evolved as a reaction to a new kind of widespread slavery. If I wanted to revisit that, I could ask my tool to show me the subtree:

… and I can examine the nearby notes by clicking instead of flipping.

1.2 butts in

At some point, I started making other notes about the brain, starting with “The brain is associative.“ “Associationism is a theory that connects learning to thought based on […] the organism’s causal history. […] In its most basic form, associationism has claimed that pairs of thoughts become associated based on the organism’s past experience.” – Stanford Dictionary of Philosophy. I’m an associationist, which is why I think new ideas come from “juxtaposing” (or making an association between) two or more older ideas. Where should that go?

Let’s imagine we’re using a physical card box.

The new card doesn’t belong to the subtree under 1.1, since those claims are all about perception. Still… perception is something the brain does, and I’m claiming “maintaining associations” is another thing the brain does. So it makes sense to name the new note 1.2, thus putting it “next to” 1.1.

For fun, I’ll flesh out the 1.2 subtree with some of my other notes, producing this structure:

Remember, you can click to enlarge.

Location markers

It looks like the 1.X series of notes have turned into “where I put a bunch of claims about the brain.” It’s easy to remember that fact, given that so far there’s nothing but 1.X cards, but (as I write) I’m already up to 18.X. So pretend my Zettelkasten is both physical and far more mature, and that the brain claims were actually found in 13.1, 13.1a, 13.2, and so on. It might be handy to mark where those brain cards start:

I’m not sure if Luhmann used such markers.

Note that the brain note is labeled 13. I can do that because I follow Bob Doto’s suggestion (in A System for Writing) of making the topmost nodes of the form N.n.

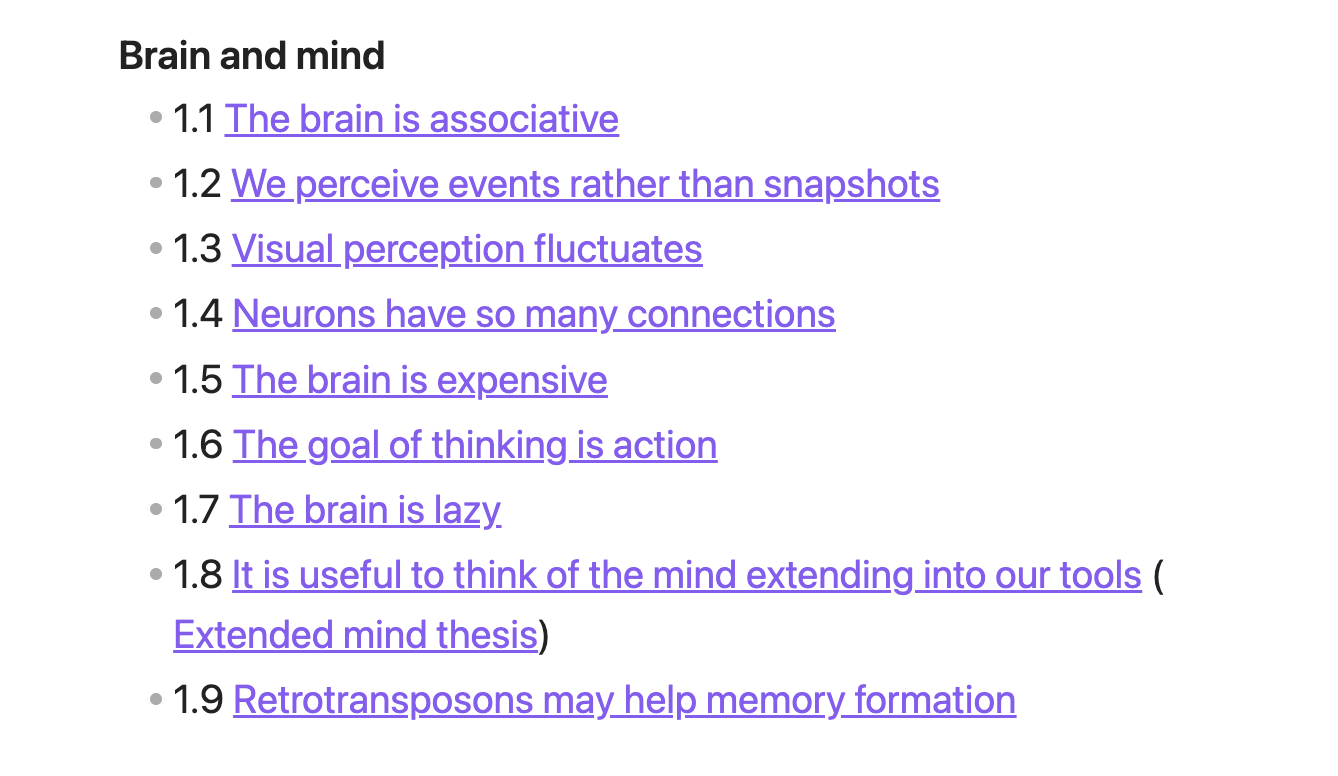

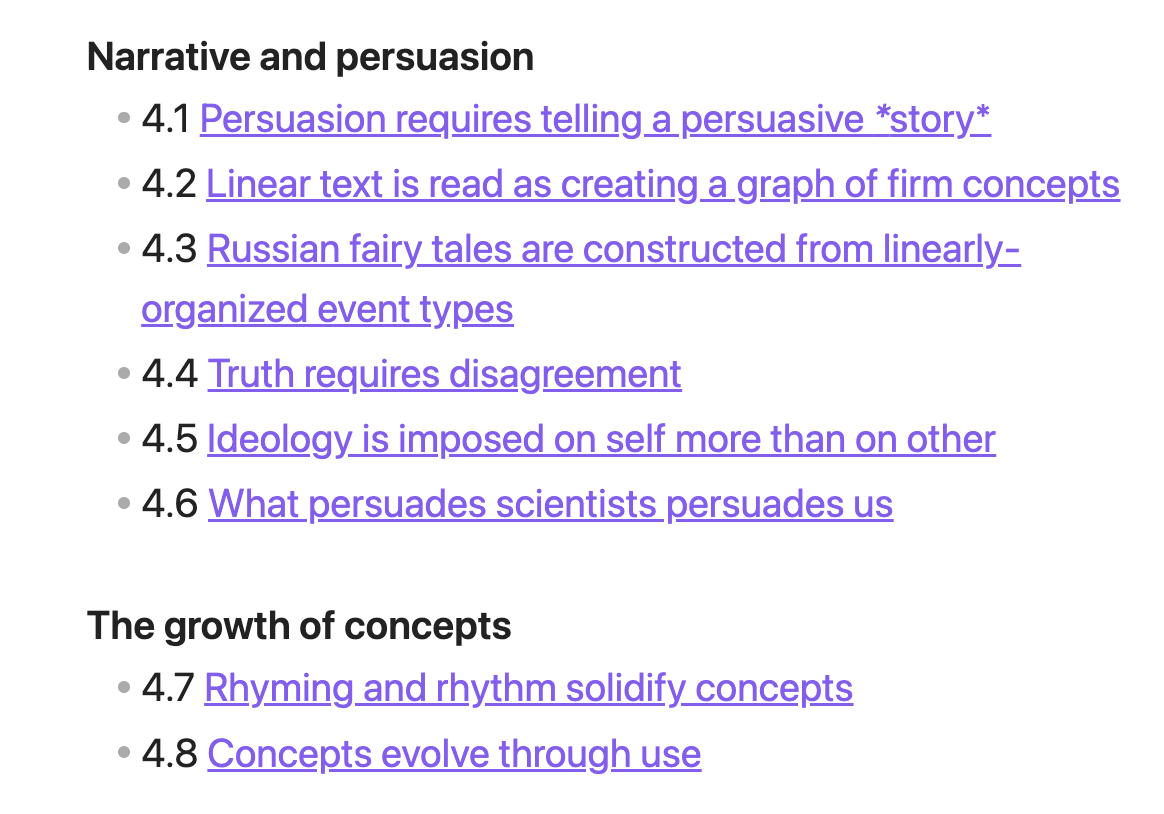

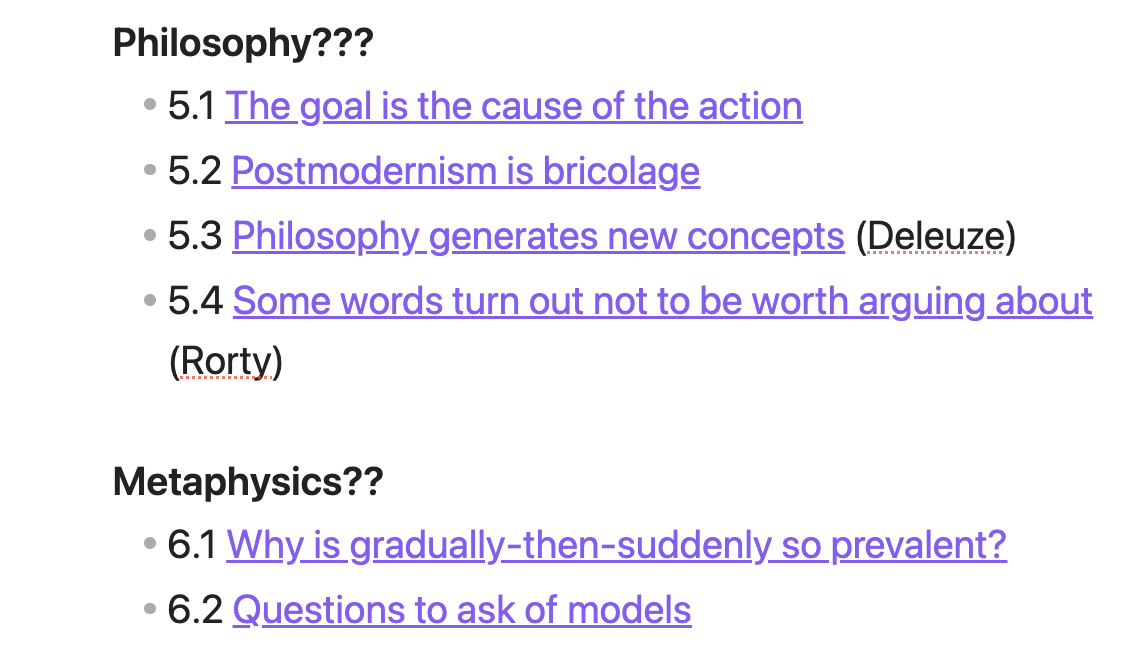

I do something similar, which is a full note or long page that provides a rough grouping of all the top-level notes. Here’s the beginning:

4.x root notes are divided into two chunks, each labeled with a vague-ish group name. You can also see that I’m unconvinced that there are easily-labeled themes to the 5.x or 6.x groups or even, really, that there’s a distinction between them.

That’s OK. I’m not trying to “carve nature at its joints.“ The term is from Plato’s Phaedrus. When dividing a carcass, it’s easier to use a cleaver at the joints than in the middle of the bone. Similarly, when dividing nature into categories, there are natural dividing lines. I join with others in thinking that idea (or the equivalent desire for categories to have clear in-or-out conditions) is attractive but bogus. See Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about the Mind by George Lakoff, or The Big Book of Concepts by Gregory Murphy. This list of top-level title-links is just a convenience I mostly use to search for where to put new notes. (There will be more about searching and browsing in the next major section.)

22.1 upsets the apple cart

I read Csikszentmihalyi’s Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience some decades ago, and I probably still have it around somewhere in the house. Suppose I decide to reread it and take notes this time. Suppose the first resulting card is titled “Flow is complete absorption in an experience.” I would add it to the graph as follows:

There’s a problem. I already mentioned “flow” in card 1.1a1. It now seems as if that card would better belong in the 22.1 hierarchy.

What do I do with it?

I do not move it. That’s not so much because putting a gap into the sequence of cards will be annoying and possibly confusing. It’s more because having a card disconnected from the “flow” tree is a benefit, not a problem. I’ll talk about that in the next major section. (Almost there!)

For the moment, I want to emphasize that adding a new card is not like adding a new species to a taxonomic tree. If you want to add a new species of trilobite to the fossil record, you know it will go within class Trilobita. It’s got big compound eyes, so it goes into the Phacopida (“lens face”) order. Its rather boring body places it in genus Flexicalymene. It’s different from the other known species of that genus, so you name it with a latinate version of your favorite childhood pet and call it a day. Don’t @ me, scholars of cladistics and the subtleties of biological classification. I know it’s not that simple. That it is, in fact, hard to impose a useful tree structure over an irredeemably messy world. Zettelkasten, in my interpretation, doesn’t much try. It embraces the mess.

Adding notes to a Zettelkasten is not trying to build a conceptual hierarchy.

Adding and using notes (creative version)

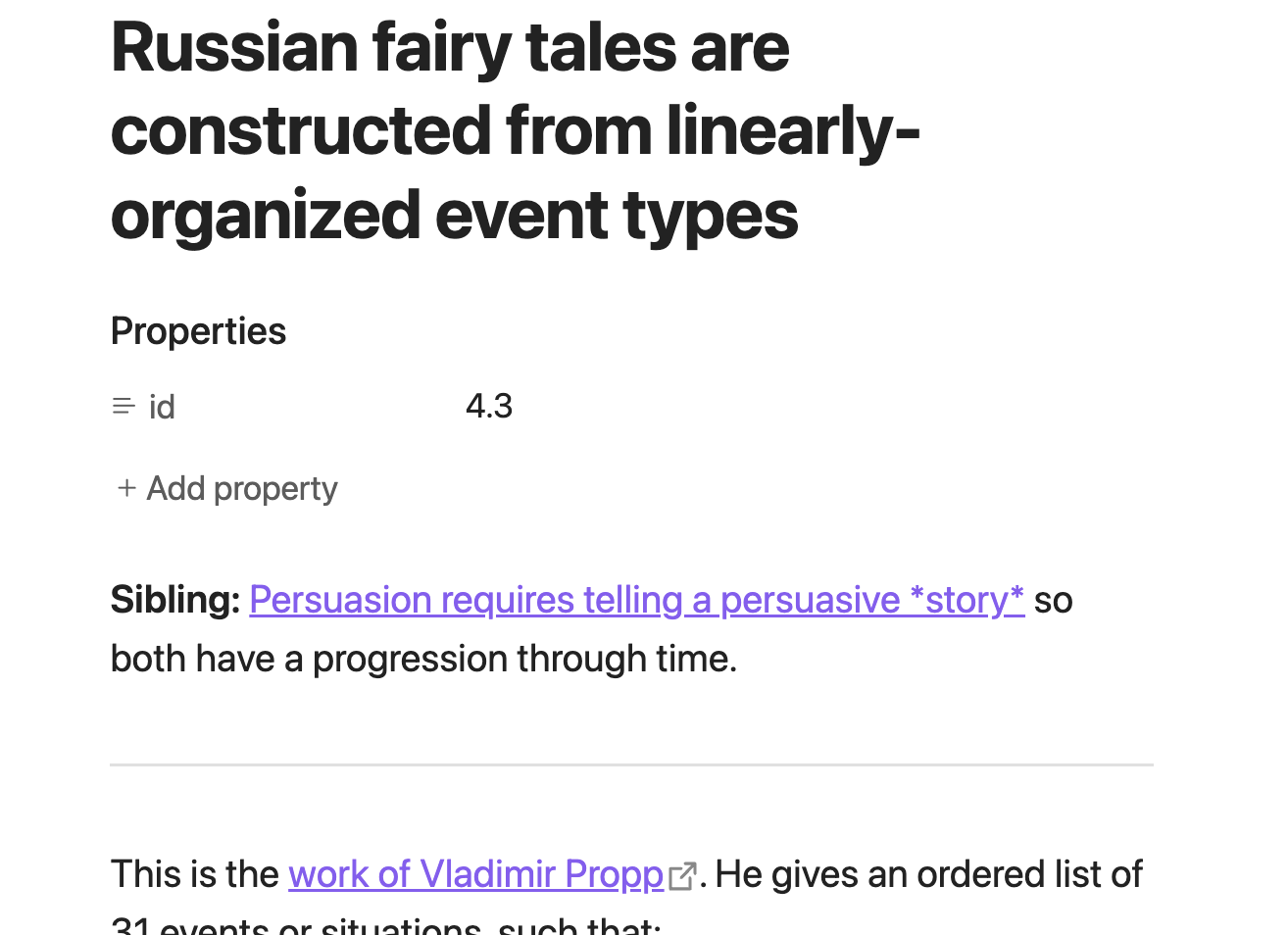

I’m interested in a particular intellectual approach called structuralism. People explaining it, especially in the context of literary criticism, will often use an example from Russian fairy tales. So it’s unsurprising my first note on the topic had the following text: I originally read this claim in Jonathan Culler, Structuralist Poetics: Structuralism, Linguistics and the Study of Literature, 2002.

Russian fairy tales are constructed from linearly-organized event types

This is the work of Vladimir Propp. [wikipedia link] He gives an ordered list of 31 events or situations, such that:

- In a story, event m must occur before any event later in the list of 31. (No backtracking.)

- Events may be skipped.

So the process of storytelling might be selecting a sequence of plot points – 2, 4, 5, 10, 18, 30 – which are then elaborated.

(This card is perhaps too wordy, containing facts I’d be unlikely to forget. That’s because I copied most of it from a draft podcast script about structuralism. I’m hoping extracting notes from the draft script will help me over the hump of turning it into a final script.)

The next step is to decide where to put it. I know structuralism is a new topic for my Zettelkasten, so it will likely be a top-level note. I could just give it an unused “major number” (19) and label the note 19.1. But that would leave it disconnected from other top level notes. Maybe I can find a top-level note that would make a good sibling?

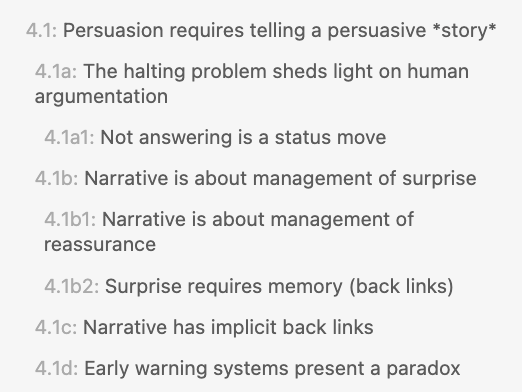

When I look through the list of top-level title-links, I see this:

- 4.1 Persuasion requires telling a persuasive story

- 4.2 Linear text is read as creating a graph of firm concepts

4.1 is intriguing. Clicking on the link shows this paragraph:

The claim here is that humans are built for listening to stories, so a persuasive narrative will have a “timelike” structure in addition to a logical structure.

Comparing that to “Russian fairy tales are constructed from linearly-organized event types,” I can see a loose connection: both are about a vague concept of “story,” and both are about sequences of events in time. So I’ll put my new note in the 4.x hierarchy. Since there’s already a 4.2, the new note will be labeled 4.3.

I could leave the link between the two implicit, but my habit is to document which sibling caused my decision, and perhaps why I thought I cared. (That latter is the same elaboration I might do for any title-link within a note.) So the top of the new note looks like this:

Click to enlarge.

Now that there’s a link from 4.3 to 4.1, there’s a question of whether it’s worth adding an explicit back link from 4.1 to 4.3. It’s not strictly necessary, since:

- If I’m doing serious work with any claim, I should scan its siblings, just as a normal practice.

- Obsidian makes it trivial to view the titles of all the notes that link to a given note.

So I only add explicit reverse title-links if it would be useful to expand on their text. In this case I chose not to. If I ever use the connection between the two, maybe I’ll change my mind.

But just adding a note isn’t the point

The act of adding a note would ideally prompt me to include relevant title-links in its text. Maybe there’s something useful to say about the (implicit) connection between the new 4.3 and the earlier 4.2? As it turns out, nothing came to mind after a brief scan of 4.2.

4.1. I found these two interesting:

Although these notes are directed to non-fiction narratives, it occurred to me that Propp’s model of fairy tales reads like a small child’s idea of a story: “and then this happened, and this happened, and then this other thing happened.” B-o-r-i-n-g.

If your only guide to writing Russian fairy tales was Propp’s model, you’d very likely write a bad one, because you’d be missing so much about what makes stories engaging.

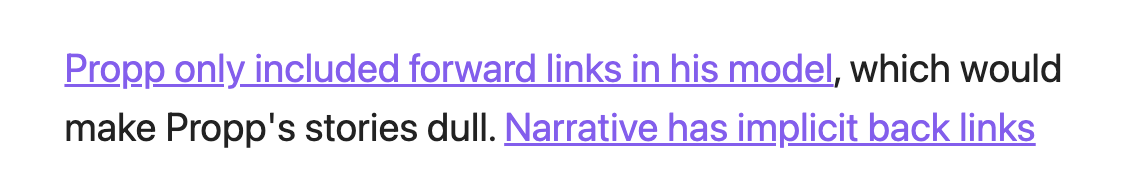

That seems worth noting, so I created a new note, “Propp only included forward links in his model,” with title-links to the 4.1b and 4.1c claims. That was a matter of less than a minute. The new note automatically appeared in my “to be processed later” Inbox, so I was finished with it for now. No stopping a task in the middle to go off and finish a subtask for me, no sir – that way lies madness.

In the software business, this is called “yak shaving.” The Mind Collection gives an example: “Imagine it’s your weekend and you sit at home trying to finish writing that important report for work. Your laptop battery dies so you need to fetch the charger from the office. You don’t have a key, though, so you call a colleague. He’s happy to help but he’s at his son’s basketball game. […] This is how you end up eating burgers and fries with a visibly proud dad and his son.”

I also decided to put a link to that new card on the original Propp note:

What I’d done made me think about structuralism more generally. I realized the other go-to introductory example of structuralism, Lévi-Strauss’s model of kinship, also has that feel of “as simple as possible and, in fact, maybe even simpler.“ “In every field of inquiry, it is true that all things should be made as simple as possible – but no simpler. (And for every problem that is muddled by over-complexity, a dozen are muddled by over-simplifying.)” – Sidney J. Harris

So I drafted a note titled “Structuralism tends toward minimalism” to elaborate on later. That’s more of a hypothesis than a solid claim. If I ever decide to use it in a proper narrative piece, I’ll do some more reading.

In sum, when writing notes, your goal should not just be to record the new claim, but to explore for a little while to see if somehow-related claims give you new ideas.

This production of new ideas is why I call Zettelkasten a “serendipity machine.” I’m thinking of “machine” in the sense of the basic machines of physics – the inclined plane, the pulley, and so on. They make tasks you could already do easier to do, and make possible tasks that would otherwise be beyond your abilities.

The task in question is being creative by bashing different ideas together. I’m already pretty good at making connections between disparate topics, but my Zettelkasten thus far seems to be making me better.

Other lists of title-links

It would be silly to be a stickler for a rule that every note must be a distinct claim. Early on, I felt the need to add summary notes, like this one:

Simmelian numbers

This is a collection of numbers and ranges that keep cropping up in sociology (at least according to Randall Collins).

When a source provides me a list of claims (like Ostrom’s nine principles for designing a commons) Ostrom’s career demolishes Hardin’s “Tragedy of the Commons.” Hardin is my go-to example of a theorist boldly asserting the flat impossibility of something people do all the time. But I digress. it would be silly not to copy it into the Zettelkasten.

These notes live in the same trees as those whose titles are claims. Ostrom’s note happens to have label 8.1, but it could also have been buried more deeply.

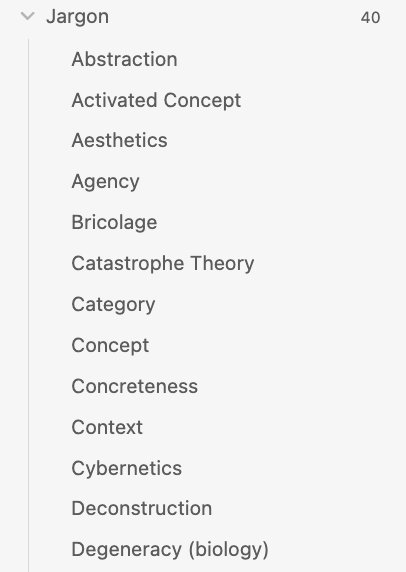

In addition to such notes, I also follow Luhmann in having a separate set of pointers from keywords to relevant notes. Here is a sampling of mine:

Note that it’s rather a hodge-podge. There are names of concepts or abstractions, like… Concept and Abstraction. There are whole technical fields, like Cybernetics. There’s technical jargon like Degeneracy (biology) or Bricolage. There’s even flat-out slang, like Grok (not shown).

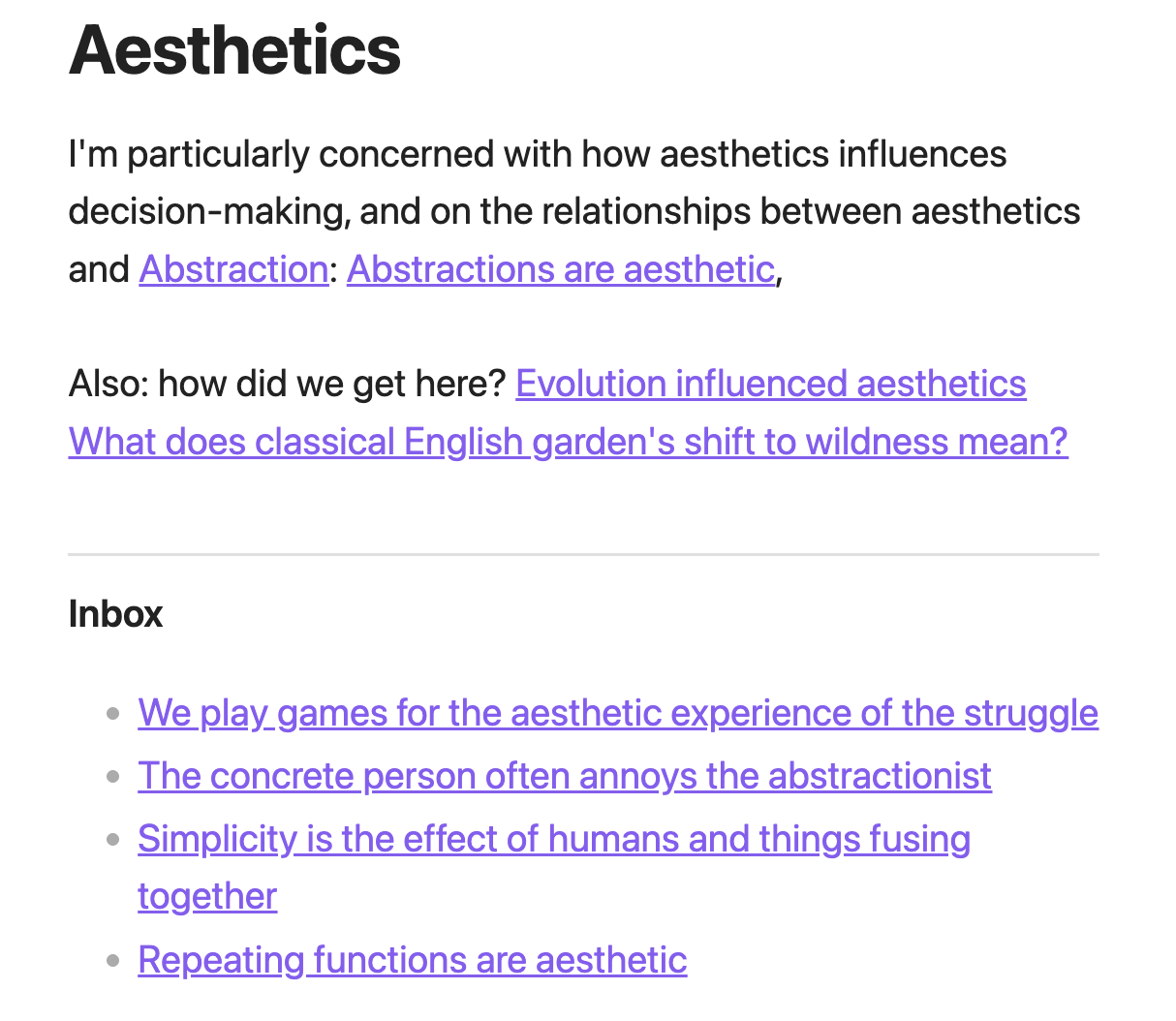

I label the entire collection of such notes “Jargon” because I don’t want to give the impression (to myself) that I’m somehow Capturing the Platonic Essence of, say, “Aesthetics.” A Jargon note is humbler: just some annotated title-links to notes that have some relevance to a word or phrase. Here’s the Aesthetics note:

When I create a new note, if I think it’s especially relevant to aesthetics (and if I remember I have a Jargon note with that title), I put an Aesthetics title-link on it. (This is like adding tags in many hypertext systems, including Obsidian.) That link automagically means a title-link to the note appears in the Inbox section of the Aesthetics note. At my leisure, and if it suits my fancy, I can pluck the title out of the Inbox and add a little context.

When searching for where to put a note (and finding some notes it should link to), I’ll occasionally use the Jargon notes in addition to my list of top-level title links. I also sometimes use full-text search.

I think what I’m calling Jargon notes have some important characteristics:

-

You create them when they’re convenient, not according to any fixed rule. If you want to get fancy, they emerge in the moment out of the complex interactions between a Zettelkasten and its human.

-

They strike a personal balance between discoverability and serendipity. You want to find particular notes easily, but not so easily that you don’t benefit from chance juxtapositions thrown up by your search. I expect the balance will depend a lot on the quirks of each person’s memory. (Mine seems to be worse than Luhmann’s was.)

My understanding is that Luhmann would sometimes browse his Zettelkasten with no fixed goal in mind. I can imagine such browsing as both throwing up juxtapositions but also maintaining his feel for the structure of his semi-structured mess. Memories are generally strengthened when they’re retrieved, so random browsing can avoid over-remembering frequently-accessed claims at the expense of forgetting the less-used ones.

Trails

A narrative, I said at the start of this post, starts as a linearized sequence of claims, possibly rearranged for purposes of narrative effectiveness. That actually echoes something from the very beginning of hypertext as a concept.

Vannevar Bush administered much of the government-funded research and development for the United States during World War II. He played a significant role in establishing postwar support for basic research. And he was the first popularizer of hypertext, in a 1945 popular magazine article. “As We May Think” The Atlantic Monthly, July 1945. One thing he emphasized there was associative trails, echoing in metal and optics what’s present in the brain:

The human mind […] operates by association. With one item in its grasp, it snaps instantly to the next that is suggested by the association of thoughts, in accordance with some intricate web of trails carried by the cells of the brain. It has other characteristics, of course; trails that are not frequently followed are prone to fade, items are not fully permanent, memory is transitory. Yet the speed of action, the intricacy of trails, the detail of mental pictures, is awe-inspiring beyond all else in nature.

He imagined users of his hypertext device, dubbed a “memex,” creating physical instantiations of mental trails:

The owner of the memex, let us say, is interested in the origin and properties of the bow and arrow. […] He has dozens of possibly pertinent books and articles in his memex. First he runs through an encyclopedia, finds an interesting but sketchy article, leaves it projected. Next, in a history, he finds another pertinent item, and ties the two together. […] Thus he builds a trail of his interest through the maze of materials available to him.

And people would purchase trails:

Wholly new forms of encyclopedias will appear, ready-made with a mesh of associative trails running through them, ready to be dropped into the memex and there amplified. […] The patent attorney has on call the millions of issued patents, with familiar trails to every point of his client’s interest. The physician, puzzled by its patient’s reactions, strikes the trail established in studying an earlier similar case, and runs rapidly through analogous case histories […]

There are trails in our modern hypertext documents, but they’re generally implicit. When reading Wikipedia, you can make your own trail, but there’s no tradition of making such trails permanent, something you could give to someone else. I think Bush vastly underestimated the importance of the “connective tissue” – narrative technique – that has to be added to a list of links to make it something people will read and benefit from. Writing this post would have been so much easier if I could have just dumped a list of claims onto you. Instead I spent a lot of time on the ordering and grouping of those claims, the tone of my exposition, and so on. That you’ve read this far suggests that was time well spent. Or that you’re made of more patient stuff than most.

But, since the purpose of a Zettelkasten is to support narratives – that is, trails of claims – its owner can make notes containing trails, notes that will be fleshed out into a proper narrative. (I can make a trail that’s meaningful to me much more easily than one that’s meaningful to some target audience.)

For example, I found it useful to preserve this trail:

… which I’ve titled “What’s the relationship of a Lakatos-style novel confirmation to narrative surprise?” Someday I can flesh that out into an essay or part of an essay. (I should probably add some text to the bare links before I forget what I had in mind.)

Note two things:

-

A trail is another list of title-links that provides a window into the full document.

-

Harvesting title-links for a trail will very likely provoke new claims because of the juxtaposition of old ones. Or it might suggest new topics to read up on.

A peculiar summary message

I took notes in exactly one class in college. (Abstract Algebra, I think.) I have since dabbled in note taking and note-taking tools off and on. Zettelkasten is the first one that seems at all likely to stick. Why?

A Zettelkasten document is “a mess with a non-arbitrary internal structure,” and I enjoy messing with that mess. It’s fun making linkages and especially fun when two notes spawn a new one.

Luhmann has a metaphor for that. He refers to the Zettelkasten as a communication partner. His “Kommunikation mit Zettelkästen,” linked above, is translated as “Communications with Zettelkastens.” In that paper, he speaks of “we”: “We (me and my Zettelkasten) obviously tend to think of systems theory […]” or “After 26 successful years with only occasionally difficult teamwork, we can report […]”.

Luhmann describes what’s needed for his Zettelkasten partner to keep holding his interest. The two words that stand out to me are “surprise” and “randomness”:

-

The Zettelkasten must be able to surprise by, metaphorically, advancing an unexpected claim. You don’t want a conversation where the Zettelkasten only ever repeats back to you what you told it last month.

-

Randomness is a mechanism that leads to surprise. It’s not that you don’t know what you’ll get when you ask the Zettelkasten about the claim on card

17.a3b8; it’s more that the Zettelkasten has the “yes, and” attitude. “A rule-of-thumb in improvisational comedy that suggests that an improviser should accept what another improviser has stated (‘yes’) and then expand on that line of thinking (‘and’)” – Wikipedia As you browse around (whether with a goal in mind or randomly), the mechanism should be such that you frequently think – at least glancingly – about the implications of two notes you’ve never looked at together (or haven’t for a long time, but your learning since then may interact with those past claims in new ways).

But that seems uncomfortably grandiose. Less imposingly, I think that for me, possibly for Luhmann, perhaps for other users of Zettelkasten, at least some of its appeal is that frobbing is fun.

Huh?

“To frob” is computer programmer jargon from the 1970s. As described in the Jargon File: “The original Jargon File was a collection of terms from technical cultures such as the MIT AI Lab […]” – wikipedia. A version edited by Guy Steele was published in 1983 as The Hacker’s Dictionary and was roughly this version. A later edition, The New Hacker’s Dictionary, seems to be widely considered by old-timers (including me) to have gone wildly astray.

Usage: frob, twiddle, and tweak sometimes connote points along a continuum. ‘Frob’ connotes aimless manipulation; twiddle connotes gross manipulation, often a coarse search for a proper setting; tweak connotes fine-tuning. If someone is turning a knob on an oscilloscope, then if he’s carefully adjusting it, he is probably tweaking it; if he is just turning it but looking at the screen, he is probably twiddling it; but if he’s just doing it because turning a knob is fun, he’s frobbing it.

Comments? As part of my move to resurrect the Republic of Letters, I’ve established an email address you can use to reach me. Include a first-line salutation to me, “Brian Marick” (honorific optional), and I will reply as soon as the packet boat brings your missive to me.