Many years ago, I learned to fly gliders (sailplanes, airplanes but without the complicated engine bits). I learned two contradictory lessons that have stayed with me.

Don’t just do something, sit there

Since gliders don’t have engines, something has to pull them into the air. Probably the most common way is to attach a tow rope from the front of the glider to the rear of a single engine airplane. The two aircraft take off together, with the tow plane pulling the engine to, say, 2000 feet. At that point, the glider pilot releases the tow rope. The tow plane banks in one direction and heads toward the ground. The glider banks in the other direction, with its pilot hoping to catch an updraft and go higher. Here’s an image from the back seat of a two-person glider, looking out at the tow plane.

You can see that the glider appears to be somewhat higher than the tow plane. That’s intentional. The tow planes propeller produces a “wake” behind it, and you want to stay above that. There’s a certain orientation that’s most efficient.

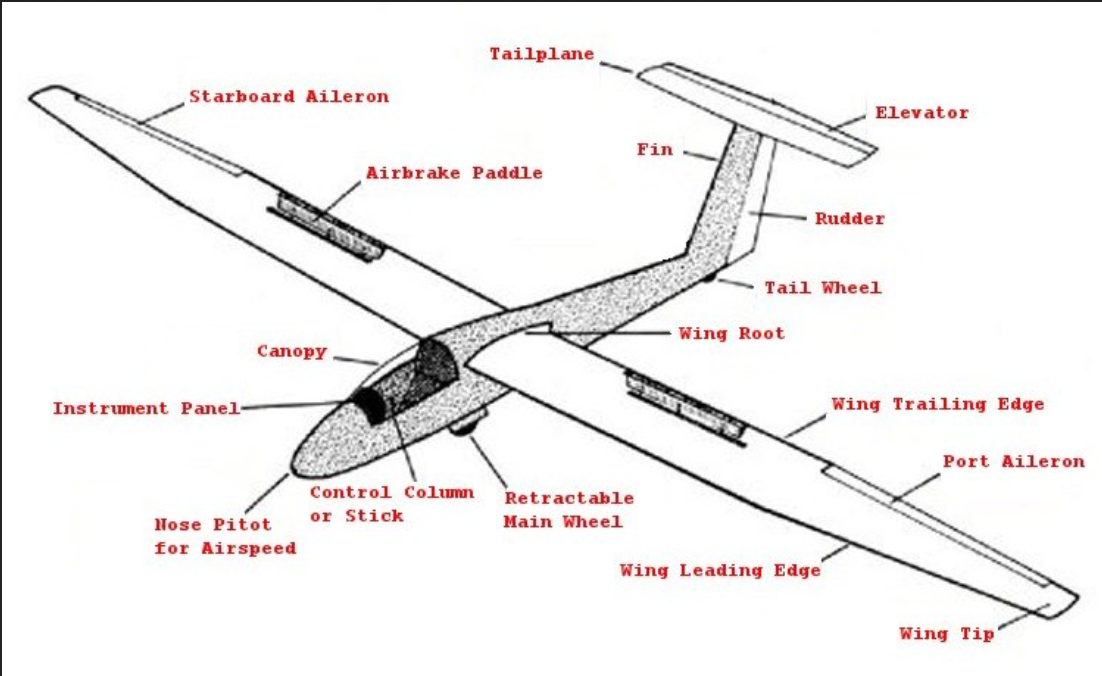

You can maintain your position by using the “stick”, which controls the elevator. That’s the horizontal bit on the tail here:

It’s hinged, so it can tilt up and down. If you tilt it up, air pressure will push the tail down and you’ll tend to go up.

Since airflow is never smooth, you need to fiddle with the stick to retain the optimal position. If you find yourself drifting up, you push the stick forward. If you are drifting down, you pull it back.

Overcorrection can be problem, especially for beginners. You’re too high, so you push the stick forward. But now you find yourself passing through the happy medium and find yourself too low. So you pull the stick back – too far – and find yourself even higher than originally. So you push…

This is referred to as “porpoising” or “pilot induced oscillation”. You’re yanking the tow plane’s tail up, then down, then up, then down. That’s not safe, so the tow plane’s pilot might release the rope on their end, leaving you to land. Here’s an example: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bAQ15b9rY94, though I’m not sure whether it was the glider or towplane pilot who released the tow rope.

Like many beginners, I was a bit prone to porpoising. My instructor (RIP) gave me this advice: “don’t just do something, sit there.” (For those who are not native English speakers, “don’t just sit there, do something!” is a much more common sentence.) If you’re out of position, you don’t have to fix it this instant. Let the situation stabilize, then g-r-a-d-u-a-l-l-y fix it.

There have been many non-aviation situations when that motto has come to mind, and I’ve done better because of it. However…

Train to act without thinking

I was taught to call out when the altimiter showed the plane passing through each of two elevations. I think they were 100 feet and 400 feet, but don’t quote me. Those two heights are relevant for how you land if the tow rope breaks.

In a normal landing, you traverse three sides of a rectangle. You start the approach by flying with the wind parallel to the runway until you’re some distance beyond its start, then make a 90 degree turn, then another 90 degree turn, then you fly into the wind to touch down. (So you land facing the same direction as when you took off.) Flying into the wind makes the landing easier because the wind is always flowing over the flight surfaces you control with the stick and rudder pedals.

You call out 400 feet because, above that height, you can make a normal landing.

Between 100 and 400 feet, you don’t have enough elevation for a normal landing, but you do have enough elevation to make a U-turn and land downwind (with the wind, in the opposite of the normal landing direction). That’s more awkward because at some point, your aircraft will be going at the same speed as the wind, meaning wiggling your flight surfaces won’t do anything. Then, as you go slower, your controls will have the opposite of their normal effect because the wind is flowing over them from the wrong direction. It’s good to be on the ground when you have to deal with all that. (In the porpoising video above, the glider pilot made a downwind landing.)

Below 100 feet, your only option is to land out. That means going forward and down and landing wherever you can. (In central USA, where I learned, glider grass strips are usually around agricultural fields, so there are lots of places to land. Many, many people land in a cornfield at least once. I wasn’t the only one!, I swear.)

You learn to fly gliders in a two-seater. The pilot (you) sits in front, the instructor behind. Both of you have the full set of controls. In particular, the instructor has a tow release knob to pull. So at least once in your training, you’ll be doing a normal ascent and suddenly the instructor will release the tow rope, simulating a rope break. Then it’s your job to land safely.

When the instructor did it to me, it was like magic. Without my having any conscious thought at all, I instantly put the aircraft into the right kind of turn for the altitude. I was rather pleased with myself.

I’ve also found this lesson useful in my career. There are cases (code smells, for example) where pausing to think is actually less useful (on average) than simply moving immediately to fix the problem.

These are contradictory mottos

Part of the trick of expertise is learning of a lot of situations, and dividing them into ones that reward sitting-and-thinking and ones that reward conditioning yourself into reflexive action.