Hypertext documents vary a good deal, so statements beginning “Hypertext is…” are likely to obscure more than they reveal. In three posts, I’ll discuss the dominant style (“wiki traditional”), one that flips the emphasis (“Zettelkasten”), and how well two metaphors (“garden” and “rhizome”) work for each. My premise is that if you understand what you’re doing when you write a particular kind of hypertext, you’ll do it better.

An exemplar

The book contains 253 numbered texts (called “patterns”) to be used by people constructing towns and buildings. The texts are usually several printed pages long. Each text has a numbered title, ranging from “1. INDEPENDENT REGIONS” to “253. THINGS FROM YOUR LIFE.” Because the book is a paper document, a text links to another text by mentioning its title. Here’s an example of a sentence containing two links:

Titles, such as those at the head of a pattern’s text, have the numbers first, whereas link text puts the numbers last. The numbers-first style makes scanning for a matching number easier, and the numbers-last reads better in blocks of text with multiple links.

The maximum is a cottage – like a

TEENAGER'S COTTAGE (154), or anOLD AGE COTTAGE (155)[…]

141. A ROOM OF ONE'S OWN,” which means that 154 is not much deeper in the book. So you flip over a hunk of pages, look at the top of the page you’re now at, which reads “158. OPEN STAIRS,” then page back a bit until you get to 154.

The most common title is a noun phrase like the ones above. Some are more abstract, like “190. CEILING HEIGHT VARIETY,” but they’re still “noun focused.” Even ones like “208. GRADUAL STIFFENING” or “63. DANCING IN THE STREET” use gerunds: that is, verbs acting as nouns. There are exceptions, like “40. OLD PEOPLE EVERYWHERE” and “205. STRUCTURE FOLLOWS SOCIAL SPACES,” but they’re scarce. Overall, the titles refer to places (more generally: “things”) and the texts talk about how to create such things.

The overall structure is what I’ll call “roughly hierarchical with two way links.” The idea is that you, the reader, want to learn how to construct something. Let’s suppose you’re a city planner who’s been given the job of reconstructing an unhappy neighborhood to make it better for the people (a “subculture”) who live there. You’ve read 31. PROMENADE, whose summary reads:

Each subculture needs a center for its public life: a place where you can go to see people, and to be seen. (emphasis in the original)

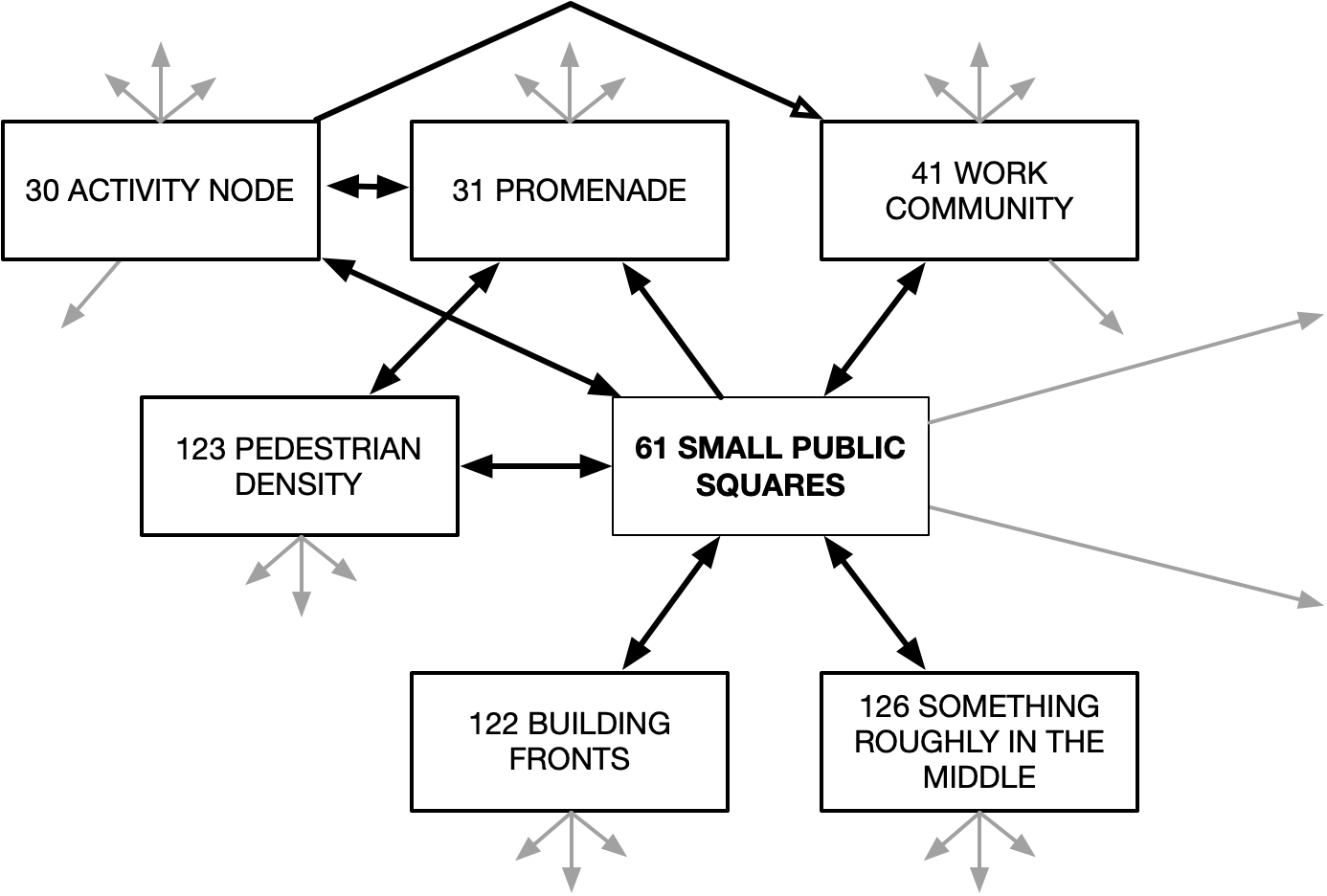

That seems a useful place to have, but how do you design it? When I went to Bologna many years ago, it was rather charming to watch little old people promenading around a public square just outside my hotel. So maybe you want one of those. To learn about it, you can follow a link to 61. SMALL PUBLIC SQUARES.

There actually isn’t a direct link from 31. PROMENADE to 61. SMALL PUBLIC SQUARES – you get there indirectly via 30. ACTIVITY NODE – but let’s ignore that. I suspect omitting the direct link was a mistake. It’s hard to keep track of backlinks manually.

61. SMALL PUBLIC SQUARES has a discussion of what makes public squares work. After that, there are suggestions for possible (or mandatory) constituent parts:

[…] build buildings around the square in such a way that they give it a definite shape […]

BUILDING FRONTS (122),STAIR SEATS (125); and to make the center of the square as useful as the edges, buildSOMETHING ROUGHLY IN THE MIDDLE (126)…

126. SOMETHING ROUGHLY IN THE MIDDLE recommends that the something have a SITTING WALL (243).

So the structure around 61. SMALL PUBLIC SQUARES looks like this:

All images can be clicked to see a larger version in a new tab.

As p. xii puts it:

Each pattern is connected to certain “larger” patterns which come above it in the language; and to certain “smaller” patterns which come below it in the language. The pattern helps complete those larger patterns which are “above” it, and is itself completed by those smaller patterns that are “below” it.

Notice that the things described can be abstract (an “activity node”) or concrete (a wall to sit on).

Generally, if a text links to another text, that other text will link back. For example, 125. STAIR SEATS (linked to from 61. SMALL PUBLIC SQUARES) begins:

… we know that paths and larger public gathering places need a definite shape and a degree of enclosure, with people looking into them, not out of them –

SMALL PUBLIC SQUARES (61),POSITIVE OUTDOOR SPACE (106),PATH SHAPE (121). Stairs around the edge do it just perfectly; and they also help embellishFAMILY OF ENTRANCES (102),MAIN ENTRANCES (110), andOPEN STAIRS (158).

There can also be side links between two parts at the same “level” whose designs influence each other. For example, 65. BIRTH PLACES points sideways to HALF-HIDDEN GARDEN (111) and GARDEN WALL (95). You can can think of these links as saying: “If you choose to include a birth place, the mother’s desire for privacy when strolling with the child increases the desirability of a half-hidden garden or garden wall.” Side links emphasize the importance of iterating the mutual design of places when they’re at approximately the same level of scale.

That covers the parts out of which a particular hypertext document was built. But what of the end result? The introduction describes the individual patterns and the whole assemblage with words like “whole”, “coherent,” “alive,” “the core of the solution,” “clarity,” “complete,” “the heart of all possible solutions,” “essential,” “invariant property,” “properly,” “deep and inescapable,” “well-formed,” “true,” “profound,” “totality,” “human,” “natural,” “joyful,” “archetypal,” and “deeply rooted in the nature of things.”

That is, A Pattern Language fits into two long-standing intellectual/emotional worldviews: Platonism and structuralism.

Platonic idealism

Plato’s Theory of Forms holds that there are two “worlds.” One is the one we perceive, which is incomprehensibly complex. The other contains “Forms” or “Ideas” that cannot be perceived but only understood rationally. They are timeless, unchangeable, absolute, non-physical – choose your adjective – essences that are “behind” the world we see. For example, there are many triangles, but they are all reflections or emanations of a single, eternal and perfect Triangle. Emotionally, the Triangle is more real than any individual triangle.

Mathematics is the rational study of some of those Forms. As Davis and Hersh put it in The Mathematical Experience, as of 1981 the official word on mathematics, post-Hilbert, was that mathematics is formalist. That is, math is the study of the results of transforming sequences of symbols using a set of rules, without regard to what the symbols represent. “[Mathematics is] not a body of propositions representing an abstract sector of reality, but is much more akin to a game, bringing with it no more commitment to an ontology of objects or properties than ludo or chess.” – Alan Weir, 2014 However, they also say that working mathematicians are nevertheless secret Platonists: a commutative semigroup is a real thing, somewhere “out there.”

Alexander’s rhetoric of “the core,” “the heart,” “archetypal,” and “deeply rooted” is straight-up platonism. 61. SMALL PUBLIC SQUARE is a real thing that can be implemented or instantiated well or poorly (and any individual public square has no effect on the reality and unity and properties of the Ideal PUBLIC SQUARE).

This platonism is true both of individual patterns and the entire document. After all, the companion book is called The Timeless Way of Building. (My emphasis).

Structuralism

Structuralism is a methodology for inquiring about and describing human thought that seems so natural to STEM people like myself that it’s weird to think there could be any other way to do those things. Nevertheless, it only became thought of (in the West) as a distinct school of thought in the early-to-mid 20th century.

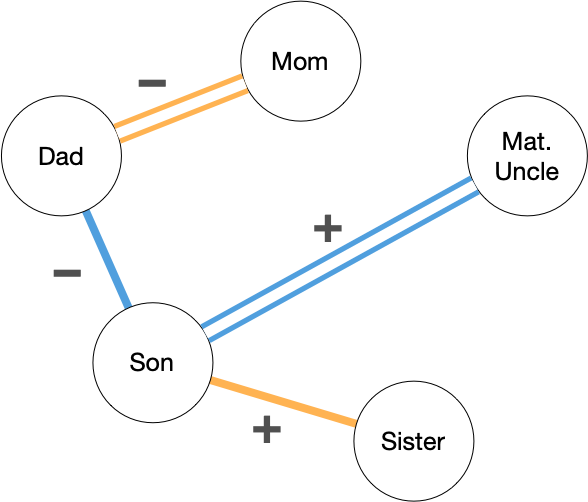

Broadly, you might be a structuralist if you thrill to diagrams like the following:

That’s my redrawing of anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss’s analysis of kinship relationships in female-donating societies. These are societies where marriage is formed when one man gives his sister or daughter to another man. I won’t explain the diagram except to say that he discovered that if a relationship between a particular pair of family members is “warm,” a different relationship must be “cold.” In the image, because mom and dad have a cold relationship, brother and sister must have a warm one.

In Lévi-Strauss’s Structural Anthropology, he credits the linguist Nikolai Trubetzkoy with writing down structuralism’s four basic principles or “moves.“ Structuralism originated in linguistics and then spread to other fields like literature, anthropology, and even mathematics (via the Bourbaki collective). My paraphrase follows, with what I want to emphasize in bold.

-

Conscious behavior (such as producing sentences) is supported by (or driven by) unconscious structures. More important than actually studying a language’s grammar is studying the underlying structures that control which grammatical rules you absolutely will find in a language, which rules might be found, and which definitely won’t be found.

-

What matters is relationships between entities, not properties of the entities themselves. The father’s character doesn’t matter in Lévi-Strauss’s theory of kinship; what matters is his relationship to his wife and his son.

-

The purpose of the work is to tease out the underlying structure. That’s a little circular: “structuralism is about structure.” So I’ll say what it means is that you should describe all the relevant relationships and how the relationships relate to each other. In the case of Lévi-Strauss, that means discovering rules like “mom-dad relationship must be the opposite of brother-sister.”

-

A structuralist theory must explain multiple real-world examples. Trobriand culture is matrilineal, and Tonga culture is patrilineal; Lévi-Strauss’s kinship diagrams work for both.

Reading backwards from (4) to (2), I argue that A Pattern Language is a product of a structuralist investigation. A large number of examples were boiled down to a set of 253 rules (or patterns) that could be used to create a variety of new examples that would exhibit properties of liveness, completeness, etc. That covers points (4) and (3).

(2) is not as strong. The entities are texts with titles like 180. WINDOW PLACE or 98. CIRCULATION REALMS, and most of the words in the text are used to explain what the title means and how to achieve it. That’s a focus on entities, not on relationships.

However, the links are given some weight, especially because they’re typed. That is, the reader is informed (or can easily infer) what she’ll get if she follows one. For example, you know that links at the beginning of a pattern point upward from a part to larger wholes. Downward and sideways links are generally found at the end of the pattern. And the words surrounding a link describe why the reader might want to follow it. Here, for example, is the end of 116. CASCADE OF ROOFS:

Make the roofs a combination of steeply pitched or domed, and flat shapes –

SHELTERING ROOF (117),ROOF GARDEN (118). Prepare to place large rooms in the middle –CEILING HEIGHT VARIETY (190). Later, once the plan of the building is more exactly defined, you can lay out the roofs exactly to fit the cascade to individual rooms; and at that stage the cascade will begin to have a structural effect of great importance –STRUCTURE FOLLOWS SOCIAL SPACES (205),ROOF LAYOUT (209)….

These words hint at the relationships between places (or entities), so I’ll say A Pattern Language exhibits structuralism.

Influence

The original wiki was created by Ward Cunningham, someone quite familiar with A Pattern Language, and it had many of the same properties (such as a preference for noun-phrase titles).

That wiki in turn influenced later wikis like Wikipedia. Here are similarities and differences between Wikipedia and A Pattern Language:

Wikipedia is also about things. Here are three random Wikipedia pages:

-

Saltash with the Water Ferry (a landscape painting)

-

Ridazolol, a drug.

From the Saltash page, you can follow the following inline links: landscape painting, Joseph Mallord William Turner, a bunch of links to descriptions of places like the English Channel and Devon, a English political category (county town), the concept seaside resort, and so on.

Noun phrases all over the place.

Wikipedia also mixes levels of abstraction. The first sentence of the Peter Coleman entry reads “Peter J. Coleman is an American competitive sailor.” Coleman is a concrete example of a general (platonic) category.

Pages also strive for completeness. There’s not a second Wikipedia page titled “More facts about Peter Coleman,” any more than A Pattern Language has a 117. MORE STUFF ABOUT ALCOVES.

The entire document pushes toward completeness. That’s inherent to the whole idea of an encyclopedia. The original encyclopedia, the Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, par une Société de Gens de lettres was “a collaborative collection of all the known branches of the arts and sciences of the 18th century French Enlightenment” (my emphasis). Its goal was “to create a method of systematizing and organizing all legitimate information and knowledge as well as make easier and more efficient the unearthing of more knowledge.”

Links are similarly typed in the sense that a reader will know what’s coming when she clicks on a link. As with A Pattern Language, it’s the surrounding words that gives the clue. For example, the link from Peter Coleman to competitive sailor is an is-a link. The next three links are equally predictable: “Peter and his brothers Paul Coleman and Gerard grew up in Larchmont, New York close to Horseshoe Harbour…”

Wikipedia is more completist than platonic. I’m not sure you can avoid platonism when you’re defining a noun phrase, but it’s notable that Wikipedia authors are happy to include information that Plato would in no way consider part of the essence or Ideal Form of, say, the German Shepherd. Such as this:

The Orthopedic Foundation for Animals found that 19.1% of German Shepherds are affected by hip dysplasia.

Is hip dysplasia part of the essence of Shepherd-dom? (Platonism has a lot of trouble with properties that are not either/or, true/false.)

Wikipedia is only shallowly structuralist. Structuralism favors minimalism (as does Platonism): it’s not enough to describe entities and their relationships; ideally, you want a minimal set.

In contrast, I very much believe that the Wikipedia style of writing hypertext (the one I use myself in my own wikis) consists of writing a sentence without caring about hypertext, and then saying to yourself “Ooh, I should change these few words into a link.”

The difference?

A Pattern Language and Wikipedia are pretty similar, but I think a reason for their differences is important:

Wikipedia is truth-presenting, whereas A Pattern Language is goal-directed.

A Pattern Language expects its audience to want to design.

The main reason I’m so fond of A Pattern Language is that, once upon a time when Dawn was out of town, I used it to redesign our front room, using patterns like Window Place and Circulation Realms and Light on Two Sides. And it worked! (How often can you say that about something you read in a book?) By “work,” I mean that a space that both family and guests at parties avoided became a place people gravitated to. It’s going on three decades, and I still spend hours every day in my Window Place.As a result, many of the its links are obligatory – if you want to build something, you have to follow links from wholes to parts (and, sometimes, parts to adjacent parts), all the way down to 240. HALF INCH TRIM and 246. CLIMBING PLANTS.

Next: Zettelkasten

Comments? As part of my move to resurrect the Republic of Letters, I’ve established an email address you can use to reach me. Include a first-line salutation to me, “Brian Marick” (honorific optional), and I will reply as soon as the packet boat brings your missive to me.