In his Illiberal Education, D’Souza uses numbers and statistics, um, liberally but not informatively. In this post, I’ll mix up discussing how he misleads and how you might recognize what he’s doing without having to look at his sources.

As with all these posts, I link to archive.org’s copy of Illiberal Education so that you can check my citations. Throughout, boldface indicates my emphasis.

Numbers are for comparing

D’Souza sometimes uses numbers to establish a vibe: a feeling that he’s bathing you in a sea of facts. But data has to be readily comparable to be useful to a reader. Consider his first chapter, on affirmative action, especially at Berkeley. Here are some numbers he gives in that chapter, describing a period of considerable policy fluctuation around enrollment: Ask my wife about time series data!

- Asians “now” make up 10% of California’s population (p. 27).

- In 1988, Asians were 26.2% of the Berkeley student population (ibid).

- In 1986, the number of “affirmative action acceptances” rose to 728 (ibid).

- “In 1987-88, Berkeley announced that it had achieved multiracial ‘parity’: black and Hispanic students were now equal to their share in the general population” (ibid).

- In 1989, the number of admissions for whites “dropped sharply to just one-third of the freshman class” (p. 29).

Quick questions: what percent of the California population were Black, compared to Asian, in 1990? What are the percentages for the freshman class? In the student population as a whole?

1991 was a primitive time, but the technology to typeset tables, and even line graphs, had been mastered. Critically assessing D’Souza’s data is absurdly hard, and his audience for the most part will just accept his conclusions, not interrogate them. In the words of Andrew Lang (attributed), “He uses statistics as a drunken man uses lamp-posts – for support rather than for illumination.”

Categorical variables

D’Souza’s first barrage of numbers begins on page 3. The very first statistic in the book is:

“At the University of California at Berkeley, black and Hispanic student applicants are up to twenty times (or 2,000 percent) more likely to be accepted for admission than Asian American applicants who have the same academic qualifications.” (p. 3)

When looking at a pile of disconnected statistics, it’s useful to tease out an underlying statistical model. For D’Souza, the model predicting the chance of a student to be admitted would look something like this:

cbasmAA(ethnicity, academic potential, school applied to) + unaccounted-for variation

// Read cbasmAA as chance of being admitted scaled to that of the mean Asian American)

Further scanning down page 3 will show the same input variables applied to a number of different output variables. For example, here’s a slightly different output variable, something like lowest scores of accepted freshman:

“several of these [Ivy League] schools admit black, Hispanic, and American Indian students with grade averages In secondary (pre-college) education, a US student will take some tens of classes over a period of four years. Each provides a final numerical summary of the student’s performance. The average of all the scores is the grade average (more often called grade point average or GPA). Most often, it’s scaled to lie between one and four. as low at 2.5 and SAT aggregates The SAT (Scholastic Aptitude Test} is a one-sitting summary test of performance in two categories, “Reading and Writing” and “Math.” Both are measured on an 800 point scale. Because two numbers are hard to keep in your head, I guess, people usually report the sum of the numbers, what D’Souza here calls the aggregate. ‘in the 700 to 800 range.'” (ibid.)

And here’s a final datum:

“In 1988, for example, the average white freshman at the university [of Virginia] scored 240 points higher on the SAT than the average black freshman.” (ibid.)

Here are things that jump out at me:

The first claim uses “black and Hispanic”; the second uses “black, Hispanic, and American Indian”; the third uses “black.” The ahem rebuttable presumption is that what D’Souza really cares about are Black students, not Hispanics or Native Americans, and that he scoured data sets for facts about any group containing Blacks for damning numbers about Blacks. Further evidence D’Souza isn’t concerned with Hispanics: The word “black” or “blacks” appears 1042 times, “Hispanic” or “Hispanics” 119 times, and “American Indian” or its plural 22 times. The vast number of times “Hispanic” occurs, it’s in phrases like “black and Hispanic students.” Only about 20 uses of the word “Hispanic” are actually about Hispanics (by my not-incredibly-rigorous scan of a long list of search results). D’Souza’s prime case study is University of California, Berkeley. In 1987, California’s population was 7.7% Black and somewhere toward the upper edge of the range 19.2% (1980) to 25.8% (1990) Hispanic. So, when D’Souza reported that, in 1987, “black and Hispanic students [at Berkeley] were now equal to their share in the general population” (p. 28), then talks almost exclusively about Black students, that increases my suspicion that D’Souza’s true topic is Blacks on campus rather than affirmative action in general.

Whenever you see a categorical variable like “ethnicity,” it’s useful to ask “how else could this population be sliced up into categories?” One sub-question is: “which people have been lumped together who might better have been split apart?” In addition to Black and Hispanic, the catch-all category of “Asian” caught my attention. There are lots of kinds of Asians! Are East Asians (China and so on) really so culturally similar to South Asians (Indian subcontinent)?

But more interesting – because harder to notice – is how D’Souza doesn’t consider alternate ways of dividing up students, such as “legacy” students vs. students who didn’t have a parent who attended the same university. Here’s a simple table (source) that shows the advantage or disadvantage of being in a category, expressed as an adjustment to SAT composite scores:

| Category | SAT adjustment |

|---|---|

| African Americans | +230 |

| Hispanics | +185 |

| Asians | -50 |

| Recruited athletes | +200 |

| Legacies (children of alumni) | +160 |

If I am interpreting this table correctly (I didn’t bother breaking the paywall to get at the original paper), a White legacy student with an SAT score of 1200 would be treated as if he were a White non-legacy student with a score of 1360. An African American legacy would get a double boost of 160 + 230. However, there are not many such people: “in practice, widespread legacy preferences have reduced acceptance rates for black, Latino, and Asian-American applicants because the overwhelming majority of legacy students are white.” – same source

Not only does D’Souza not explore alternate categorizations, he doesn’t even provide enough data to allow analysis of the categories he does provide: if he made a table, it would be mostly blank entries.

The missing half

Another way of slicing the data would be by socioeconomic status: rich vs. poor. D’Souza makes much (correctly, to my mind) of minority drop-out rates. He writes:

“Whites and Asians graduate from Berkeley at about the same rate: 65-75 percent. That is to say that 25-35 percent drop out before graduation. Hispanics graduate at under 50 percent. More than half drop out. Blacks graduate at under 40 percent. More than 60 percent drop out.” (p. 39)

I prefer a table: I think it was only when I made the table that I was struck by the difference between “65-75” and “under 50/40 percent.” That’s the kind of thing tables are good for. Curious, I checked D’Souza’s endnote. He cites two sources: “The Office of Student Research, UC-Berkeley,” and “James Gibney, ‘The Berkeley Squeeze,’ New Republic, April 11, 1988.” My guess is the range is from Berkeley and the other two are from the article. Which is weird. Did the Office of Student Research give D’Souza data for Whites and Asians but refuse it for Blacks and Hispanics? Did Gibney not report on Whites? Or, as D’Souza’s earlier shenanigans with citations allow us to suspect, did D’Souza ignore half of each source’s data to make the differences more stark? Alas, the Berkeley reference is impossibly vague, and the New Republic archives don’t seem to go back that far, so I’m stymied.

| Ethnic category | Graduation rate |

|---|---|

| Whites | 65-75% |

| Asians | 65-75% |

| Hispanics | “under 50 percent” |

| Blacks | “under 40 percent” |

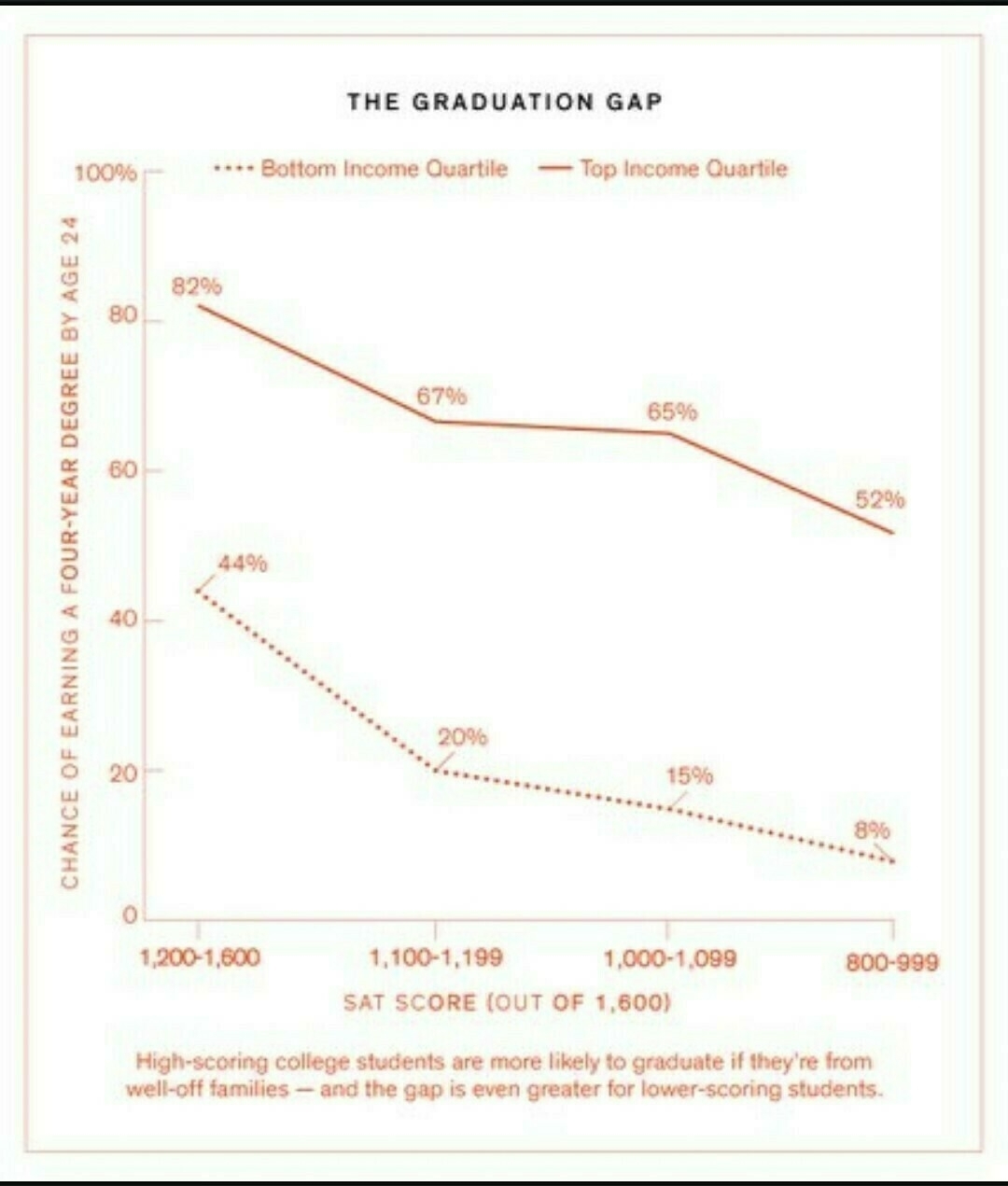

This table, though, doesn’t distinguish graduation rate by “academic potential” (D’Souza’s other favorite input variable). For that, you really need a figure. Here’s one that shows the effect of both socioeconomic status and academic potential (using SAT scores as a proxy): Source: “Who Gets to Graduate?” The New York Times Magazine, May 8, 2014. Found via Mastodon user Sheebalba.

Click to enlarge.

As expected, all things being equal, the higher the SAT score, the greater the chance to graduate. (That is, the SAT is an OK proxy for the unmeasurable variable “academic potential.") But being a student in the bottom (vs. top) quartile of parental income reduces one’s chance of graduating by 38 to 50% (depending on SAT score)! That’s very comparable to – most often worse than – the effect of ethnicity. I’m going to assume the “under 40 percent” graduation rate for Blacks doesn’t mean way under 40%, so the drop due to their ethnicity is at most something like 75-35 = 40%. Compare to the 38-50% effect of parental income.

This chart is especially relevant because, in his last chapter, D’Souza proposes scrapping the use of race in affirmative action and using socioeconomic data instead:

“[I]n admissions decisions, universities would take into account such factors as the applicant’s family background, financial condition, and primary and secondary school environment, giving preference to disadvantaged students as long as it is clear that these students can be reasonably expected to meet the academic challenges of the selective college. Race or ethnicity, however, would cease to count either for or against any applicant. […] Preferential treatment is justified, however, when it is obvious that measurable indices of merit do not accurately reflect a student’s learning and growth potential.” (p. 251)

He says this would “likely” increase graduation rates:

“Moreover, black and Hispanic graduation rates are likely to increase, because only students whose potential is hidden due to previous disadvantage would enjoy preferential treatment, in the reasonable expectation that they will be able to realize their capabilities and compete effectively with other students.” (pp. 252-253)

You saw a chart casting that conclusion in doubt. That chart was made in 2014, so D’Souza couldn’t have seen it (though he might have seen similar data). What’s galling, though, is he offers no data in support of his plan, just his opinions. Which prompts me to offer a heuristic:

If an author overwhelms you with numbers about why someone else’s idea (affirmative action that weights ethnicity) is bad, but gives no numbers about why his idea (affirmative action that weights by income and wealth) is better, distrust his motives.

Everything’s easy if you’re not the one doing it

“Ordinarily it might seem an extraordinarily complex calculus to weigh such factors as family background, income, and school atmosphere. Fortunately, colleges already have access to, and in many cases use, this data. The application forms give applicants ample opportunity to register this information, and the financial aid office assiduously tabulates family assets and income. By integrating admissions and financial aid information, universities are in a good position to make intelligent determinations about socioeconomic factors that advanced, or impeded, a student’s opportunities.” (p. 252)

However, universities are gathering that data to determine ability to pay for college in support of decisions about financial aid. D’Souza is blithely assuming that it’s easy to transform that data to get a good enough estimate for the unobservable variable “learning and growth potential.”

Does he make an argument for why that’s easy? No.

D’Souza could propose a trial program. If universities are already gathering the data, they could produce two admissions scores:

def admit_old(ethnicity, x, y, z) : Boolean ...

def admit_new(financial_aid_data, x, y, z) : Boolean ...

For all the students admitted under admit_old, they could also calculate admit_new. Now we have two groups of admitted students:

- Those that

admit_newwould have admitted - Those that

admit_newwould have rejected

How do their graduation rates compare? What does that tell us about admit_new vs. admit_old?

Doubtless there’s some better design to squeeze information out of the cheaply-available data. I know enough about data analysis to know I don’t know enough about data analysis.

D’Souza doesn’t propose any sort of investigation or incremental, feedback-driven approach – just a wholesale scrapping of any use of data on ethnicity. Nor is he clear on what outcomes should be measured. (Graduation rates wouldn’t be the only result of interest.)

I believe that D’Souza, like so many authors who like to sprinkle numbers into their arguments, doesn’t actually appreciate data as a way to come closer to understanding. Data is a tool for argumentation. Actual decisions are made by reasoning from axioms. D’Souza says:

“The greatest virtue of preferences based on socioeconomic factors is that such an approach restores to the admissions process the principle of treating people as individuals and not simply as members of ethnic groups. Each applicant is assessed as a person, whose achievements are measured in the context of individual circumstances. Skin color no longer makes a dubious claim to be an index of merit, or an automatic justification for compensation.”

This is his goal: removing ethnicity from the admit equation. The proposal to bias by socioeconomic status is a means to that end. Simply ending affirmative action might trigger some guilt in his reader. Saying ethnicity can or will be replaced with something that sounds fair and common-sensical defuses that reaction.

Is that its entire purpose? Would D’Souza support an actual concrete proposal for socioeconomic preferences? (Note that this, 30 years later, is still a live issue among conservatives/reactionaries. I’m unaware of anyone doing experiments, rather than rehashing arguments, but I didn’t look very hard.) D’Souza’s scorn toward Rigoberta Menchú suggests he doesn’t thrill to a poor person overcoming her background. The supposition he doesn’t really care about the genuinely disadvantaged is perhaps reinforced by a passage on pp. 56-57. D’Souza reports on a spokesperson for a group called “Chinese for Affirmative Action,” which proposes that “affirmative action should continue, and recently arrived Asian immigrants should fall under it. They are the ones most victimized.” But there would be head-to-head competition between the remaining Asians and Whites. D’Souza’s reaction is “Essentially, Yee is saying that she wants it both ways. First, give us our share of preferential treatment handouts. Once we have got our ration of protected seats, then open up the rest to open competition between whites and Asians. That way, Asians come out ahead in both categories.” D’Souza’s objection is, first, that admissions officers will still discriminate against Asians in the supposedly open competition, doing it behind closed doors because… he doesn’t say. Because that’s just the kind of people they are? But more revealing is his reaction to the first part of the proposal. Extending preferences to recently-arrived Asian immigrants is the kind of preference based on socio-economic status that D’Souza claims, two hundred pages later, to support. But here, he refers to it as “preferential treatment handouts.” (It’s ironic that, as an advocate for “treating people as individuals,” he closes this passage with an argument for group interest: “Indeed the Asian community at large might question whether it is being well represented by Der, Yee, and other defenders of criteria inimical to merit and achievement, and thus to long-range Asian interests.")

The number-like object

Let’s compare two statements from D’Souza’s third chapter, “Travels with Rigoberta,” which I analyzed here and here. The first:

The [Western Culture] requirement, established in 1980, examined fifteen great Western thinkers from a variety of perspectives or “tracks.” The courses were popular with undergraduates; a 1985 poll found that more than 75 percent considered them a “positive academic experience.” (p. 63) Note that 1985 was well before any change to the Western Culture curriculum was proposed. So the opinions weren’t affected by the controversies that came later.

The second statement is:

“A Stanford undergraduate, Lora Headrick, argued that agitation for change came from a small militant segment of faculty and students; it did not reflect broad sentiment on campus. Headrick founded a group called ‘Save the Core’ to collect petition signatures in favor of the ‘Western civ’ course.” (pp. 64-65) I’m unsure if “Western civ course” refers to one course within the curriculum or the entire multi-course curriculum. The latter seems more plausible.

How many signatures were collected for this petition? 75% of the student body? Or 10%? Just one?

Rhetorically, the second quote works to reinforce the first: the Western Culture curriculum was popular before the controversy about changing it, and it remained popular after, with the change supported by only the “small militant segment.” But all we actually know is what Ms. Headrick thought.

Even the suggestion of a number can have the power of a number.