How not to be a sucker 3: book summaries

Authors frequently refer to other books to support their argument. Readers are trained to assume the author actually read the book and is summarizing it fairly. In chapter 3 of Illiberal Education (1991), D’Souza summarized a book, the memoir I, Rigoberta Menchú: An Indian Woman in Guatemala. We can’t know whether or how much of the book he actually read, but his summary describes the book he needed for his argument, not the book Ms. Menchú produced. (I say “produced” rather than “wrote” because the book is based on 24 hours of interviews, transcribed and edited by Elisabeth Burgos-Debray.)

In this post, I’ll justify the claim of deceit and, more importantly, ask what clues could have made a reader in 1991 suspicious of D’Souza’s truthfulness.

As with all these posts, I link to archive.org’s copy of Illiberal Education so that you can check my citations. (At the moment of writing, though, the archive.org book service is still unavailable due to a cyberattack.) In quotes, words in boldface are my emphasis.

The summary

The tells

The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not “Eureka!” but “That’s funny …” – Isaac Asimov Well, probably not. As usual, Quote Investigator ruins it for everyone.

Throughout his book, D’Souza refers to people by their last name. When speaking of a professor, for example, he’ll usually introduce them with an honorific like “Professor Thomas Bergin” and thereafter refer to “Bergin.” Even when he interviews students to make them seem foolish (see a later post on how he uses interviews), he refers to them by their surname. For example, on pp. 75-76, we’re introduced to Megan Maxwell and her “clean-cut appearance”; thereafter, she is “Maxwell.”

As far as I can tell, the only exception is Rigoberta Menchú. She is introduced as “Rigoberta Menchú.” Thereafter, D’Souza frequently refers to her as “Rigoberta,” sometimes as “Rigoberta Menchú.” The chapter on the Stanford curriculum is titled “Travels With Rigoberta.“ D’Souza is fond of chapter titles that are allusions, including “The Last Shall Be First” (the Bible, Matthew 20:16), “Tyranny of the Minority” (tyranny of the majority), and “More Equal Than Others” (Orwell’s Animal Farm). Is “Travels With Rigoberta” an allusion to John Steinbeck’s Travels With Charley? I can see it: both are memoirs, and D’Souza makes much of the incongruity of a Guatemalan peasant woman having traveled to Paris (where the interviews that led to the book took place). But comparing a grown woman to a dog (Charley is a French poodle) is kind of cringe. It does fit with the belittling tactic of using the first name so much.

That’s funny…

What else is funny?

Elsewhere, Dinesh’s quotes are from the introduction, written by Elisabeth Burgos-Debray, who transcribed and translated the original interviews, and who also gets the courtesy of being referred to by her surname:

“Strangely, in the introduction to I, Rigoberta Menchú we learn from Burgos-Debray that Rigoberta ‘speaks for all the Indians of the American continent.’ This is no simple autobiography; ‘her life story is an account of contemporary history.’ Further, she represents oppressed people everywhere: ‘The voice of Rigoberta Menchu allows the defeated to speak.'” (pp. 71-72)

D’Souza then pivots from quotes (which are accurate – I checked) from the introduction to his summary of the introduction, which is that Menchú is a pawn of Burgos-Debray:

“[Rigoberta] embodies a projection of Marxist and feminist views onto South American Indian culture. As Burgos-Debray suggests in the introduction, Rigoberta’s peasant radicalism provides independent Third World corroboration of Western progressive ideologies. Thus she is really a mouthpiece for a sophisticated left-wing critique of Western society, all the more devastating because it issues not from a French scholar-activist but from a seemingly authentic Third World source.” (p. 72) Unsurprisingly, characterizing Menchú as a pawn is incorrect and disrespectful. Menchú was expelled from Guatemala for her indigenous activism in 1981 but continued it from a Catholic Bishop’s residence in Mexico, co-founding the United Republic of Guatemalan Opposition, which I presume was what brought her to Paris. She wasn’t just plucked out of nowhere by Burgos-Debray. Note that the year after Dinesh’s book, Menchú won the Nobel Peace Prize.

Google books provides enough pages that you can probably see for yourself this is bogus, but just to be sure, I bought the ebook and read it. It’s Dinesh who’s projecting. “Every accusation is a confession,” as they say.

I deeply want to describe how wrong his account of the introduction is, but this series isn’t about that sort of thing, but rather about how a reader could guess it is. (I keep having to remind myself of that, my outrage at Dinesh’s lies is so strong. Sorry.) The tell is that he shifted from quotes that are not at all about Marxism or feminism. He’s pivoted to claims without quotes. He has to, because the introduction describes Menchú as a representative of those indigenous people who, across the continent, were contemporaneously suffering (as “the defeated”) at the hands of Spanish-descended, Spanish-speaking “ladinos” (like Burgos-Debray herself, who is in fact Venezuelan, not French). Read in context, Dinesh’s chosen quotes have a very different meaning.

Dinesh can produce no quotes about feminism or feminists because those words don’t appear in the book.

Dinesh can produce no quotes about socialists or socialism because those words don’t appear in the book.

He might have used a quote about Marxism, which appears one time in the book:

“The world I live in is so evil, so bloodthirsty, that it can take my life away from one moment to the next. So the only road open to me is our struggle, the just war. The Bible taught me that. I tried to explain this to a Marxist compañera, who asked me how could I pretend to fight for revolution being a Christian. I told her that the whole truth is not found in the Bible, but neither is the whole truth in Marxism, and she had to accept that. We have to defend ourselves against our enemy but, as Christians, we must also defend our faith within the revolutionary process.”

That doesn’t fit Dinesh’s agenda.

So the tell is a shift from ambiguous, somewhat anodyne quotes, to agenda-serving claims of the Message that are not supported by quotes.

Enter self-indulgence mode

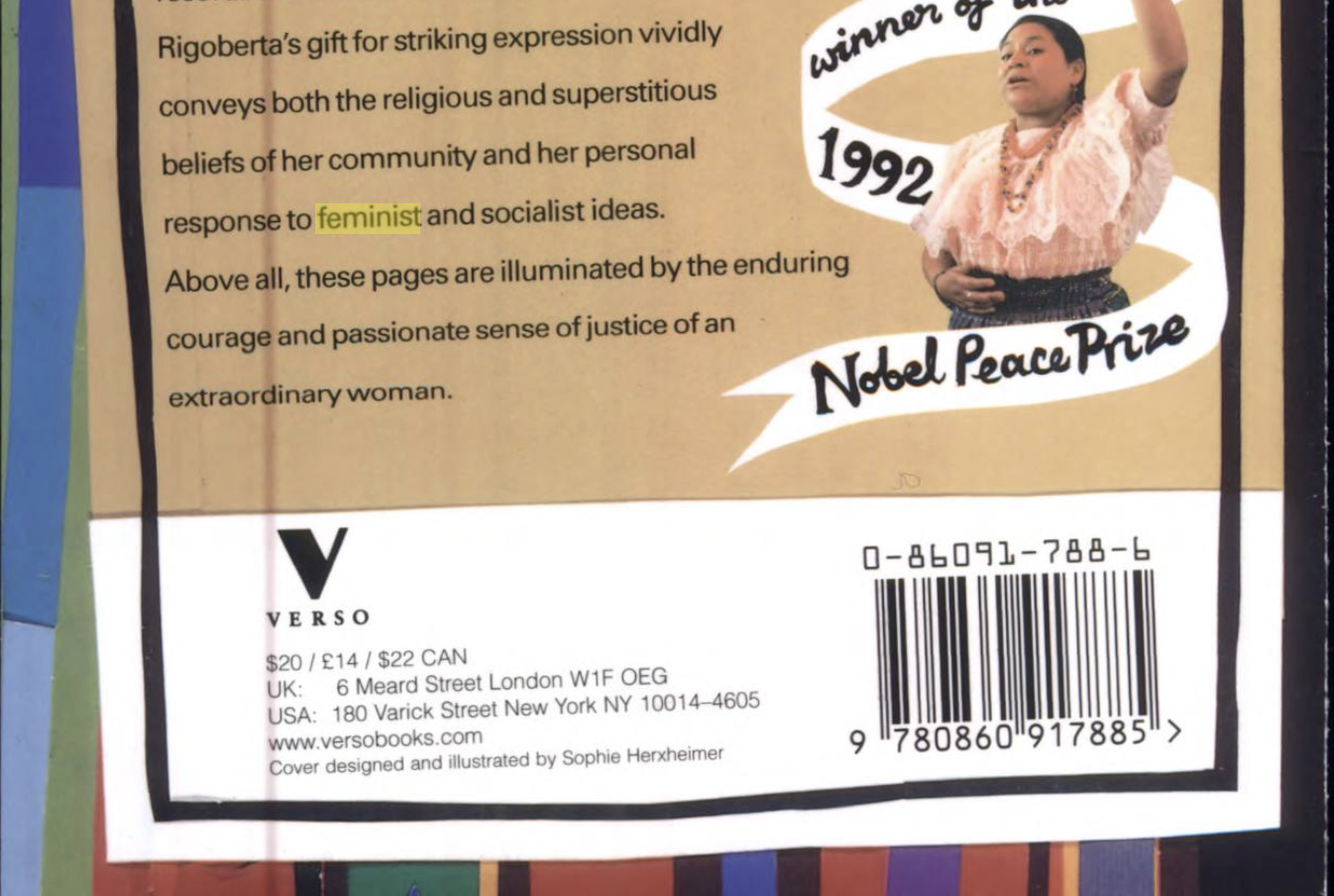

OK. I can’t resist. Before I bought the book, I was using Google Books to search in I, Rigoberta Menchú. When I searched for “feminist,” I got a hit – on the back cover of the Verso edition

It reads in part:

“Rigoberta’s gift for striking expression vividly conveys both the religious and superstitious beliefs of her community and her personal response to feminist and socialist ideas.”

It would be churlish and false of me to say that all Dinesh read of the book was the back cover – I have confirmed that all four of his quotes are present in the book – so let’s just say it may have informed his interpretation, given a predisposition to believe Rigoberta-the-dupe’s reaction must have been to embrace the ideas.

Exit self-indulgence mode

Dinesh claims Ms. Menchú is also being used as a pawn by Stanford professors:

“Her usefulness to Professor Rosaldo is that Rigoberta provides a model with whom American minority and female students can identify: they too are oppressed after all.” (ibid.)

I’m sure the “they too are oppressed” is intended to be heavily ironic. One of Dinesh’s main themes is that the Blacks and women who are being groomed to consider themselves victims actually aren’t. That’s why he opens “Travels with Rigoberta” (after two epigraphs) with:

" ‘Hey, hey, ho, ho, Western culture’s got to go,‘ The lack of capitalization is sly. What “had to go” was the curriculum named “Western Culture”; here, Dinesh encourages you to think the chant was about all of Western culture. He’s teaching the reader an attack on the first is an attack on the second. the angry students chanted on the lawn at Stanford University. They wore blue jeans, Los Angeles Lakers T-shirts, Reeboks, Oxford button downs, Vuarnet sun glasses, baseball caps, Timex and Rolex watches.” (p. 59)

Given the parallelism Rigoberta : Burgos-Debray :: Black and women students : Stanford professors, I suspect the effect on the reader of belittling Menchú is to cast students as similar dupes or pawns. (Whether that was a conscious decision, I can’t guess. Dinesh may just have reflexively belittled an illiterate peasant woman.

It might also be that Dinesh wants to further mock students by asking, “Compared to Rigoberta, you’re complaining about that?” I suspect not, as he rather downplays the violence in her life story. See below.)

I’ll generalize to note that conspiracists like Dinesh customarily divide their opponents into two categories: villains and pawns (or dupes). When you see that dichotomy pop up in a summary of a book – anywhere, really, that elides the complexity of human motivations – consider it a tell and distrust the summary more than you otherwise would.

In sum: back when I used to coach programmers, I used to counsel them to pay attention to that little nagging feeling that something’s just not right with this code. (It’s something I have to re-learn more frequently than I like to admit.) It’s the same with reading text. The chapter title, “Travels with Rigoberta,” kept bugging me. It just seemed weird. As so often happens with code, once I squelched the urge to move on, and instead investigated the feeling, I realized something I wished I’d seen immediately.

Another reason to downgrade D’Souza’s summary

(I’ll revert to his surname. The irony is played out.)

After D’Souza’s discussion of I, Rigoberta Menchú, I encountered this sentence:

“Today most of Latin America is democratic, largely due to human rights policies begun by President Carter and continued by Presidents Reagan and Bush.” (p. 87)

When I read that… well, let’s just say that if I had a hairline, my eyebrows would have disappeared into it. It’s reminiscent of Alan Greenspan’s notorious statement “With notably rare exceptions (2008, for example [aka, the Great Recession]), the global ‘invisible hand’ has created relatively stable exchange rates, interest rates, prices, and wage rates,” which led to much mockery, such as “With notably rare exceptions, Japanese nuclear reactors have been secure from earthquakes.” Among the “notably rare exceptions” for democracy in Latin America was… Guatemala, Menchú’s country, which was – at the time of D’Souza’s book – in the 31st year of a bloody civil war. (It started when Menchú was less than two years old). From Wikipedia:

[G]overnment repression led to large massacres of the peasantry and the destruction of villages, first in the departments of Izabal and Zacapa (1966–68) and in the predominantly Mayan western highlands from 1978 onward. The widespread killing of the Mayan people in the early 1980s is considered a genocide.” Recall that Menchú is Mayan. When it comes to huge numbers of deaths, D’Souza’s summary is: “Undergraduates do not read about Rigoberta because she has written a great and immortal book, or performed a great deed, or invented something useful. She simply happened to be in the right place at the right time” (p. 72) Lucky her! Not everyone gets to be a witness to atrocities.

In 1991, the 31-year-old me was politically aware enough to have been struck by the same sentence, but I doubt I’d ever heard of D’Souza. So how could I have parlayed my immediate reaction into a justified suspicion of D’Souza’s truthfulness? How, that is, could I have later read the letters column in the New York Review of Books and said, “No surprise here; his treatment of I, Rigoberta Menchú seemed dodgy when I read it.”

As noted above, D’Souza quotes nothing relevant from the actual book. What else could I have gone on? Let’s try this: since the sentence in question is about the Carter, Reagan, and Bush administrations, what was their attitude to democracy and human rights in Latin America, particularly Guatemala?

I think it’s fair to say United States’ Latin American policy throughout the Cold War (including Carter) was justified in terms of a struggle between a culture of industrial capitalism, democracy, and human rights on the one side; and industrial communism on the other, where communism-as-practiced was considered incompatible with democracy and human rights. See: the Soviet Union. Administrations held it acceptable to temporarily sacrifice democracy and human rights (for other people) because those Western virtues could be added onto industrial capitalism once it won, whereas that wouldn’t be possible if industrial communism won.

From this point of view, Brazil (whose military dictatorship ended in 1985) was a policy success, whereas Guatemala in 1991 was a success not yet achieved.

Me, reading D’Souza in 1991, would have known the Reagan and Bush administrations’ attitudes toward human rights violations in Guatemala: they didn’t happen (much) and if they did happen, it was the peasants’ fault. D’Souza discussion of Menchú echoes the party line:

-

Deflection and minimization: Menchú’s “parents are killed for unspecified reasons in a bloody massacre, reportedly carried out by the Guatemalan army” (p. 71). She is “a seemingly authentic Third World Source (p. 72) whose “victim status may be unfortunate for her personal happiness, but…” (ibid.). Contrast with Professor Woodward’s reaction after he read the book: “Her story is indeed a moving one of brutal oppression and horrors.” (Woodward, op. cit.). One cannot say D’Souza was moved.

-

They deserve it. To the Republican administrations, there were two sides. The military dictatorship was on the side of industrial capitalism, democracy (in due time), and human rights (eventually). Their opponents therefore had to be on the side of communism and dictatorship. There is no other option like, say, peasants just wanting to be left alone. By this logic, the fact that Menchú is against the dictatorship necessarily entails she is a Marxist.

Because D’Souza’s sound-bite summary of Menchú echoes the US government’s sound-bite summary about Guatemala, it’s natural to suspect it comes from the party line rather than from the text of Menchú’s book. Another reason to somewhat increase doubt in D’Souza’s credibility.

So that should dispose of this:

“Yet Burgos-Debray met Rigoberta in Paris, where presumably very few of the Third World’s poor travel. Nor does Rigoberta’s socialist and Marxist vocabulary sound typical of a Guatemalan peasant. If Rigoberta Menchú does not represent the actual peasants of Latin America, whom does she represent?”

She’s in Paris because she was invited to represent the actual peasants, which is her life’s work, and she was invited because she’s a big deal in the human rights world, you numpty! As for her